One economist’s explanation for a baffling mystery of the financial crisis

A lot of things went really badly for the US when the financial crisis hit in 2008. But in at least one respect—for reasons that have baffled analysts—the US got off relatively easy.

A lot of things went really badly for the US when the financial crisis hit in 2008. But in at least one respect—for reasons that have baffled analysts—the US got off relatively easy.

America racked up a mammoth amount of debt in the run-up to 2008, setting the country up for a so-called “balance of payments” crisis, in which the abrupt loss of confidence among foreign creditors destabilizes an economy. (Emerging markets often deal with this kind of crisis, although it can hit advanced economies too—as with the euro area crisis of 2010.)

In this kind of crisis, the steady tide of foreign money that’s been flowing into a country abruptly reverses. Investors panic, yanking their money out of the country en masse. As once-abundant foreign funding disappears, the nation’s currency tanks and interest rates soar, often setting off a chain reaction of defaults. Few countries that borrow excessively for a long time manage to avoid this fate, known as the “sudden stop.”

At certain points in 2007 and 2008, investor panic in the US did set in. Yet the dollar didn’t plunge, and rates didn’t spike. How’d the US get so lucky?

The answer is that it didn’t, according to a blog post by Brad Setser, an economist at the Council on Foreign Relations. He says that the US did experience a sudden stop. And not just one. Between 2007 and 2008, three distinct sudden stops pummeled its financial system. But these stops were offset by a much larger force that ultimately prevented the US from experiencing an even bigger disaster.

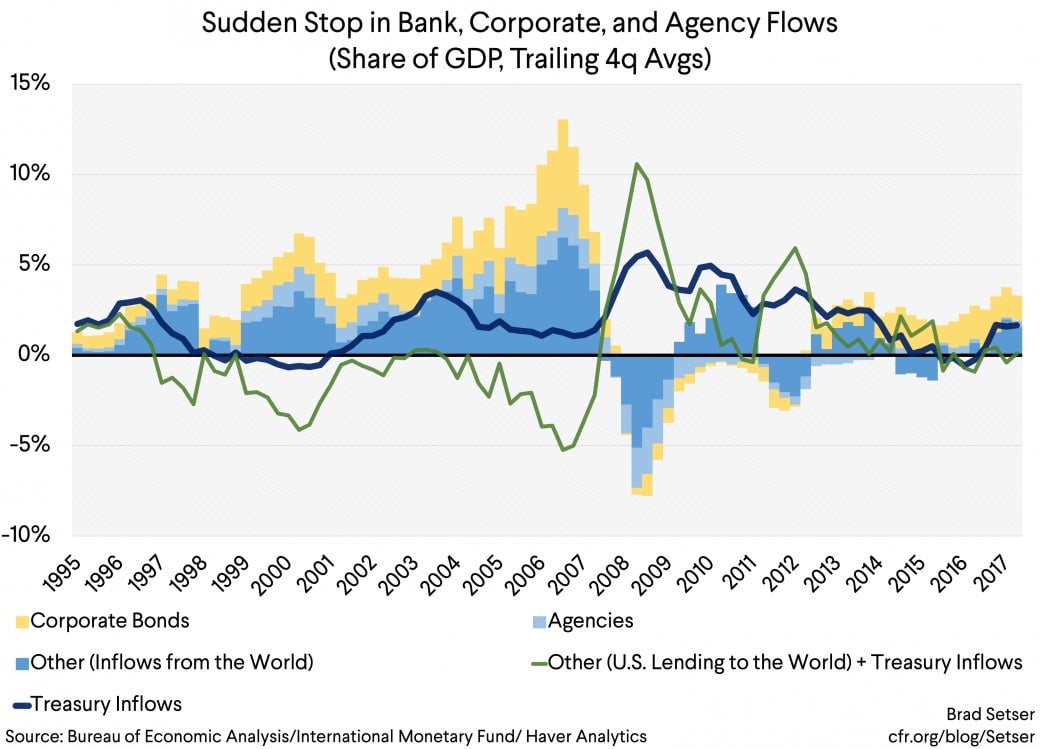

The first sudden stop that Setser identifies hit US corporate bonds—mostly bonds backed by mortgages—in the summer of 2007. Titanic sums of foreign money, equal to around 5% of US GDP at its early 2007 peak, had flowed into those bonds. But as the housing downturn became apparent, foreign investors panicked and sold.

The next stop hit foreign bank inflows—a reversal that was even bigger than the corporate bond collapse, totaling around 10% of GDP between mid-2007 and 2009. “That’s the kind of swing that you see in the most brutal emerging market crises,” writes Setser.

The third sudden stop arrived in mid-2008, when foreign investment in US government-issued mortgage-backed securities (also known as “agency bonds”) swung violently into reverse.

Just as you’d expect, the sudden stops did drag down the dollar, argues Setser. In late 2007 and early 2008, it weakened quite a lot.

The dollar would almost certainly have shed even more value—and US markets would have crashed much harder—if not for the reaction of foreign central banks.

After the crisis hit, central banks in Asia and a slew of oil-exporting countries wanted to prevent their own currencies from rising against the dollar. To counteract that pressure, they bought dollars in what Setser calls “unprecedented quantities,” in the form of the only security big and liquid enough to absorb that demand: US Treasuries. That was a huge force behind the dollar’s post-crisis rally, as well as the relatively quick solidifying of demand for US assets after the crisis hit.

Setser flags another massive, but little-understood, force that braced the US financial system. At the same time that foreign banks were pulling out of US markets, American banks were moving their overseas money—most of which was in offshore dollars—back to the US.

This chart shows the three sudden stops, along with the two offsetting inflows that prevented the US from experiencing an emerging markets-style financial disaster.

Those twin reversals were huge. When US banks directed their overseas money back home, the sum was so large that it canceled out the foreign outflows and then some. By Setser’s calculation, net inflows in 2009 exceeded 2% of US GDP.

Since the gushes of money that American banks poured back into the US came mostly from dollar pools collecting overseas, the greenback’s strength wasn’t affected that much. However, by filling the hole in liquidity created by foreign banks cutting their short-term credit to the US, these moves did stave off the financial catastrophe that the second sudden stop otherwise would have created.

But where did all these foreign central bank dollars come from? Setser’s analysis suggests that they were around before—but they were invested in ways that made them hard to see.

To fund home purchases and consumption, US households needed to borrow. The available creditors were central banks in Asia or oil-rich countries, which had racked up dollars by keeping their own currencies from appreciating (more on how that works here). He continues:

“But central banks, by and large, didn’t want to take the risk of lending to US households. They would buy an Agency—and let the US government (implicitly) take the risk. Or they would put their funds on deposit in a bank (the yield curve was flat, it didn’t mean losing money) or swap dollars for euros (providing a European bank dollar funding, while the central bank could take the euros and buy ‘safe’ European government bonds) and then the bank would buy a package of securitized finance.”

In other words, to keep their exports competitive, foreign central banks hoarded way more dollars than the US government needed to fund its spending. So they had to do something else with the dollars to earn returns. Central banks invested some of them in government-issued mortgage-backed securities. Much of the rest flowed back into the US through a more circuitous route, from central banks to overseas (mainly European) banks, which then used those to buy US mortgage securities. Through either channel, those inflows of central bank greenbacks inflated the US housing bubble even more.

The deluge of capital into the US in the pre-crisis years were what Setser calls the “visible traces” of “complex chains of financial intermediation.” And unfortunately for the global economy, it turned out the intricate lattice of finance linking US homebuyers with foreign central banks was much flimsier than most people realized. “There was a signal there,” writes Setser. “And that signal was, by and large, missed.”