Our communication is being increasingly limited to emojis

Do you ❤️❤️❤️ wedding pics? 🤤 at homemade pasta?

Do you ❤️❤️❤️ wedding pics? 🤤 at homemade pasta?

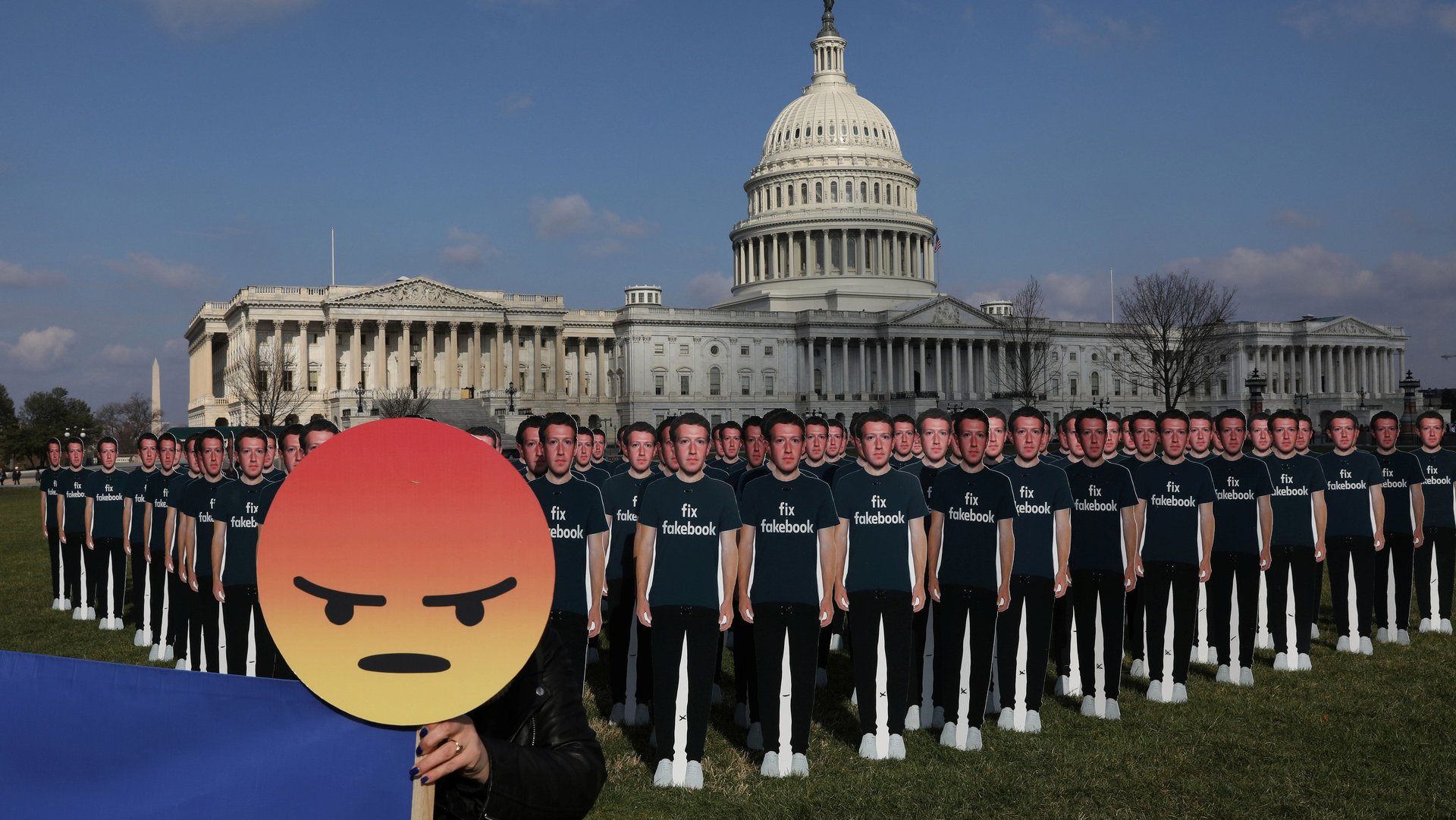

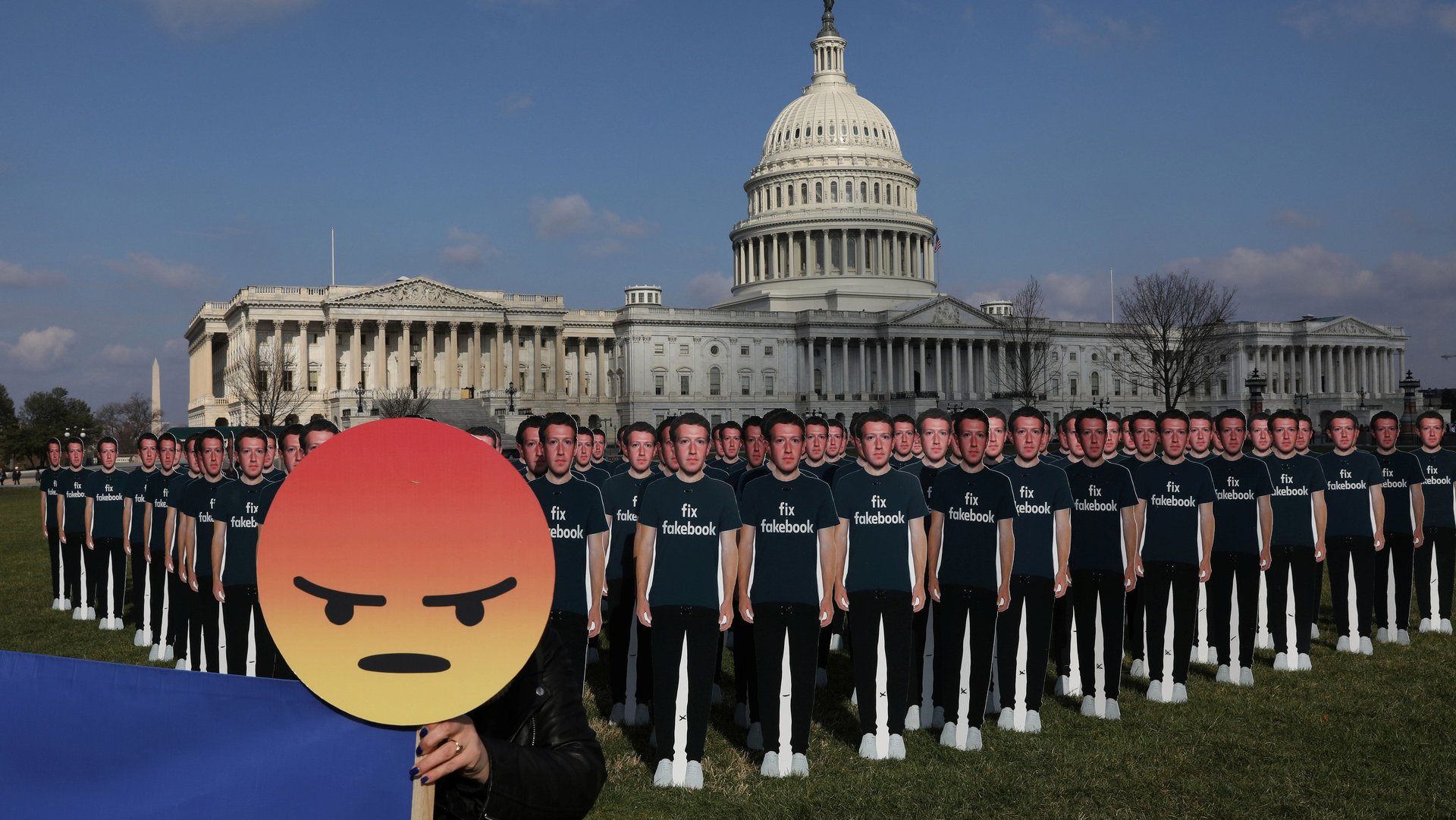

Last week, Instagram became the latest tech company to emphasize responding via emoji. The app now prominently displays a repertoire of your preferred emoji above the text box to comment on a post. After all, why express yourself in words, when you can just 😍 or 👸?

Instagram is hardly alone: In 2016, Apple and Facebook both introduced features that make reacting with an emoji the easiest way to respond. Facebook gives you six different reaction buttons under every post or comment: a like, a heart, a laughing face, a shocked face, a sad face, and an angry face. Meanwhile, iMessage “tapbacks” let you emoji-react to an individual text if you press down on the message for a couple of seconds; these are a variation on the same theme: a heart, a thumbs up, a thumbs down, a “ha ha”, an emphasis (!!), and a question mark.

According to Pamela Pavliscak, a digital anthropologist who specializes in our emotional relationship with technology, limiting reactions to these emotions, as Facebook and iMessage do, stems from established theories in evolutionary psychology. These can be traced all the way back to Charles Darwin, but were developed in the 1960s by psychologist Paul Ekman. Ekman identified six core emotions—joy, surprise, sadness, anger, disgust and fear—and said that their corresponding facial expressions were universal. (He later added more emotions.)

That’s just one theory of emotions; Pavliscak says other theories argue that human emotions are more complex, as well as more “cultural, social and personal, based on your memories and perceptions.” The academic debate about the universality of human emotions is heated.

But there’s no arguing that the original six are easy to recognize and group, especially by machines. That makes them valuable for companies. On Facebook, for example, advertisers have insight into how Facebook users “reacted” to their ads, which they can then use to inform future campaigns.

Pictogram communication can be both delightful and useful, especially in the digital era. Emojis often clarify the tone of an otherwise cryptic text or chat, and a laughing yellow face with tears bursting out of its eyes is just as effective as a “hahahah,” but pithier and more fun. Conversing without words, however, can also be confusing: A texter is left to interpret what their friend meant by !!-ing an iMessage about plans for the evening.

Pavliscak warns that compressing the array of emotional reactions available to us flattens out the way we talk to each other. ”We forget that there are other dimensions to emotions that are really important to the way we communicate and establish relationships and our identities,” she says.

When it comes to emotional intelligence, Pavliscak says, the more concepts you have, the more distinctions you can make, and the more coping strategies you can develop. By contrast, limiting the number of emotional reactions might change how we understand feelings in the future. With fewer fine distinctions, emotions could get more extreme.