US companies’ love affair with tax havens could help solve a long-running economic mystery

There’s something special about the United States: It earns very high returns on foreign investments, despite being the world’s largest net borrower.

There’s something special about the United States: It earns very high returns on foreign investments, despite being the world’s largest net borrower.

That means that Americans, en masse, are borrowing money from foreign countries to re-invest in those same foreign countries, and profiting handsomely on the deal. That sort of arbitrage shouldn’t persist: How does the US get away with it?

A new working paper by economists Gabriel Zucman and Thomas Wright suggests that a major factor is American companies shifting their profits to tax havens. This, they argue, can explain half of the excess returns recorded since 1966; US investors earn about 4.5% more on their foreign direct investments than foreign investors in the US do.

This “exorbitant privilege” is often pinned to the dollar’s role as the world’s reserve currency, but many debate how much benefit is truly tied to the almighty dollar. The new data suggest that the hidden realities of global capital flows help explain this longstanding economic puzzle. More clarity was made possible by last year’s tax reform law, which cleared the way for American companies to avoid paying most US taxes on foreign profits.

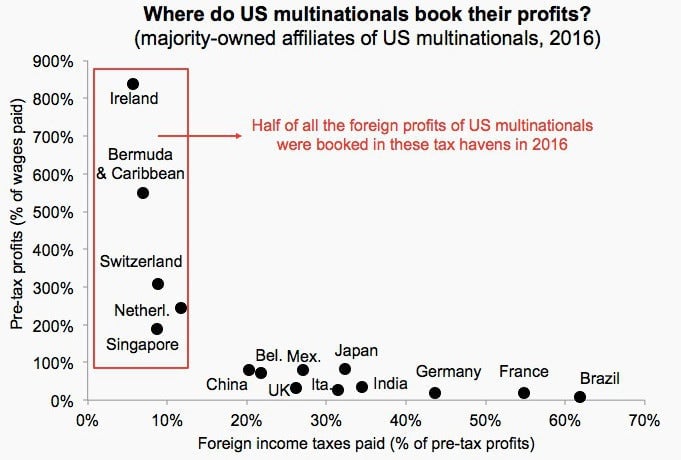

Wright and Zucman look at two factors to explain why the privilege exists: The tax treatment of the foreign subsidiaries of US oil companies, which comprise a historically large share of US corporations’ foreign income, and the treatment of subsidiaries in foreign tax havens, which now make up more than 50% of total after-tax profits booked by US companies.

The economists observe that since the Gulf War, US oil companies have seen their foreign tax rates average 45%—a number that, by falling just below the statutory rate in the US, allows countries hosting US drillers to maximize their own return while eliminating potential liabilities for the company back home.

The authors calculate that if those countries had set a tax rate designed simply to maximize revenue to the point where oil firms earned returns comparable to other industries, it would reduce the US advantage in foreign earnings between 1966 and 2016 by 20%.

The rest of the difference comes from the ability of companies to shift their foreign (and sometimes domestic) profits to tax havens abroad. In the first half of the 1990s, multinationals paid a 35% tax on their profits in foreign countries, but that has plunged to about 20%. Until last year, most tax on US profits abroad was deferred by companies. The 2017 tax bill signed by president Donald Trump set a minimum rate on foreign earnings, formally recognizing that the US won’t tax foreign profits.

In 2016, the most recent year for which we have data, half of US foreign profits were booked in tax havens. This is part of a broad trend of US companies moving profits to havens that began in the 1980s.

The economists make a counter-factual calculation that, if US corporations couldn’t shift profits to tax havens and were forced to pay the normal US corporate tax rates on their foreign profits (less credits for taxes paid abroad) it would reduce the US investment advantage by 1.2 percentage points, on average.

All told, “oil and tax avoidance by non-oil multinationals” account for half of the 4.5-point excess investment return earned by US companies over the past 50 years, the researchers conclude. The rest, perhaps, can be explained by factors including currency, culture, and corruption.

This dataset improves to our understanding of inequality, revealing the ways that US corporate profits can soar without the country’s tax take rising in tandem. It suggests that the combination of dollar power and the US tax code doesn’t privilege America at the expense of foreign rivals, but American shareholders at the expense of their fellow citizens.