The dark future for American workers is still flipping burgers, not freelancing

It’s easy to fear the specter of an economy where millions of people end up with low-paid freelance gigs through TaskRabbit or oDesk, rather than finding full-time work. After all, Silicon Valley’s arrogance never ends.

It’s easy to fear the specter of an economy where millions of people end up with low-paid freelance gigs through TaskRabbit or oDesk, rather than finding full-time work. After all, Silicon Valley’s arrogance never ends.

But even that vision puts a gloss on the real problems with slowly recovering US economy. Today, most unwilling part-timers aren’t freelancing. They’re working in restaurants and retail stores, just like they were before the recession. That’s why the big problem with part-timers isn’t the rise of the freelance economy but the lack of demand in the traditional one.

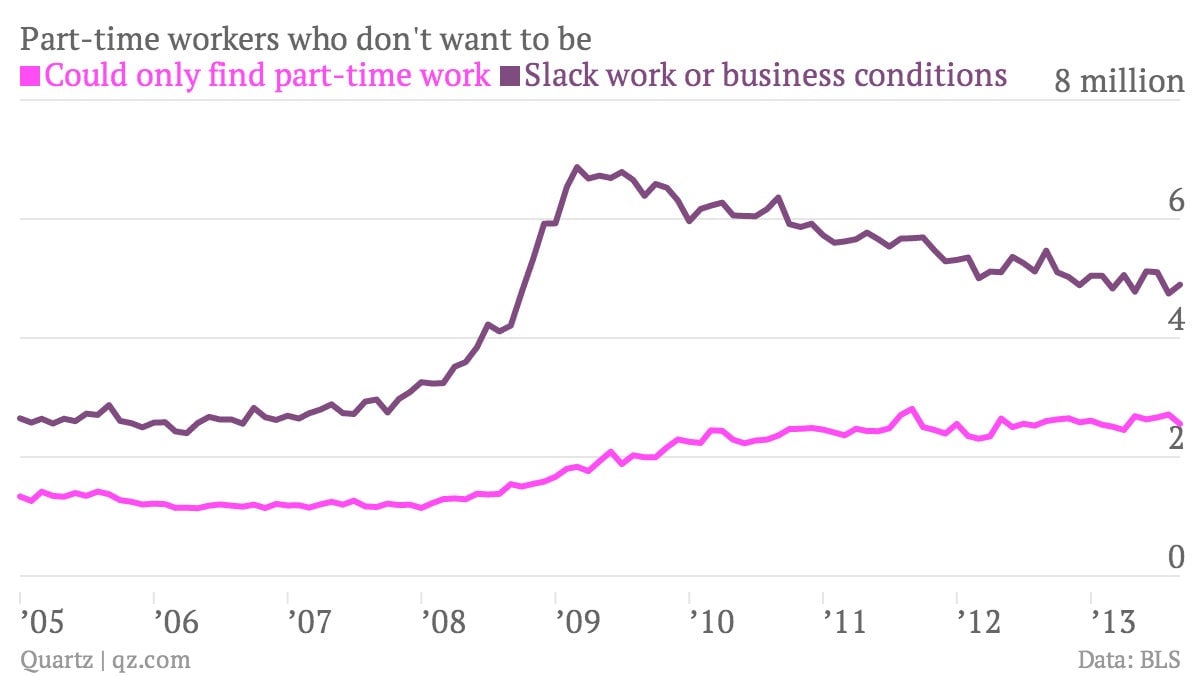

We’re talking about people who are employed part-time but would rather work full-time. (About 18 million Americans work part-time because they want to, about the same today as before the crisis.) Today, 7.5 million people are involuntary part-time workers, a little more than 5% of the workforce. Here’s how the Bureau of Labor Statistics breaks down the two types of part-time workers:

In terms of industries, 1.5 million unwilling part-time workers are at restaurants and hotels; another 1.4 million are at retail stores and distributors; and 1.2 million are in education and health care. Rounding out the top five sectors are 780,000 self-employed workers (where the modern-day valets of TaskRabbit are counted, among freelancers of all kinds) and the 661,000 providers of professional services, everything from lawyers and architects to photographers and veterinarians. Here’s how those five sectors have grown since before the crash:

Those same industries contained the most involuntary part-time workers in 2005, too, except that professional services replaced construction, a sector that has shrunk enormously since the end of the housing bubble. While the number of self-employed, involuntary part-timers has increased since then, it’s been eclipsed by the trend toward part-time employment in the three larger sectors, as you might expect.

Most explanations for the trend are straightforward, too: Companies want to find ways to avoid paying for workers’ benefits (a trend that, incidentally, kicked off well before Obamacare was conceived) and companies don’t have enough business to justify having full-time workers—by far the larger problem, as you can see in the first chart above.

The rosy view is that more and more of those part-timers continue transitioning to full-time jobs as the economy recovers, but that’s been a frustratingly slow process. The dark view isn’t the rise of the part-time “gigwalker“—it’s the rise of the part-time dishwasher.