Brazil’s presidential election is so crazy that it’s even drawing comparisons to the US

Faced with two bad choices, people often go for the lesser of two evils. But Brazil’s voters are so unhappy with their options in this year’s presidential election that they may opt out entirely.

Faced with two bad choices, people often go for the lesser of two evils. But Brazil’s voters are so unhappy with their options in this year’s presidential election that they may opt out entirely.

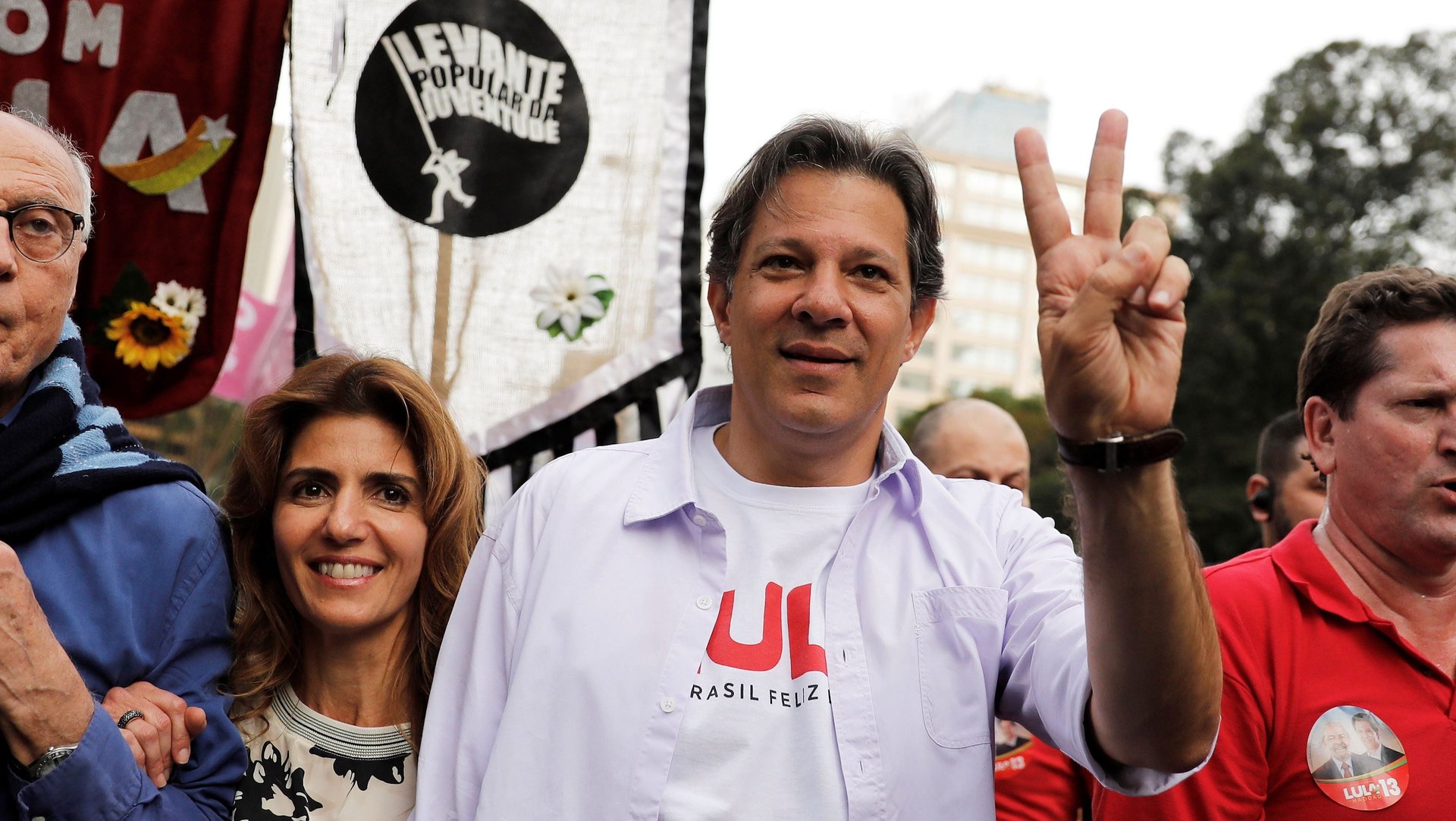

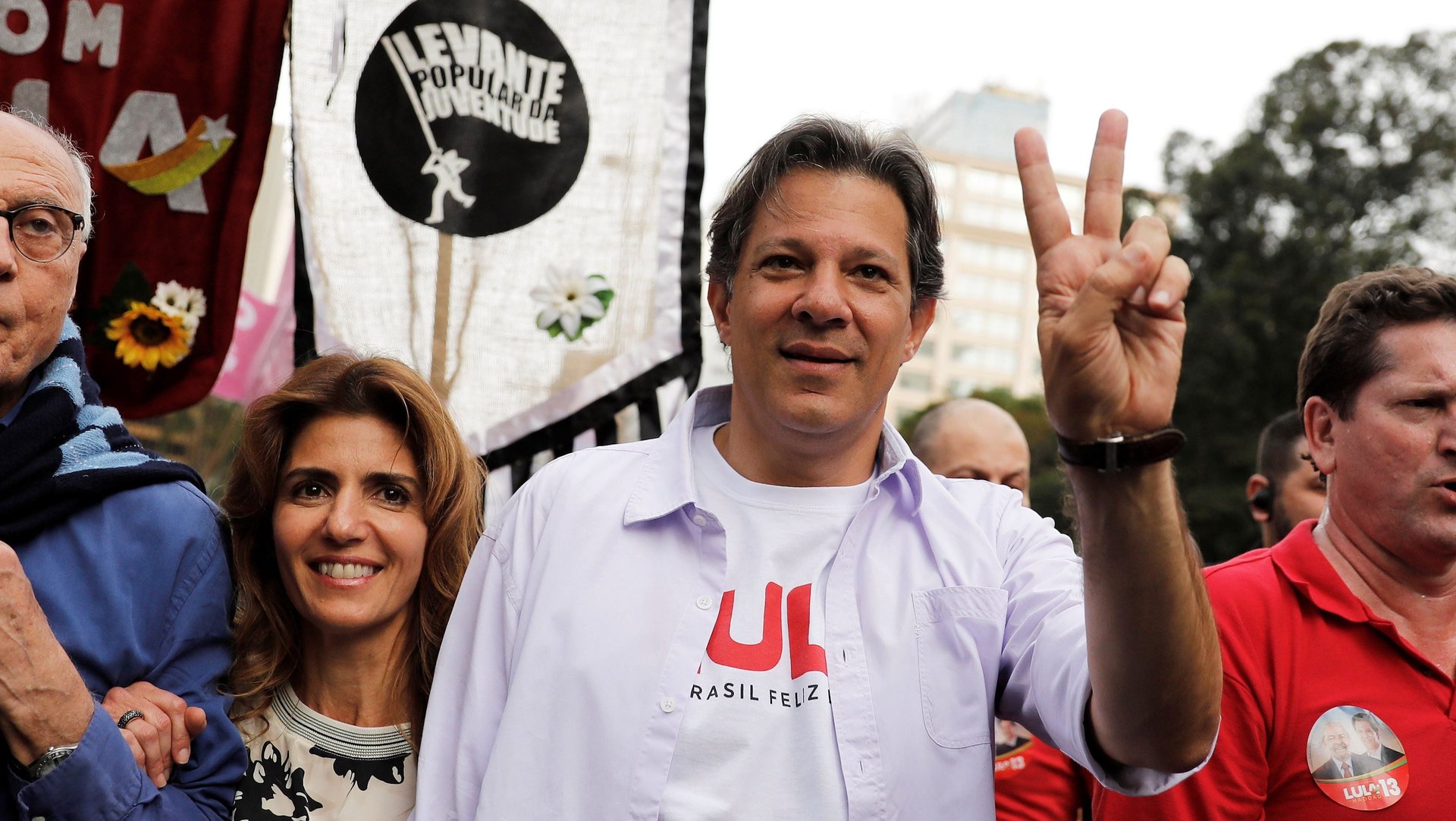

On Oct. 7, more than 147 million Brazilian people will be eligible to vote in the first round of state and federal elections. (In the likely event of a second round, the next vote is set for Oct. 28.) The two presidential frontrunners are Jair Bolsonaro, a far-right, evangelical politician and member of the Social Liberal Party (PSL), and Fernando Haddad, the former mayor of São Paulo and a member of the center-left Workers’ Party (PT).

The choice is less than thrilling for a lot of Brazilian citizens: The Financial Times reports that 11% of voters plan to vote null or blank—the highest figure in 16 years—and another 5% are undecided.

High voter abstention rates are not unusual in Brazil, according to Anthony Pereira, director of King College’s Brazil Institute in London. He says there’s a much bigger problem with this election, one that will sound familiar to many Americans: Whatever its outcome, a large part of the population is going to hate their president from the get-go.

