Seven weird food predictions from the past, including Churchill’s lab-grown chicken wings

Lava-powered steak, chicken drumsticks from a lab, and wood fungus for dinner: All these dishes were once thought of as the foodstuffs of the future. They sounded comfortingly remote at the time, but as scientific innovation revolutionizes our diets, they’ve proven to be not so distant after all.

Lava-powered steak, chicken drumsticks from a lab, and wood fungus for dinner: All these dishes were once thought of as the foodstuffs of the future. They sounded comfortingly remote at the time, but as scientific innovation revolutionizes our diets, they’ve proven to be not so distant after all.

As part of What Happens Next, our special project exploring the far-off future of the global economy, we looked at how and what the thinkers of the past thought we’d be eating today. Their predictions remind us that the future is not as certain as we think.

1893 (for 1993)

/ Liquid lunch

Before Soylent was even a blip on Silicon Valley’s radar, women’s rights activist Mary E. Lease predicted drinkable meal replacements. In an article for the Newark Daily Advocate, she forecast that little bottles of liquid “from the fertile bosom of mother earth” would take the place of ordinary meals, containing a condensed version of “the life force” found in corn, wheat, or fruit juice. (Soylent, by contrast, contains polysaccharide maltodextrin, the mineral supplement magnesium gluconate, and the industrial chemical monosodium phosphate—a little less natural.) For Lease, the drink’s principal attraction was in liberating women from the tyranny of the stove—and returning everyone the time they would have wasted masticating.

1894 (for 2000) /

Petri-dish farms

In a piece for McClure’s magazine, French chemist Marcelin Berthelot predicted that food would be produced in a lab, rather than grown in a field. “Herds of cattle, flocks of sheep, and droves of swine will cease to be bred, because beef and mutton and pork will be manufactured direct from their elements,” he wrote. But unlike in-vitro meat, which produces proteins using tissue regeneration methods, Berthelot anticipated powering this chemical meat “not by artificial combustion, but by the underlying heat of the globe.” The price of lab-made meat has come down to $37 a pound in the decade since its inception—but we haven’t figured out how to use lava to make steak quite yet.

1906 (for 2005) / Waste not, want not

Long before many acknowledged the environmental cost of farming animals, the novelist T. Baron Russell predicted as much. “Such a wasteful food as animal flesh cannot survive,” he wrote in A Hundred Years Hence: The Expectations of an Optimist. In the dawn of the new millennium, Russell wrote that people would “cease to behave as if the resources of the planet were illimitable, and could be wasted at will.” Instead, we’ve mostly done the opposite: In the period from 1900 to 2000, one British study showed that the number of sheep had increased by 500%, with cattle numbers also on the rise.

