John McCain helped build a country that no longer exists

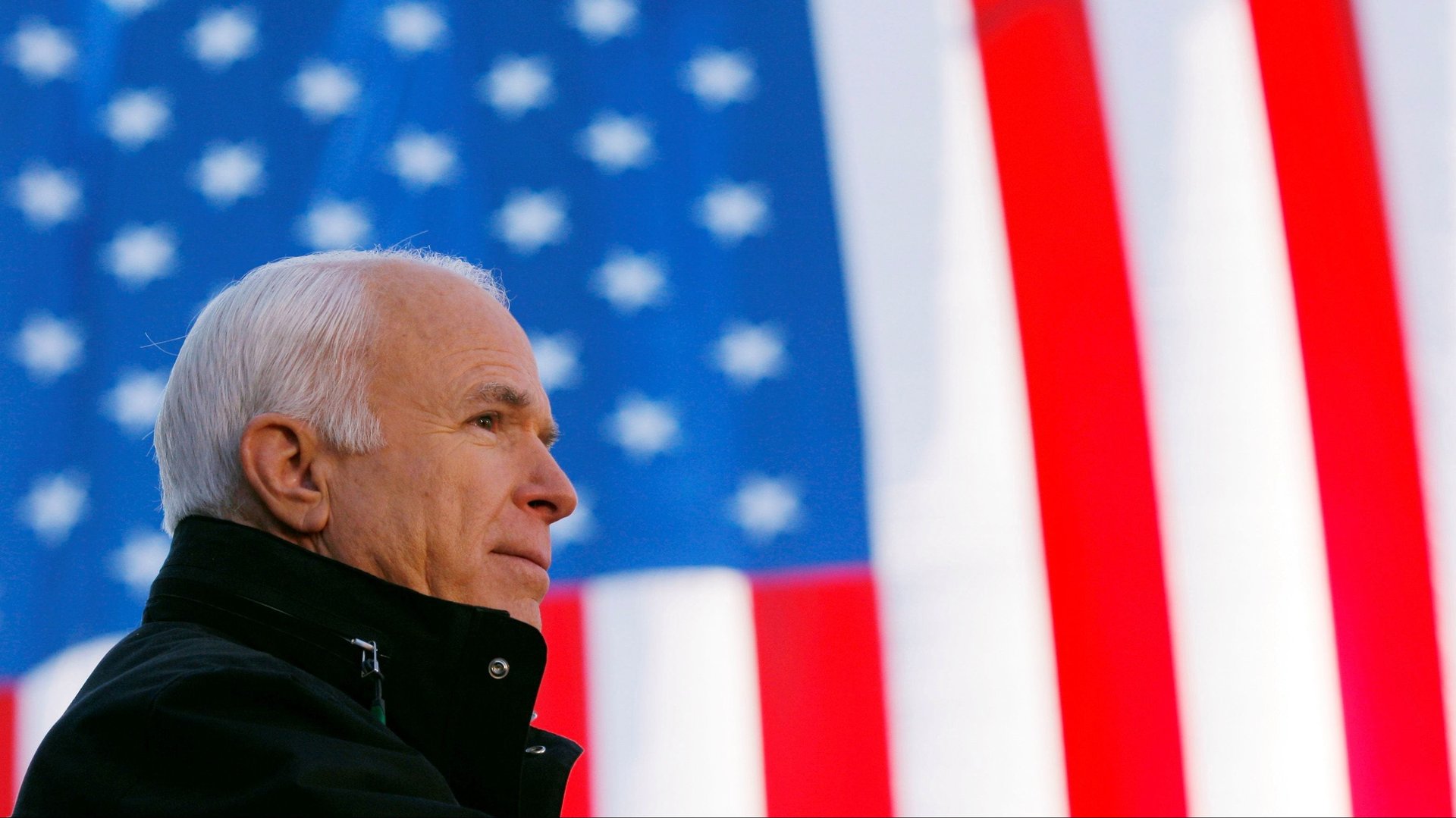

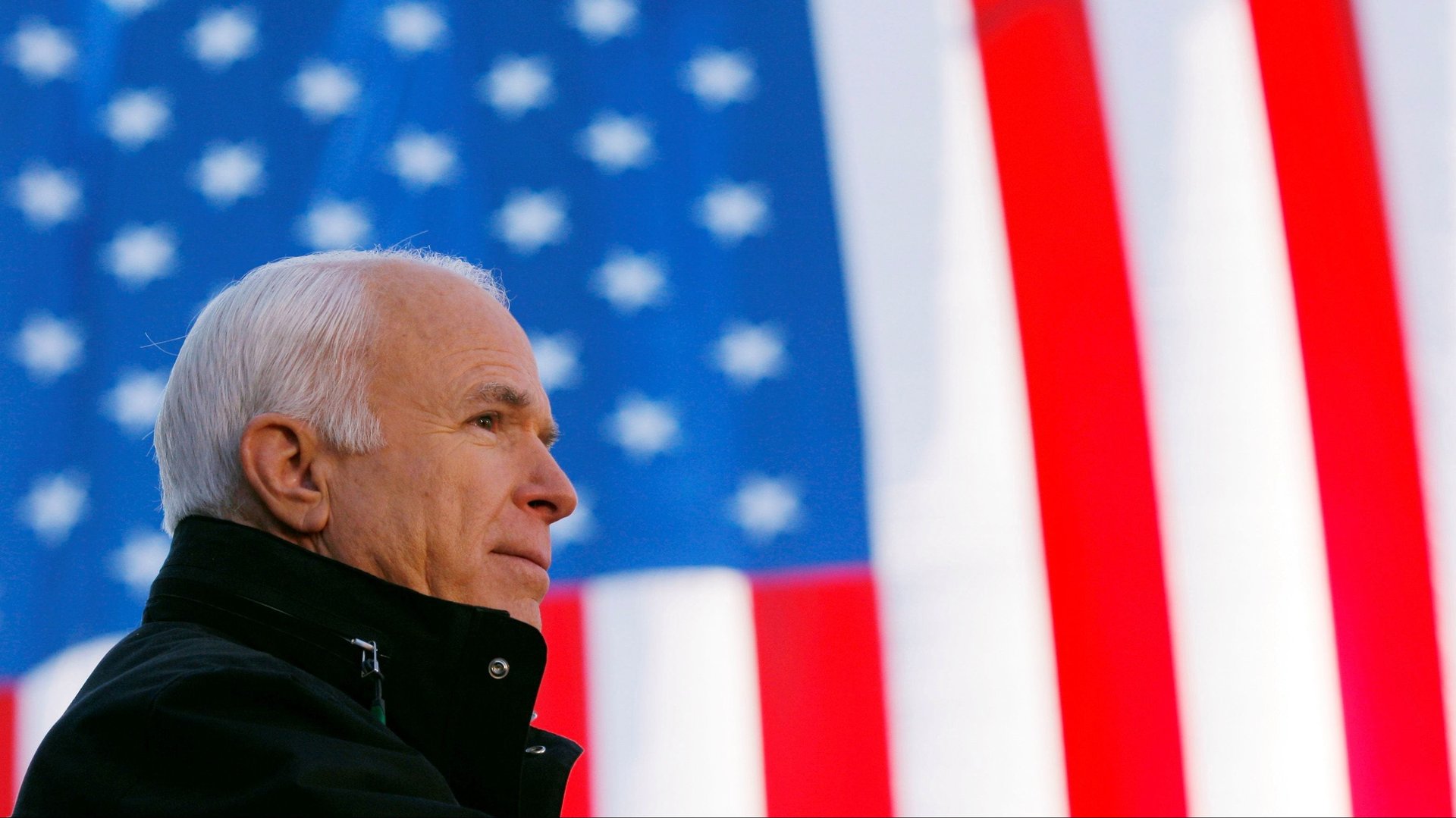

Arizona senator John McCain—scion of Navy brass, flyboy turned Vietnam war hero and tireless defender of American global leadership—died on Saturday (August 25) after a year of treatment for terminal brain cancer.

