The long, strange journey of a Renoir painting stolen by the Nazis

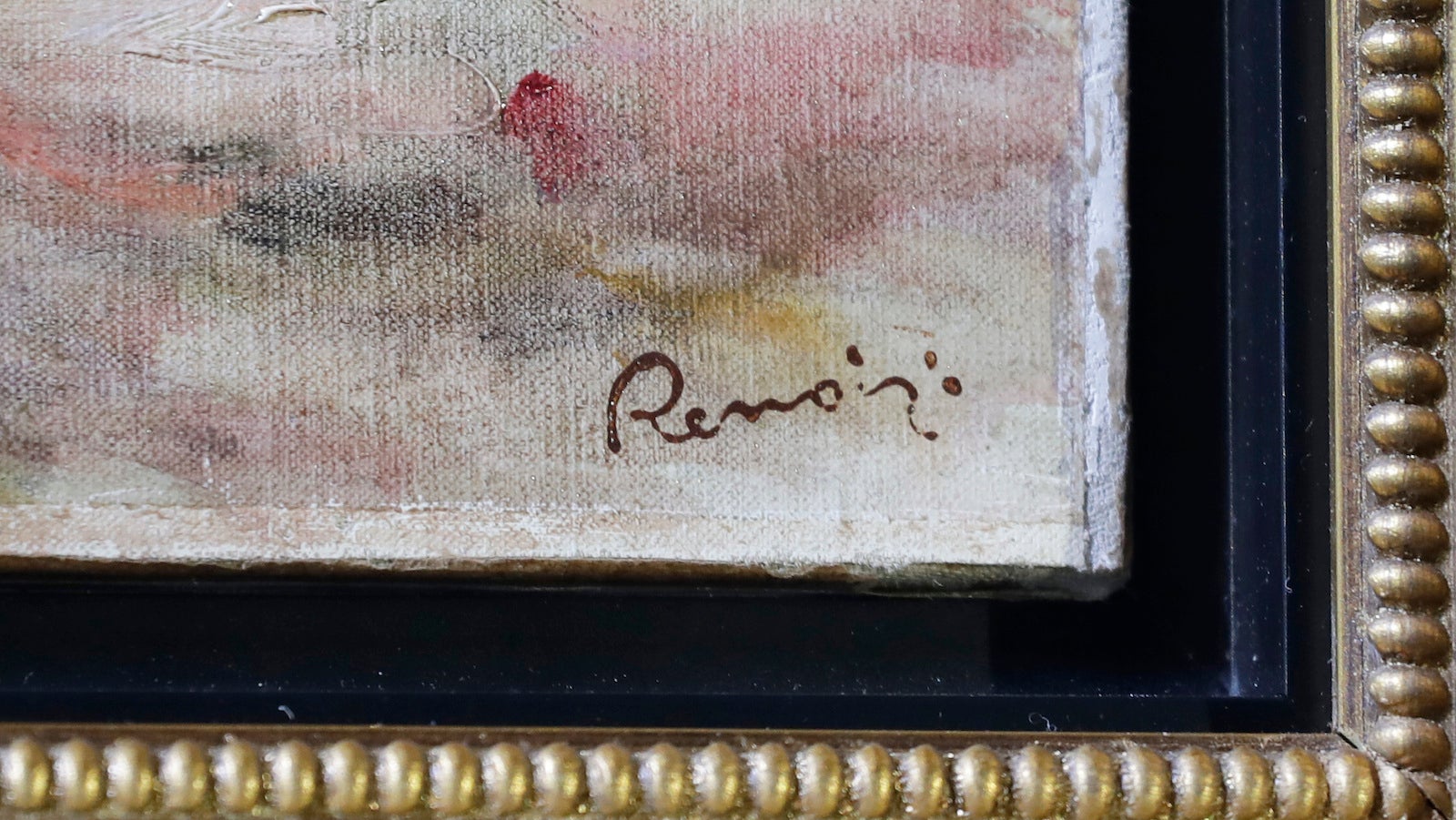

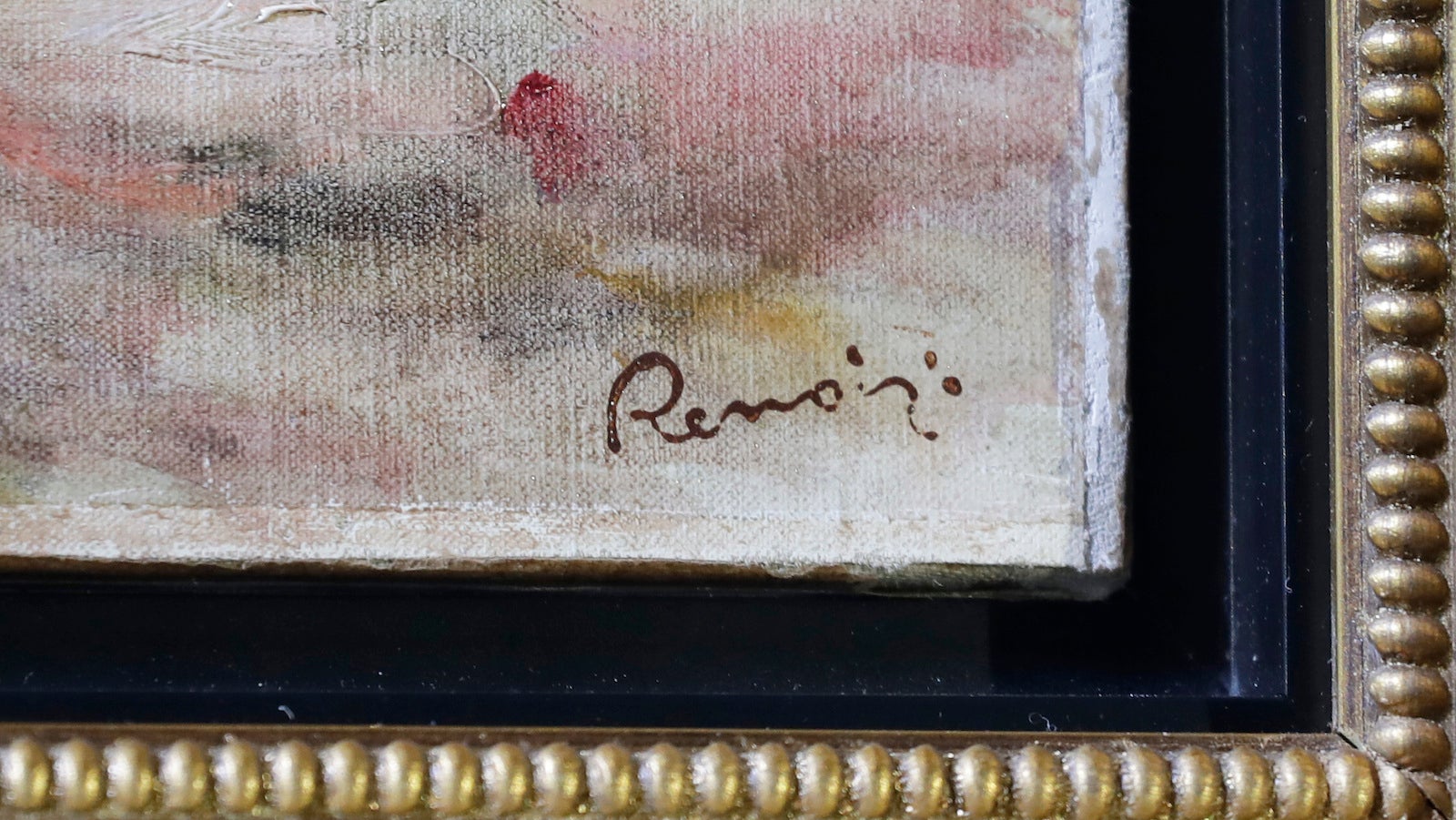

When Alfred and Marie Weinberger fled the Nazi occupation of Paris at the height of World War II, they left behind 13 paintings in a bank vault. These included a work by Eugene Delacroix and several by the Impressionist master Pierre-Auguste Renoir, including one of his last works, “Deux Femmes Dans Un Jardin,” purchased in 1925. It dates from 1919, one of Renoir’s last paintings, made at a time when his arthritis was so bad that he could hardly hold onto his paintbrush.

When Alfred and Marie Weinberger fled the Nazi occupation of Paris at the height of World War II, they left behind 13 paintings in a bank vault. These included a work by Eugene Delacroix and several by the Impressionist master Pierre-Auguste Renoir, including one of his last works, “Deux Femmes Dans Un Jardin,” purchased in 1925. It dates from 1919, one of Renoir’s last paintings, made at a time when his arthritis was so bad that he could hardly hold onto his paintbrush.

On Dec. 4, 1941, the Nazis seized all the paintings, including “Deux Femmes.” In 1942, the painting was handed over to the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR), a Nazi task force headed by leading ideologue Alfred Rosenberg dedicated to stealing cultural artifacts of the regime’s enemies.

Though the Weinbergers were able to get six of their artworks back after WWII ended, it seemed as if “Deux Femmes” had disappeared amid the fog of war. Alfred Weinberger registered claims to the Renoir with the French authorities in 1947 and the German authorities in 1958 but he would never see it again.