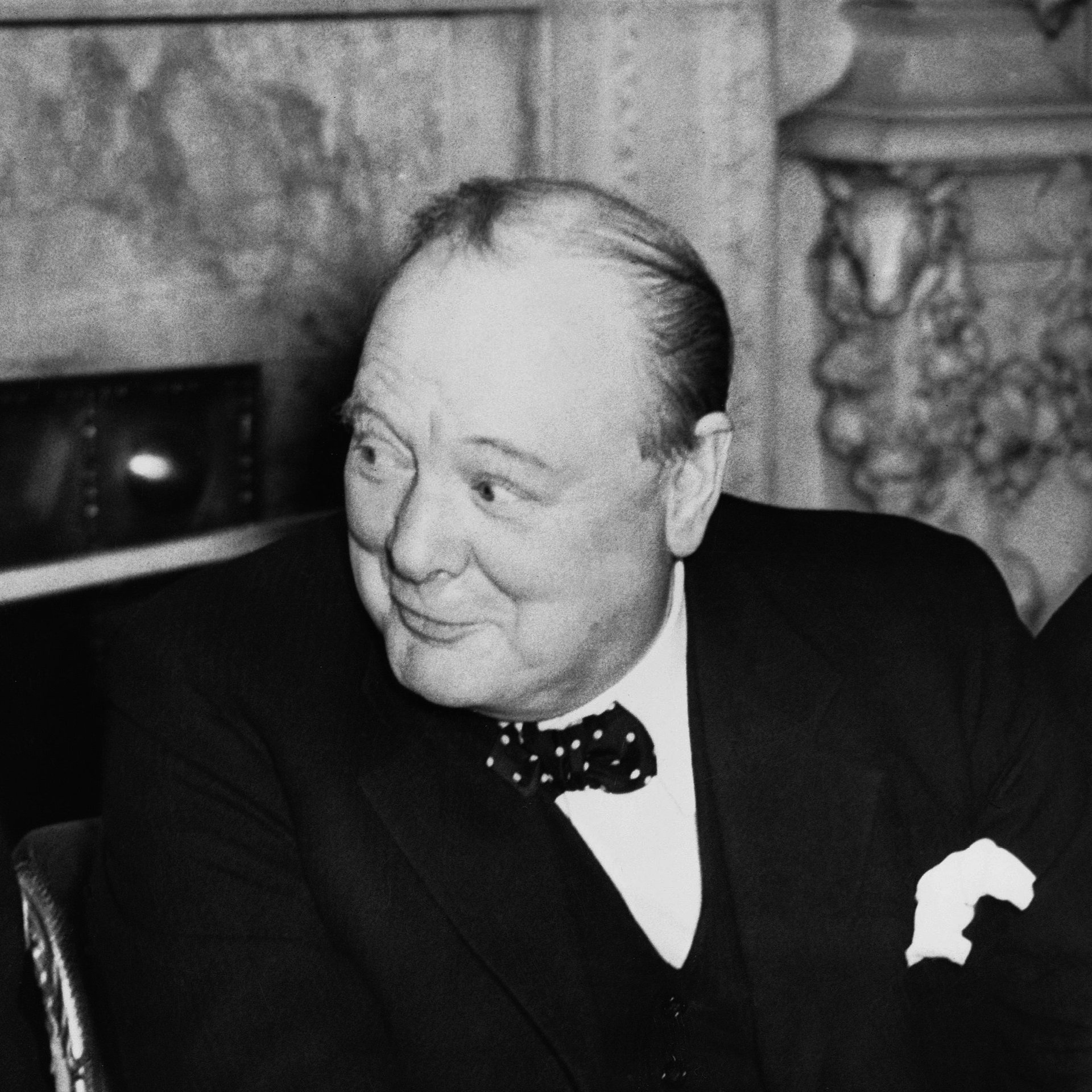

1931 (for 1981) / Lab-made chicken wings

Writing for Strand magazine, Winston Churchill envisaged a future in which scientists could grow individual chunks of meat. “We shall escape the absurdity of growing a whole chicken in order to eat the breast or wing by growing these parts separately under a suitable medium,” he wrote. The article was written five years after a British scientist first used chemistry to synthesize artificial hormones, which was the methodology Churchill thought would lead to this invention. The soon-to-be British prime minister’s timing was a little out, but his gist was correct (though we grow individual cells into meat rather than using artificial hormones).

1944 (for 2000) / Soaked in soy

When the world’s population hit 3 billion, Frederick Stare, the head of Harvard’s Department of Nutrition, said that American diets would shift away from meat and toward “skim milk, wheat and barley, soybean, and peanut products.” In some respects, he was on the right track: Soy is in almost every meal Americans eat. But the taste for animals is as great as ever, with meat consumption rates at their highest ever in the US; the average carnivore eats 222.2 pounds of red meat and poultry a year, and only 2% of people are vegetarian or vegan.

1949 / Nutritional yeast

In his treatise The Coming Age of Wood, former Food and Agriculture Organization forestry director Egon Glesinger thought “nutritional yeast”—a kind of fungus that grows on fermented sawdust—would become a building block of people’s diets. Today, vegans and healthy eaters alike swear by the stuff, using it to thicken soups, add flavor to tofu or popcorn, or as a replacement for grated cheese, though it hasn’t become the “economical and speedy solution” Glesinger proposed “to the world’s main nutritional problem, the deficiency of animal products in the diet.” Worldwide, over 800 million people are undernourished, with many experiencing vitamin A and zinc deficiencies.

1955 / Single-serve cows

In the mid-20th century, a writer for Science Digest predicted that “beef cattle the size of dogs will be grazed in the average man’s backyard, eating especially-thick grass and producing specially-tender steaks.” Thanks to the power of radiation, these mini cows would be the perfect size for a single family to eat, bringing bespoke beef literally to one’s doorstep.

1975 (for 1995) / Six-legged protein

Pioneering entomophagist Victor Benno Meyer-Rochow predicted that insects might have a role to play in global nutrition. The most delicious specimens would be hand-caught or collected out in the fields, while others could be commercially farmed and then sold “cooked and canned, dried or pickled, fresh or in the form of insect-meal.” (Serving suggestions include “roasted locusts with woodlice sauce.”) Currently, crickets have caught the attention of adventurous eaters: Helped by the fact that they have more than double the amount of protein of beef by weight, edible insects have been proposed as a solution to global malnutrition.

What do the experts of today think the food of tomorrow will look like? Read some current predictions about the Future of Food.