A 26-year-old Harry Potter fan is trying to beat Amazon in the Arab world

Ala’ Alsallal wants his online book retailer, Jamalon, to be the “Amazon of the Arab world.” Of course, the real Amazon does, too.

Ala’ Alsallal wants his online book retailer, Jamalon, to be the “Amazon of the Arab world.” Of course, the real Amazon does, too.

But the former seems to be winning, thanks to a delivery model that relies on local contacts and infrastructure. Since launching in 2010, Jamalon delivers in partnership with Aramex, a Middle East-based global transportation and logistics services company that ships in as little as three days. Jamalon also offers cash-on-delivery options to pay for its Arabic and English books, acknowledging slow credit card penetration in the region; Alsallal says roughly 85% of Jamalon’s customers use COD services.

Amazon, meanwhile, offers its English book selection to the Middle East but delivery times can range between two and four weeks. The global titan’s selection of Arabic titles is also severely limited due to the industry’s fragmentation; many publishers can’t solidify deals with the company in order to distribute their books. (Amazon didn’t return a call for comment.)

“It takes time and effort,” Alsallal says of his own strategy. “We do visit these publishers to get agreements with them.”

Against this backdrop, Jamalon sees opportunity for a niche player to develop the relationships necessary to reach consumers. An estimated 5,000 publishers in the region do not have access to Amazon or have a difficult time reaching consumers. Jordan, alone, has more than 200 publishers, and Lebanon could have upward of 1,000, says Alsallal.

Jamalon, which means “top of the pyramid” in Arabic, was founded with $12,000 in seed capital, and Alsallal’s earliest “employees” were his mother, brothers and sisters. “Once we launched, we started receiving orders and delivering them ourselves. At one stage, our marketing manager was 12 years old,” he recalls. “But we started marketing through social media and at special events as volunteers. We started advertising on Google and Facebook and reaching out to book clubs and book fairs.”

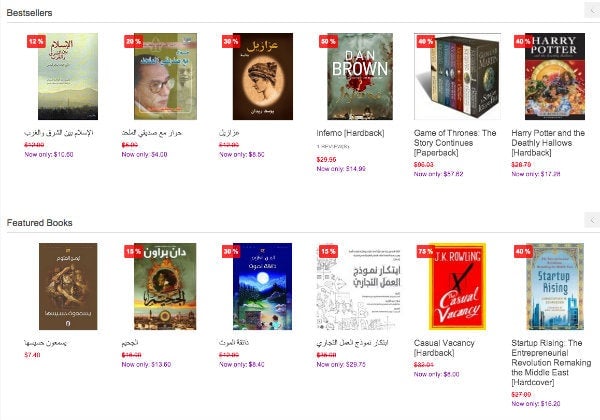

In three years, the company secured $400,000 from private Arab investors, including Fadi Ghandour, the founder of Aramex. That has helped Jamalon grow from a scrappy startup to the Middle East’s largest online book retailer offering more than 9.3 million titles. It is also the largest provider of Arabic-language books, with 150,000 titles for sale compared to a couple of hundred Arabic-language offerings by its rival Amazon.

Jamalon’s website currently boasts 400,000 unique page views a month—and a 30% monthly growth rate in sales—and the company’s physical presence has also expanded from Amman headquarters to offices in London, New York, Beirut, and Dubai. Jamalon employs 18 full-time staff and is hiring.

“More and more people are looking for digital books in the region,” says Chris Schroeder, Internet entrepreneur and author of Startup Rising: The Entrepreneurial Revolution Remaking the Middle East. “It goes back to content and navigating all of the intricacies of moving goods and services in this market.”

Alsallal would not disclose revenue figures, but says the company has yet to reach profitability. Revenue is recycled back into Jamalon to sustain growth but he is optimistic that a profit is imminent in the next two years as the company expands. By 2014, Jamalon will expand into Egypt and Morocco, and will likely add more items for sale on its website, including French-language books.