The Renoir reappeared in Johannesburg, South Africa in 1975, then it was sold at auction in London in 1977—the same year that Alfred Weinberger died just shy of 90 years old. It was offered for sale at Christie’s auction in 1996, where it went unsold, and then again in 1997. The Renoir eventually resurfaced at a sale in Zurich, Switzerland in 1999, according to the US attorney’s office of the southern district of New York.

The painting next appeared at a Sotheby’s auction in New York in 2005, according to the New York Times (paywall), where it sold for $180,000 to the Park West Gallery, which runs art galleries on cruise ships. It was put back for sale in 2009, but it did not sell until 2012, when Park West sold it for $390,000.

In 2013, “Deux Femmes” appeared for sale at a Christie’s auction in New York. By this point, Weinberger’s granddaughter, Sylvie Sulitzer, had been alerted of the painting’s existence—and her grandfather’s claim to it—thanks to the work of a German lawyer who’d gotten in touch in 2010 after having gone through the ERR’s meticulous records. She made her claim, and the painting’s unnamed owner voluntarily relinquished the painting.

The painting was finally and officially handed back to her yesterday in New York, where it is currently on display at the Museum of Jewish Heritage. For most of her childhood, Sulitzer didn’t even know about the paintings. “As far as I can remember, nobody ever spoke about the war,” she said. “It was taboo.”

The journey of the Renoir painting will not end there, though. After being separated from the painting for 77 years, Weinberger’s family will only be the owner of the painting for a couple of months. Sulitzer plans to sell it at auction at Christie’s in New York on Nov. 12—to pay back the French government for compensation she had previously received for her lost paintings. “I would have loved to keep it,” she said.

There could yet be more of this story to come. From the Weinbergers’ small pre-war collection, there are still four more Renoirs and the Delacroix that remain missing.