Arizona senator John McCain—scion of Navy brass, flyboy turned Vietnam war hero and tireless defender of American global leadership—died on Saturday (August 25) after a year of treatment for terminal brain cancer.

“With the Senator when he passed were his wife Cindy and their family. At his death, he had served the United States of America faithfully for sixty years,” McCain’s office said in a statement.

I am a scholar of American politics. And I believe that, regardless of his storied biography and personal charm, three powerful trends in American politics thwarted McCain’s lifelong ambition to be president. They were the rise of the Christian right, partisan polarization, and declining public support for foreign wars.

Republican McCain was a champion of bipartisan legislating, an approach that served him and the Senate well. But as political divides have grown, bipartisanship has fallen out of favor.

Most recently, McCain opposed Gina Haspel as CIA director for “her refusal to acknowledge torture’s immorality” and her role in it. Having survived brutal torture for five years as a prisoner of war, McCain maintained a resolute voice against US policies permitting so-called “enhanced interrogations.” Nevertheless, his appeals failed to rally sufficient support to slow, much less derail, her appointment.

Days later, a White House aide said McCain’s opposition to Haspel didn’t matter because “he’s dying anyway.” That disparaging remark and the refusal of the White House to condemn it revealed how deeply the president’s hostile attitude toward McCain and everything he stands for had permeated the executive office.

McCain ended his career honorably and bravely, but with hostility from the White House, marginal influence in the Republican-controlled Senate, and a public less receptive to the positions he has long embodied.

The outlier

McCain’s first run for the presidency in 2000 captured the imagination of the public and the press, whom he wryly referred to as “my base.” His self-confident “maverick” persona appealed to a more secular, moderate constituency who like him, might be constitutionally opposed to the growing political alignment between the religious right and the Republican Party.

McCain enthusiastically bucked his party and steered his “Straight Talk Express” through the GOP primaries with a no-holds-barred attack on Pat Robertson and Rev. Jerry Falwell. The two were conservative icons and leaders of the Christian Coalition and the Moral Majority.

McCain branded Robertson and Falwell “agents of intolerance” and “empire builders.” He charged that they used religion to subordinate the interests of working people. He said their religion served a business goal and accused them of shaming “our faith, our party, and our country.” That message earned McCain a primary victory in New Hampshire but his campaign capsized in South Carolina, where Republican voters launched George W. Bush, the stalwart evangelical, on his path to a presidential victory in 2000 against Democratic nominee, Vice President Al Gore.

