An algorithm is learning to detect whether patients will wake from a coma

In a hospital in China, human doctors diagnosed a number of patients in a vegetative state as unlikely to ever wake up—but a second opinion from an algorithm said they would recover in less than a year. In seven cases, the algorithm was right.

In a hospital in China, human doctors diagnosed a number of patients in a vegetative state as unlikely to ever wake up—but a second opinion from an algorithm said they would recover in less than a year. In seven cases, the algorithm was right.

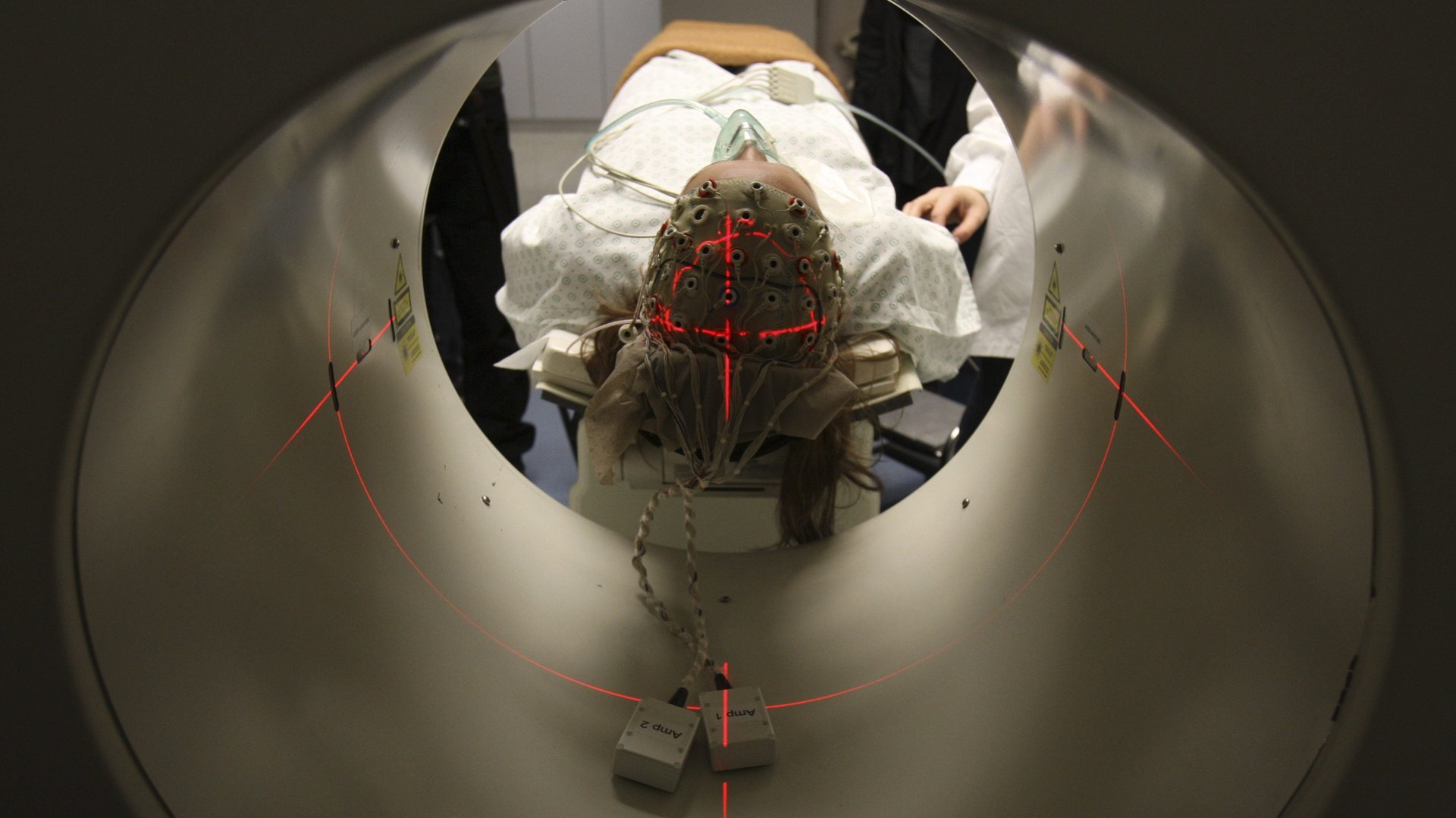

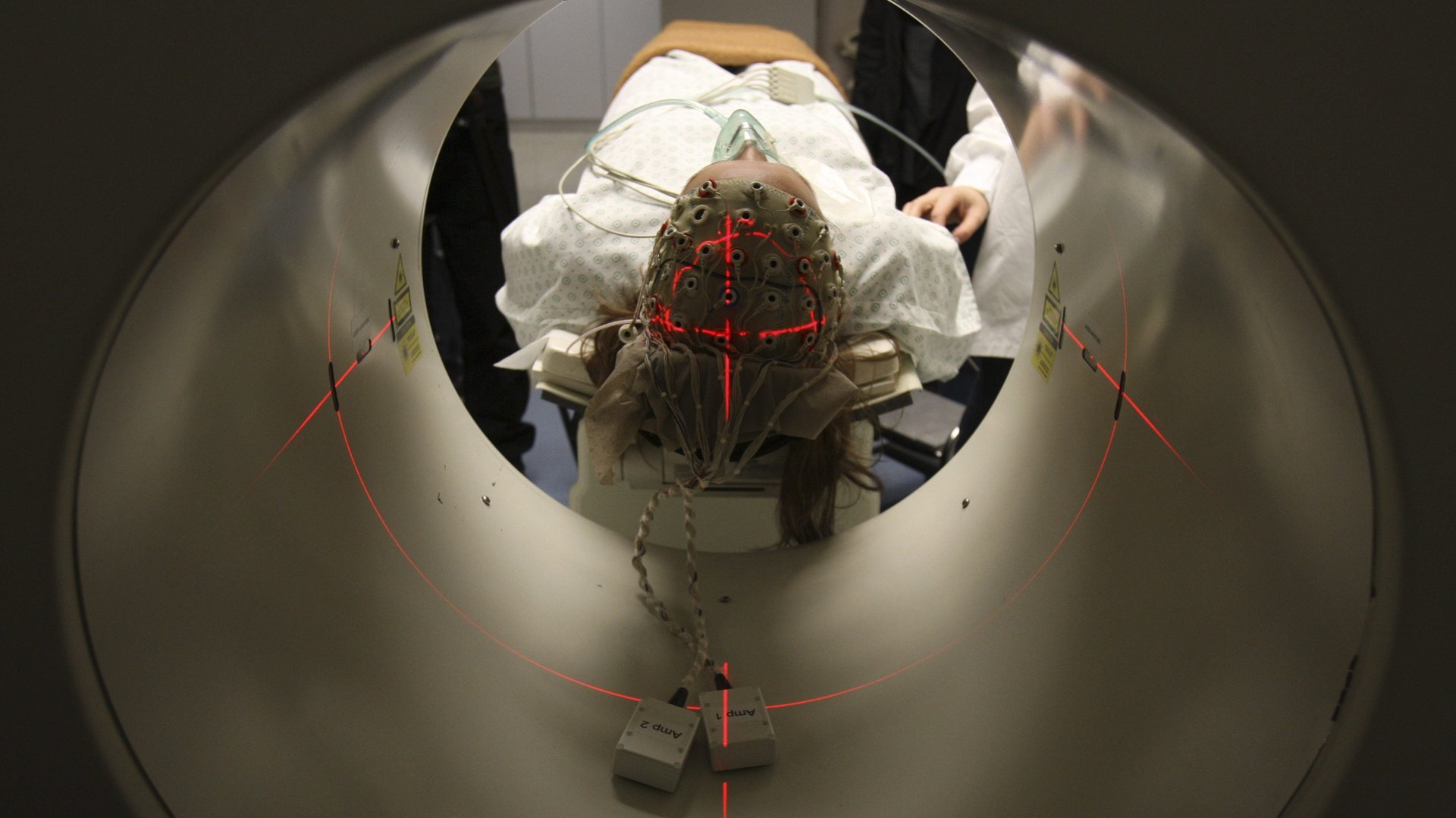

The AI algorithm, developed by the Chinese Academy of Sciences and PLA General Hospital in Beijing, analyzes fMRI scans of a patient’s brains to gauge how blood flows to different areas of the brain, as well as information given by doctors like the patient’s age, how long they’ve lost consciousness, and the cause of the coma, and then makes its diagnosis. The algorithm and research underlying it were announced in the journal eLife in August 2018.

Earlier this month, the researchers from the two Beijing-based organizations told the South China Morning Post that the algorithm has now been used to evaluate more than 300 people, and has in many ways proven its value as an additional tool for making hard medical decisions.

