The scariest thing about China’s latest cash crunch is we don’t know if there is one

Money market rates opened at a four-month high in China today, triggering some unpleasant flashbacks of the cash crunch that jarred markets for a week or so in June. What’s going on?

Money market rates opened at a four-month high in China today, triggering some unpleasant flashbacks of the cash crunch that jarred markets for a week or so in June. What’s going on?

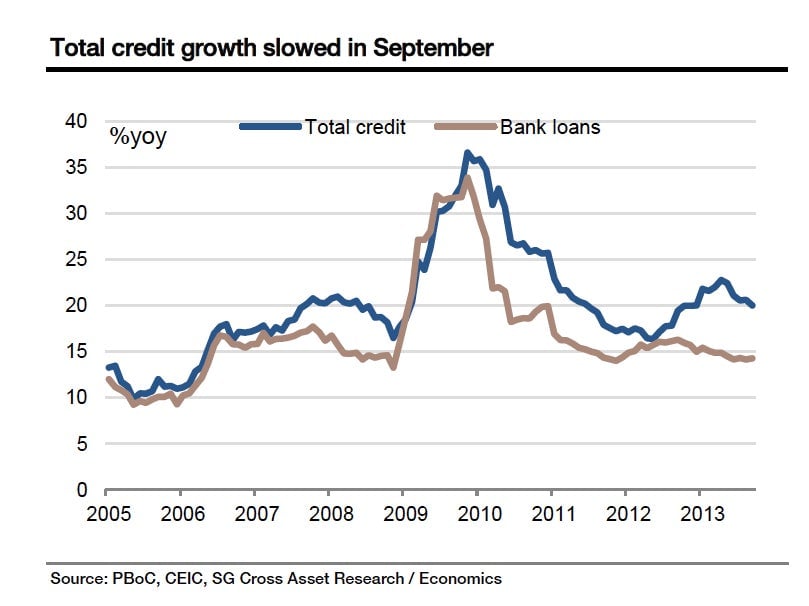

The handiest answer available is probably that the central bank is “tightening.” The People’s Bank of China (PBOC) is declining to inject liquidity into the system, draining off 58 billion yuan ($9.5 billion) this week. That’s not much money in the grand scheme of things—particularly when total credit is growing 20% annually. But liquidity grows scarcer at month’s end when banks scramble to round up enough cash to meet reserve ratio requirements.

Meanwhile the competing theory is that cash froze up after Bloomberg announced that China’s five big state-owned banks wrote down $3.65 billion in bad debt in the first six months of 2013, nearly three times more than in 2012’s first half. That might be alarming to Western investors, but it can’t have been shocking to anyone in China.

The weirder thing is probably that rates haven’t jumped sooner. That’s because the government is trying to rein in credit growth without causing lending to freeze up. But the economy is no less reliant on its need for credit to paper over bad investments than it was in June. It’s a condition that Patrick Chovanec, chief strategist at Silvercrest Asset Management, likens to having chronic high blood pressure.

“In June [the economy] had a heart attack… They stabilized the patient, but the disease that caused the heart attack hasn’t gone away,” he tells Quartz. “Maybe you are monitoring the patient carefully, but the patient still has heart disease.”

Monitoring the patient is hard, though, given how opaque the Chinese financial system is. When the government thinks it has closed one credit channel, another one has opened somewhere else, for instance in private equity financing that no one is reliably tracking.

So what might prompt another heart attack? It’s impossible to guess. For several good reasons, many dicey scenarios could have unfolded in September. But big investment inflows probably saved the day. David Cui of BofA/Merrill Lynch argues that the trigger of another panic could come when China’s shadow banking sector—meaning the lending made off bank balance sheets—”realiz[es] how much risk it’s taken on” and refuses “to provide the necessary credit.” Among the possible triggers, says Cui, are a drop in housing prices, default of a local government financing vehicle (LGFV) trust or the government’s announcement of local government debt levels, expected in November.

There’s also the possibility that the PBOC will manage to bring down credit growth without prompting a rash of defaults and a bank panic. Wei Yao of Société Générale has been making the case that deleveraging is underway, which is a good sign. But the reason credit demand is still strong is worrying: It’s coming from insolvent parts of the economy, such as LGFVs. No one really knows how deep in the hole they are. Unfortunately, that includes the PBOC, as June proved. Has that changed, though? Not really, says Chovanec.

“It’s not that they don’t have a clue, but I’d compare it to global financial crisis where it took a while for [the US government] to even figure out what the state of these financial companies was,” he says. “It’s the lack of visibility that makes it challenging… if you pulled this thread, what will it unravel?”