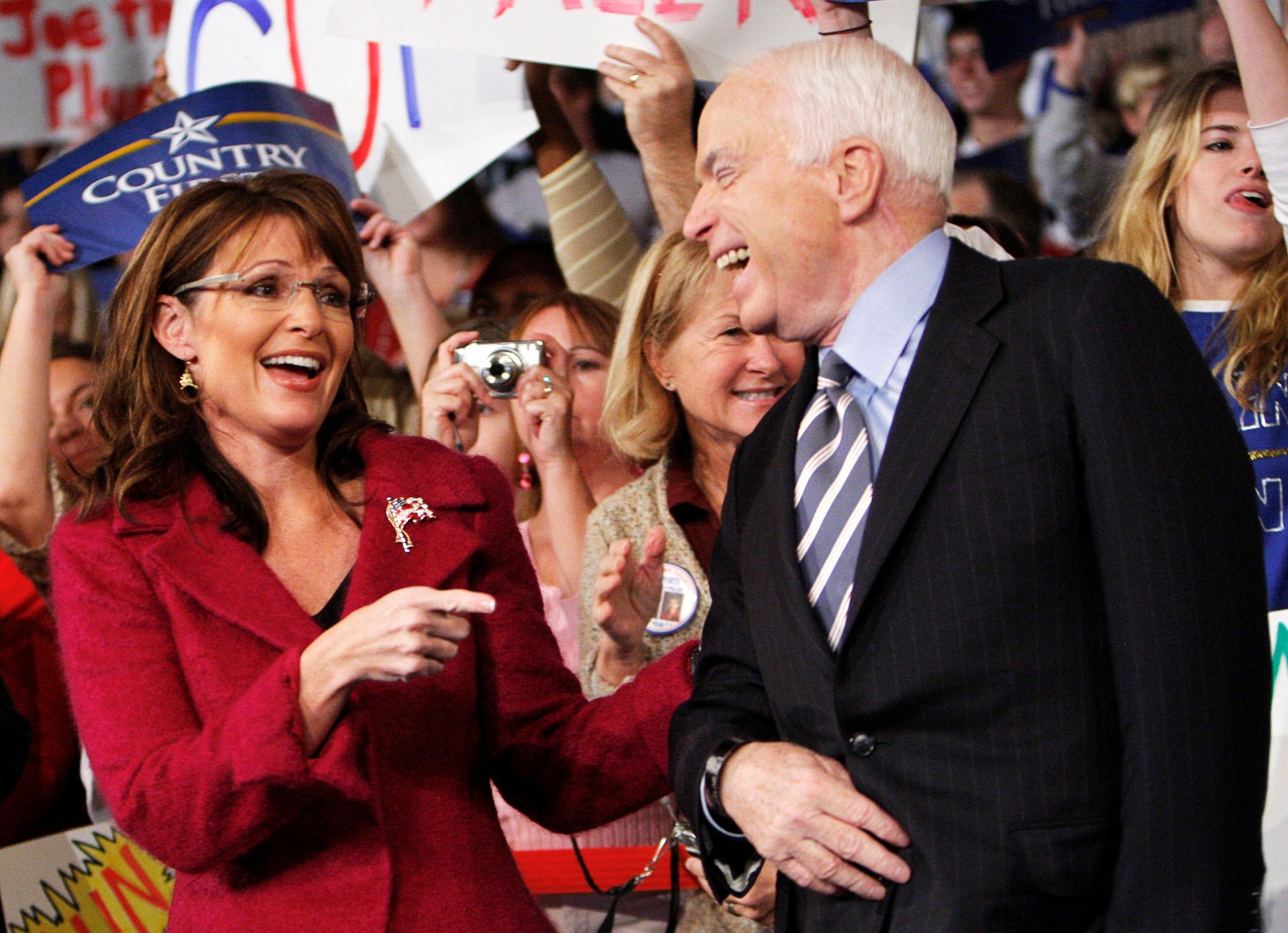

By 2008, McCain saw the political clout of white, born-again, evangelical Christians. By then, they comprised 26% of the electorate. Bowing to political winds, he adopted a more conciliatory approach.

McCain’s willingness to defend America as a “Christian nation” and his controversial choice of Alaska Governor Sarah Palin, an enthusiastic standard bearer for the Christian right, as his running mate, signaled the electoral power of a less tolerant, more absolutist “values-based” politics.

McCain’s about-face revealed a political pragmatist willing to make peace with the Christian right and accept their ability to make or break his last attempt at the presidency.

His strategy reflected his tendency to abandon principles if they threatened his quest for the presidency. Having railed eight years prior against the hypocrisy of the right-wing religious leadership, McCain may have felt some personal discomfort kowtowing to the dictates of self-appointed moral authorities. But the electorate had changed since then, and McCain showed he was willing to shift his position to accommodate their beliefs.

The primary that year also required an outright appeal to independents and even crossover Democrats. That would potentially provide enough votes to boost him past George W. Bush, whose campaign had already expressed allegiance to the conservative religious agenda.