When the patients’ families were told the algorithm’s scoring, the patients’ doctors said not to base their entire decision to continue life support on the algorithm’s assessment. That’s because the algorithm isn’t right every time. (For example, a 36-year-old man who was scored to not recover by both doctor and algorithm ended up making a full recovery within a year.) Plus, the algorithm can only predict what’s happening inside the patient’s brain, meaning it couldn’t account outside factors like, say, a disease caught from another patient in the hospital. (Of course, a doctor wouldn’t be able to predict that either.)

The algorithm was developed over the course of eight years, and trained on scans of 160 patients with consciousness disorders, meaning they were either in a vegetative state or minimally conscious. While this dataset is small compared to the hundreds of thousands of images typically used to train other image-based AI algorithms, the researchers claim the system is 88% accurate at predicting whether a patient would recover within a year.

Data analyzed by the algorithm came from two medical centers, which proved to have different kinds of patients, says co-author Tianzi Jiang. For instance, in one medical center there were more stroke patients, while the other had more patients in a coma from lack of oxygen. In addition, differences in the kind of scanner used and imaging protocols created variations in the the two sets of data. Despite those disparities, the algorithm was able to achieve 88% accuracy in prediction when tested on both data sets.

The researchers aren’t yet sharing results on how accurate the algorithm has been in the real world, but are now working to collect more data, Jiang says.