The story of segregation in Los Angeles was only preserved by its black-owned papers

The historic segregation that defines Los Angeles to this day was no cosmic accident or mere twist of fate. And much of what we know now of the deliberate action of white supremacists was documented only by a crusading black press.

The historic segregation that defines Los Angeles to this day was no cosmic accident or mere twist of fate. And much of what we know now of the deliberate action of white supremacists was documented only by a crusading black press.

In a new book, City of Segregation, urban geographer Andrea Gibbons explores how a century of structured “regulation, discrimination, structural inequality, and violence” resulted in the fragmented city of today. In the first half of the 20th century, she writes, black-owned newspapers alone reported on the struggle between people of color, who fought to live in their chosen homes, and the white communities that tried to keep them out.

“These were issues that only really affected African-American communities,” Gibbons told Quartz, “and they were completely ignored by the mainstream white-owned newspapers.”

Long before outlets such as the Los Angeles Times even acknowledged problems of discrimination or housing segregation, the black papers covered the issues assiduously, she says. “They played this incredible role, first just in letting people know what was happening, giving people a voice to share what their experience was, and sharing ways to stop it—ways to combat it.”

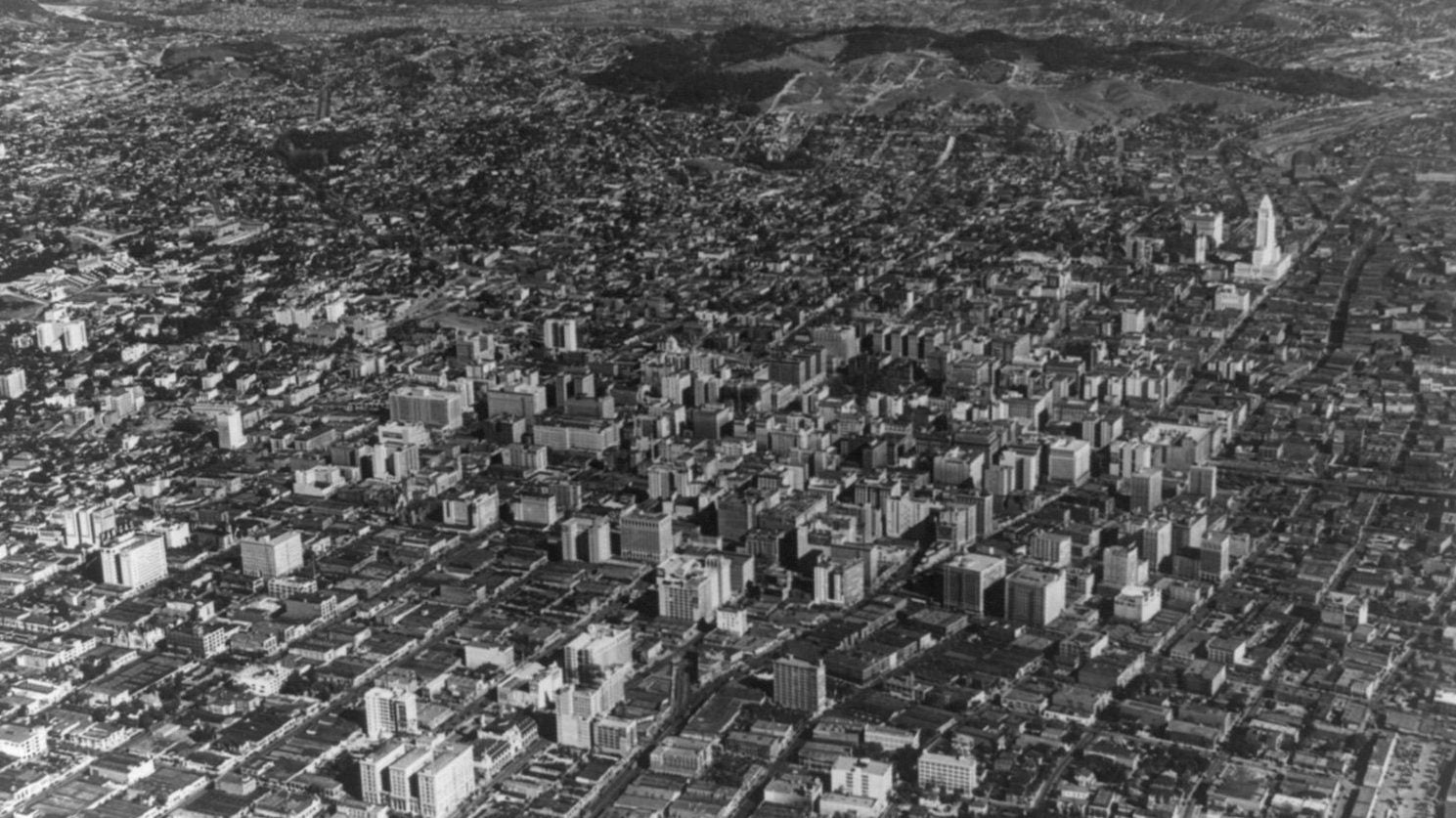

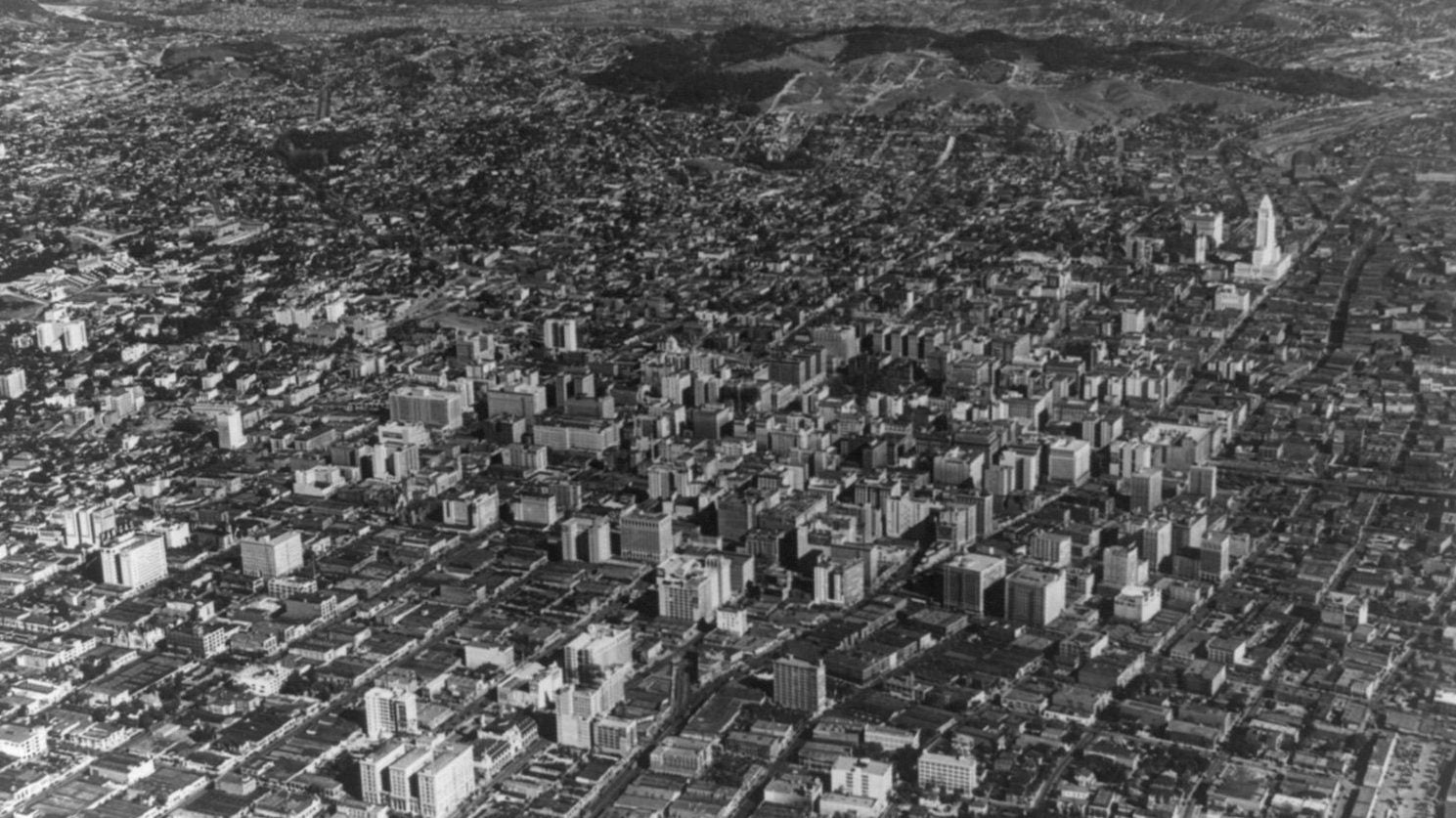

Rather than being a question of individual choice, as economists such as Milton Friedman once suggested, Los Angeles’ present-day segregation—it’s now the 10th most segregated metropolitan area in the US—is the outcome of decades of active effort to keep power in the hands of those who have it. Gibbons’ book chronicles how people of color have been historically confined to areas with poor public services and stagnant property values.