Brazilians are stuck between a rock and a hard place

Bolsonaro, the far-right candidate, has been called the Brazilian Donald Trump. Much like Trump, he markets himself as an “authentic” candidate and a straight talker who refuses to bend to political correctness, while critics accuse him of misogyny, homophobia, racism, and xenophobia. And much like Trump, political analysts see Bolsonaro as a symptom of his country’s deepening democratic crisis. Much of his popular success is owed to the corruption scandals that have plagued the Brazilian government in recent years as well as its recent recession, the worst in the country’s history.

Bolsonaro’ candidacy is evidence of the rise of an ideological right in a country that has long gone without one. ”You’ve got a campaign that’s about God, and patriotism, and guns–all the kind of stuff we’re used to seeing in the Tea Party in the US—that’s coming into Brazilian politics now,” says Pereira.

But while many Brazilians are loathe to vote for Bolsonaro, some say the other top candidate is no better. Fernando Haddad, the former minister of education and mayor of São Paulo, suffers from his association with the Workers Party (PT) and its former leader, Lula Da Silva, who is currently serving a 12-year sentence for corruption and money laundering. “Some people fear that, if Haddad wins, he could pardon Lula, or he could lead some attempts for the PT to get revenge,” says Pereira, “because they have this discourse of the impeachment of 2016 having been a coup … and there may be some fear that they would try to settle scores.”