In 2008, Mitt Romney, a devout Mormon considered religiously suspect by many evangelicals, emerged as McCain’s main rival for the nomination.

Sensing an opportunity to establish a winning coalition, McCain jettisoned his former objections to the political influence of the religious right, shifting from antagonism to accommodation. In doing so, McCain revealed his flexibility again on principles that might fatally undermine his overriding ambition—winning the presidency.

In fact, the incorporation of the religious right into the Republican Party represented but one facet of a more consequential development. That was the fiercely ideological partisan polarization that has come to dominate the political system.

The lonely Republican

Rough parity between the parties since 2000 has intensified the electoral battles for Congress and the presidency. It has supercharged the fundraising machines on both sides. And it has nullified the “regular order” of congressional hearings, debates and compromise, as party leaders scheme for policy wins.

Fueled by highly engaged activists, interest groups and donors known as “policy demanders,” partisan polarization has overwhelmed moderates in our political system. McCain was a bipartisan problem-solver and was willing to compromise with Democrats to pass campaign finance reform in 2002. He worked with the other side to normalize relations with Vietnam in 1995. And he joined with Democrats to pass immigration reform in 2017.

But he was also one of those moderates who ultimately found himself on the outside of his party.

McCain’s dramatic Senate floor thumbs-down repudiation of the Republican effort to repeal and replace Obamacare turned less on his antipathy to Trump and more on his disgust with a broken party-line legislative process.

On an issue as monumental as health care, he insisted on a return to “extensive hearings, debate, and amendment.” He endorsed the efforts of senators Lamar Alexander, a Republican, and Patty Murray, a Democrat, to craft a bipartisan solution.

Foreign and defense policy was McCain’s signature issue. He wanted a more robust posture for American global leadership, backed by a well-funded, war-ready military. But that stance lost support a decade ago following the Iraq War disaster.

McCain’s 2008 presidential campaign slogan of “Country First” signified not only the model of his personal commitment and sacrifice. It also telegraphed his belief in the need to persevere in the war on terror in general and the Iraq and Afghanistan wars in particular.

But by then, 55% of registered independents, McCain’s electoral base, had lost confidence in the prospects for a military victory. They favored bringing the troops home.

Over the course of six months that year, independent support for the Iraq war fell from 54% to 40%. Overall opposition to the troop “surge” was at 63%. Barack Obama’s promise to wind down America’s military commitment and do “nation-building at home” resonated with an electorate wearied by the conflict and buffeted by their own economic woes.

Advocate for global leadership

McCain continued to assert the primacy of American power. He decried the country’s retreat from a rules-based global order premised on American leadership and based on freedom, capitalism, human rights, and democracy.

Donald Trump stands in contrast. Trump, like Obama, promises to terminate costly commitments abroad, revoke defense and trade agreements that fail to put

In his run for the presidency, Trump asserted that American might and treasure had been squandered defending the world. Other countries, he said, took advantage of US magnanimity.

In Congress, Republicans have become cautious about US military interventions, counterinsurgency operations, and nation-building. They find scant public support for intervention in Syria’s civil war.

Seeing Russia as America’s implacable foe, McCain sponsored sanctions legislation and prodded the administration to implement them more vigorously.

Accepting the Liberty Medal in Philadelphia, McCain repudiated Trump’s approach to global leadership.

He declared, “To abandon the ideals we have advanced around the globe, to refuse the obligations of international leadership for the sake of some half-baked, spurious nationalism cooked up by people who would rather find scapegoats than solve problems is as unpatriotic as an attachment to any other tired dogma of the past that Americans consigned to the ash heap of history.”

McCain spent his life committed to principles that, tragically—at least for him—have fallen from favor, and the country’s repudiation of the principles he championed may put the nation at risk.

Editor’s note: This is an updated version of an article originally published on on June 12, 2018.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.