“That’s what I hoped the book would do—to show how powerful these historical currents are, and how deeply embedded racism is into how property is valued,” says Gibbons.

Exposing a long-running system

In the decades leading up to the landmark 1948 US Supreme Court case Shelley v. Kraemer, which prohibited racially restrictive housing covenants, black-owned newspapers such as the Sentinel and the California Eagle recorded the many attempts of white groups to terrorize and segregate people of color and block them from getting mortgages and buying homes. They made housing issues front-page news, placing stories about African-American home purchases outside of the designated “black districts” above the paper’s fold.

The Eagle was owned and run by newswoman and activist Charlotta Bass from 1912 to 1951. Bass arrived in the city from Rhode Island around age 30, and seems to have acquired the paper almost organically from its founder. She remained its sole owner and lead editor. Her husband, Joe Bass, worked as one of her editors. “She faced and overcame all of the challenges offered due to both her race and gender,” writes Gibbons, “and she played a central role in the evolving campaigns to end racial covenants.”

These efforts often went far beyond simple reporting: Mary Johnson, an African-American woman, bought a house on an all-white street in 1914. She returned home to find her possessions strewn across the lawn, and a threatening sign on her nailed-up door. She called the Eagle. Bass “responded in grand style…mobilizing 100 women to go to the house.” They camped out on the lawn and stood guard over her possessions until the sheriff came. “With his help,” Gibbons writes, “the house was opened, the belongings moved inside, and Mrs. Johnson remained in her home.”

At a time when around 10% of the California’s public officials and policemen were Ku Klux Klan members, including Los Angeles’ chief of police and sheriff, Bass’s activism was no mean feat.

The Eagle also covered early legal victories for African-Americans—often cases that represented one step forward and another back. The paper celebrated after the 1919 Title Guarantee and Trust Co v. Garrott case established that restrictive covenants could not restrict the right to “sell or transfer” property—but the result was the simple rewriting of racial restrictions to focus on occupancy rather than ownership.

The Eagle also investigated radical upsurges in white-supremacist activity, while its journalists used their platform to publish the names of racist group leaders and report them to the city council. “They definitely thought of themselves as a voice of the community, and as a force within the community to try and improve things,” says Gibbons.

The war after the war

After World War II, when the city’s African-American population had risen from 75,000 to 134,000 between 1940 and 1944, the newly arrived sought housing reform, including the removal of race restrictions from property. But very little changed.

White-owned papers published headlines like “Keep Maywood White,” while the South Los Angeles Homeowners’ Association issued written advice on how to “Protect Your Home Against the Encroachment of Non-Caucasian People.” It was especially galling for people of color, Gibbons says, “to be drafted into a war that was all about fighting the Nazis and fighting another version of white supremacy that somehow Americans pretended didn’t exist [in the United States].”

Along with local and national civil-rights groups, the Eagle began to use wartime terminology to describe the black struggle for fair housing: “Big guns of Eastside mass pressure will be directed against Housing restrictions which bottle up Negro workers into an area which is the center of slum housing and bum sanitation,” reported the paper. “Such a move is declared to be vital war necessity.”

The Eagle gradually expanded its coverage to include the plight of Native Americans, Asians, Mexicans and Jews, using the same anti-fascist language: ”Negroes must make it hot for all those fascist minded forces which would bottle up American citizens into an over-contested slum area just to placate a Hitlerite theory of race superiority.” In time, Bass used the Eagle’s headquarters for meetings connecting black activists, labor unions, and welfare organizations. The result was the Home Protective Association, an organization run by Bass to fight racially restrictive housing.

