White supremacists are taking their design seriously—and we should, too

Renowned illustrator Mirko Ilić silenced the crowd of logo-happy graphic designers at the Brand New Conference in New York City last month when he suggested that many of them may not notice symbols of white supremacy hiding in plain sight. In a stunning call-to-arms, the 62-year old designer and educator called on his audience to be the vanguard for raising awareness about such hateful marks.

Renowned illustrator Mirko Ilić silenced the crowd of logo-happy graphic designers at the Brand New Conference in New York City last month when he suggested that many of them may not notice symbols of white supremacy hiding in plain sight. In a stunning call-to-arms, the 62-year old designer and educator called on his audience to be the vanguard for raising awareness about such hateful marks.

“We’re all designers: We make our clients rich, [and] in the process we make ourselves wealthy and secure our future. But we sometimes forget that we’re first all citizens of this country and of the world,” began Ilić, who has been lecturing about Neo Nazi’s iconography for the last six years. “We all know about logos and emblems—we breed them, we create them, we copy them, and combine them. It’s our job to share this with the public because we can see logos and symbols before them,” he said.

Later, Ilić elaborated to Quartz: “Our duty is to tap on the shoulders of fellow citizens and say, ‘do you know what that means?'”

Fascist groups have usurped ancient symbols for their own propaganda, Ilić pointed out, and he believes it’s crucial for designers to be knowledgeable about their shifting significance—even for the purposes of avoiding the embarrassment of inadvertently using them in corporate logos.

Here are several loaded symbols Ilić identified, many of which are included in the American Defamation League’s database of hate symbols.