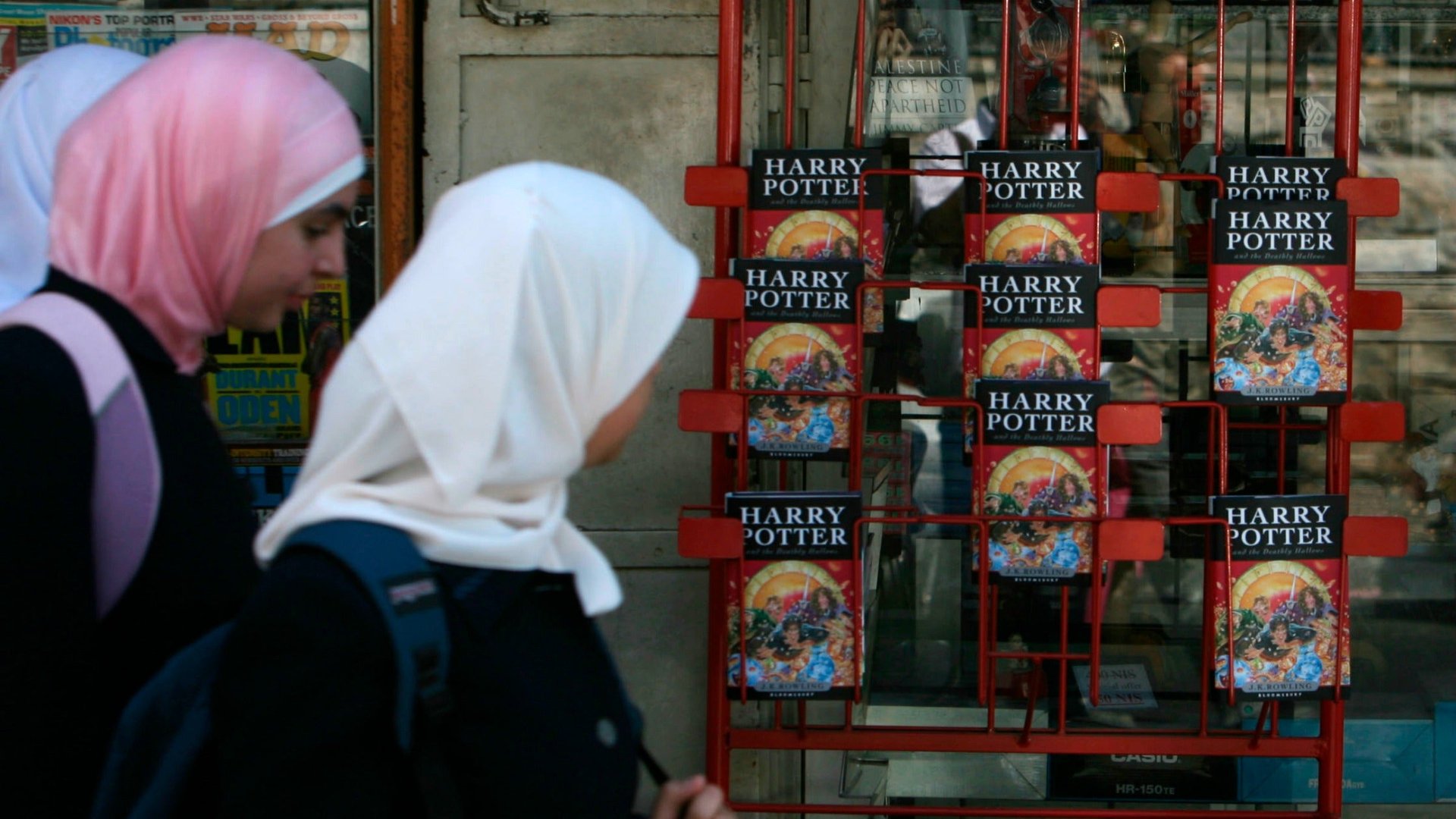

Not bad for a company that came as an inspiration after a run-in with the law. The company’s roots trace back to 2007 when Alsallal was a student in Jordan. An avid Harry Potter fan, he grew frustrated with the long delay in official Arabic translations of the novels. Alsallal gathered a group of student volunteers to translate Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, the final book in the wildly popular series.

He uploaded the translated version online and more than 1 million people downloaded it. In them, Alsallal saw a market.

J.K. Rowling’s lawyers didn’t see it that way. In 2007, they promptly served him with a cease-and-desist lawsuit in British court. To avoid legal troubles, Alsallal shut down his server. But the idea was born.

Three years later—after the death of his father, a university professor who ran a supermarket on the side—Alsallal launched Jamalon. He says he’s not as much a book publisher as a “knowledge provider.” He is eyeing innovations such as crowd publishing, which allows people to co-author books. And a Twitter post in February declared that e-books will be offered soon as well, although a timetable has not been set yet. If Jamalon is successful, such an innovation will serve as a direct dig against Amazon, which has been criticized for not making its Kindle devices capable of reading Arabic text.

Upon receiving an order, Jamalon sources from publishers and brings the products to any one of its global hubs. The hub then takes care of the packaging and preparation of the order, as well as the shipping policies and invoices. The order is ultimately shipped to its destination via Aramex, at a special rate. Thus, as a middleman in the transaction, Jamalon makes its money not through the actual front-end sale of the books but through agreements with local book publishers that allow the company to take a cut of the book’s established retail price.

A part of the challenge in the Middle East, where startups are often viewed with skepticism, is gaining trust. In an interview with Jordan Business, Alsallal said, “I have to pretend that Jamalon is larger than its size in order to even get a meeting with some publishers. Simply telling them you have several branches is a foot in the door. Otherwise, they will not take you seriously as a start-up. In other words, to be taken seriously, they have to see you as a threat.”