Pereira warns that if voters are left with a choice between a far-right extremist and a man seen as a symbol of establishment-sanctioned corruption, Brazilian democracy may suffer: ”Even if people vote, and if we have the second round that everyone is predicting now … you’re going to have up to a third, maybe a slightly larger, portion of the electorate that doesn’t accept the election of one of these two candidates.”

Given the tight poll numbers, if even some voters who would normally vote for the center-left Haddad decide to abstain in order to protest their choices, that could swing the election in favor of Bolsonaro. The Economist rather dramatically declared earlier this month, “Bolsonaro, whose middle name is Messias, or ‘Messiah,’ promises salvation; in fact, he is a menace to Brazil and to Latin America.”

That’s why some Brazilians have embraced the idea of a voto util, or “useful vote,” which means voting for whichever candidate that has the best chance of beating Bolsonaro in the second round. That said, voting “useful” is an unsatisfying solution for many people who feel disenfranchised by the democratic process.

Atamai Moraes, a 23 year old medical student from the southern city of Curitiba, tells Quartz that he plans on voting null, or anular, if faced with a choice between Bolsonaro and Haddad in the second round. “Anular is a sign of contempt, a sign of not agreeing with those candidates and their two positions,” he writes over WhatsApp. “There is no actual ideal outcome. Either possibilities are hugely capable [of] irreversibly impair[ing] our democracy.”