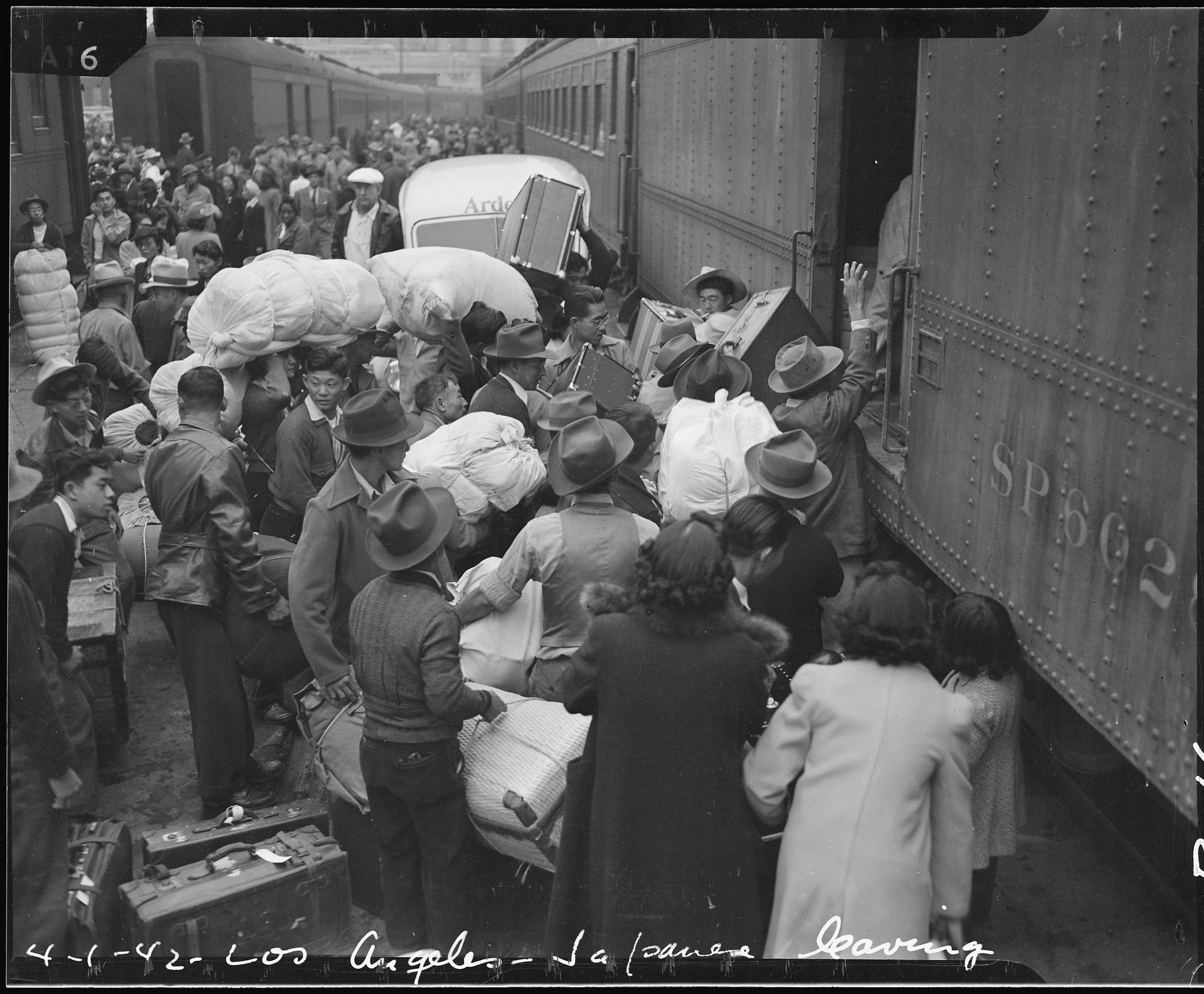

As alliances were built, the HPA published a resolution in the Eagle regarding the return of Japanese Angelenos, who had been interned during the war. Many of their homes had been filled by African-American families during their absence: Now, Gibbons writes, “the HPA firmly supported their absolute right of return,” and called on the government to provide housing both for returnees and for those who would need to be evicted.

A landmark case didn’t change the game

In 1948, the Supreme Court ruled that restrictive covenants were unconstitutional. Shelley v. Kraemer was the product of years of NAACP strategizing and nationwide litigation, and the Eagle, and its African-American audience, celebrated. Other legal victories followed—yet change did not accompany them.

“I think everyone thought once the legal underpinnings of segregation were gone, it would just go away,” says Gibbons. “It was quite a shock when it didn’t—just how deeply it was fought.” Government policy might have shifted, but ideological attitudes had not moved with them.

Black families moved into previously restricted tracts, only to experienced an even deeper level of hostility. When the singer Nat King Cole and his family moved into exclusive Hancock Park, they were met with vocal protest from the local homeowners’ association. Black residents required police escorts to get in their front doors and were the victims of mob violence, arson attacks, and even bombings. In Fontana, a family was burned to death in their home.

The Eagle and the Sentinel chronicled it all—along with mainstream papers, who were beginning to cover the issues that would underpin the wider US struggle for civil rights of the 1950s and ’60s. “The fact that people still kept fighting is quite amazing,” says Gibbons, “But it’s a frightening thought that things became even more segregated through the ’60s and ’70s and ’80s than they had ever had been.”