The X Mark

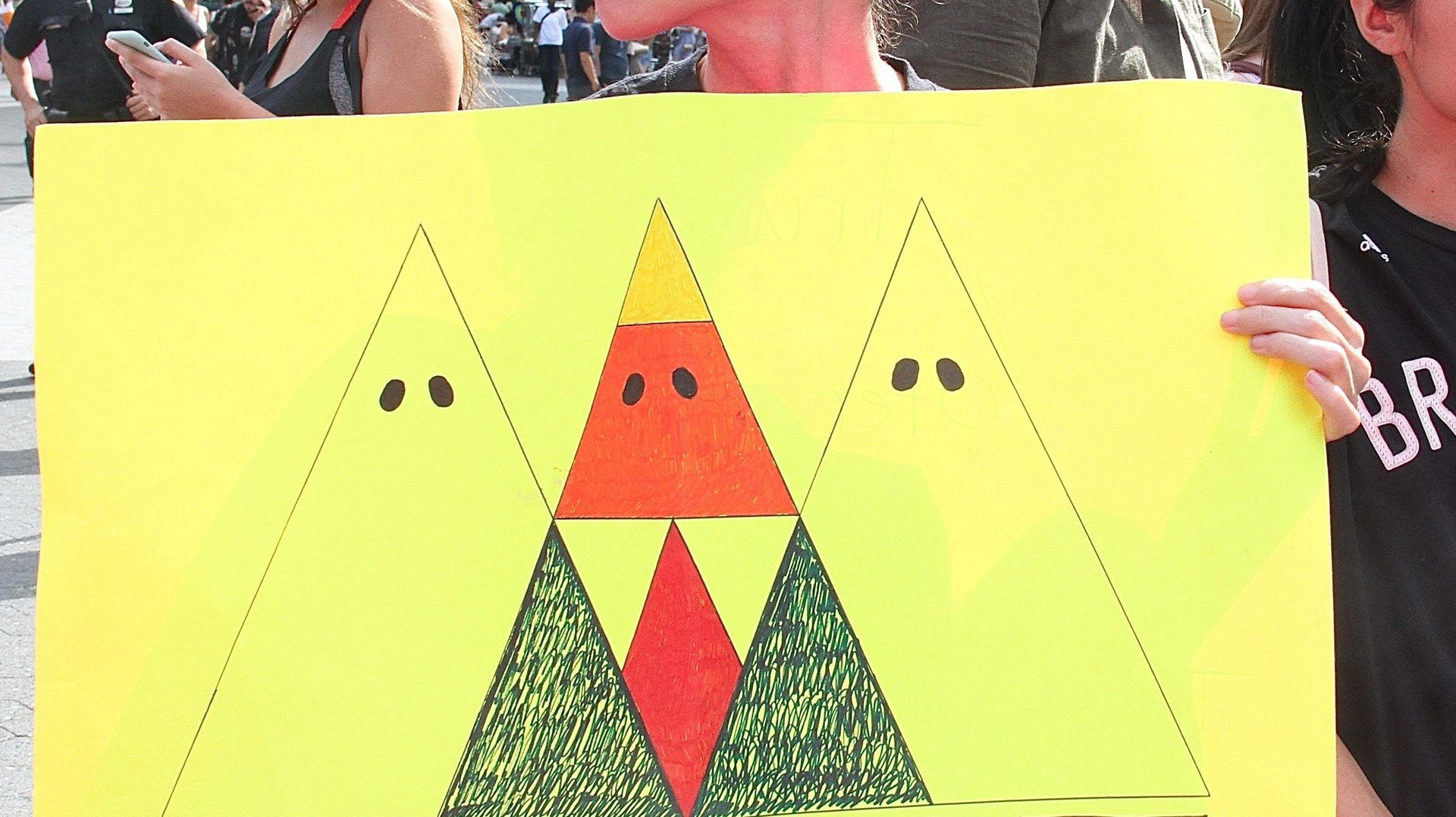

A black X that stretches across a white pennant was first spotted in the 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. The symbol is an abstraction of the US confederate flag.

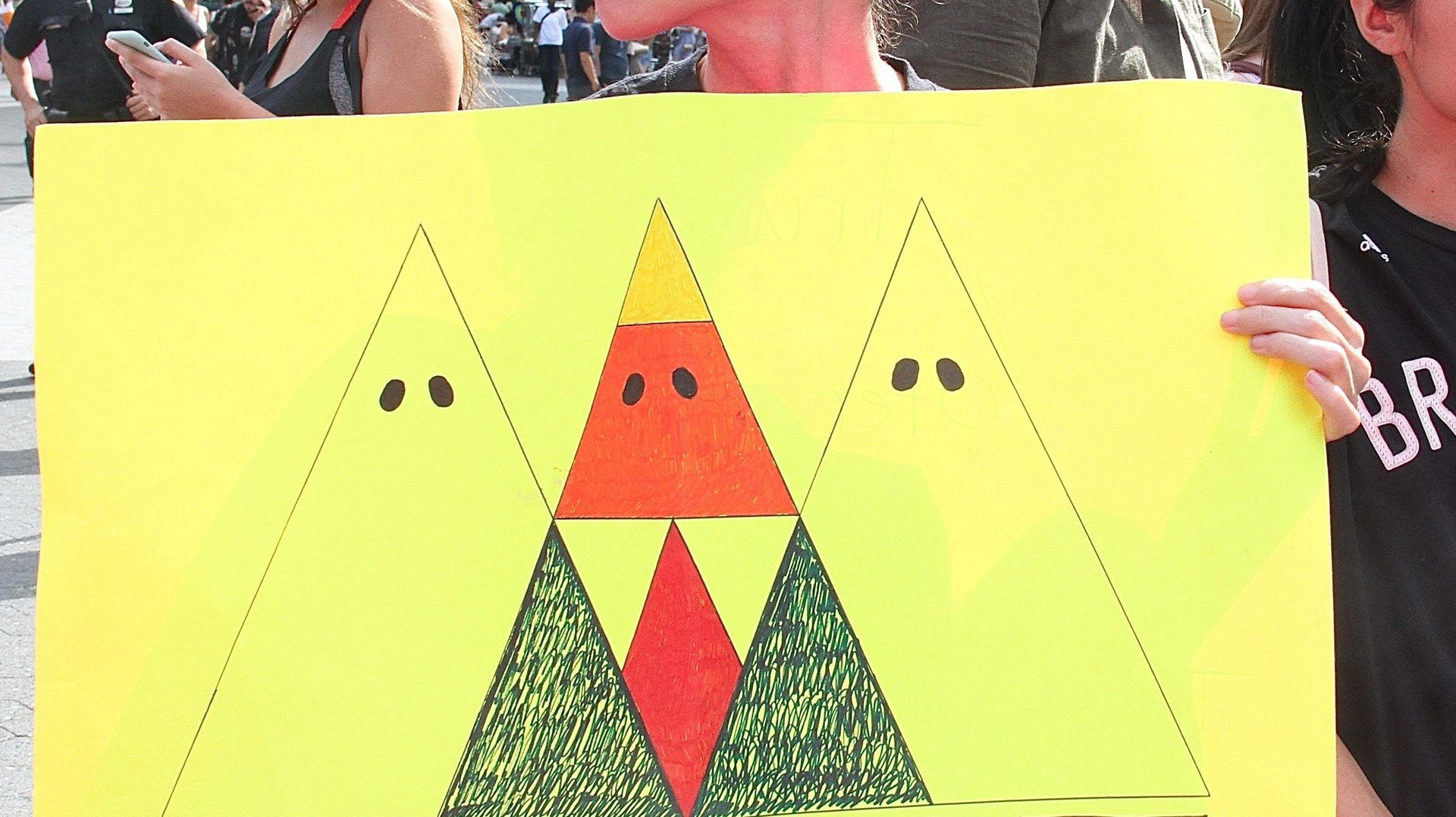

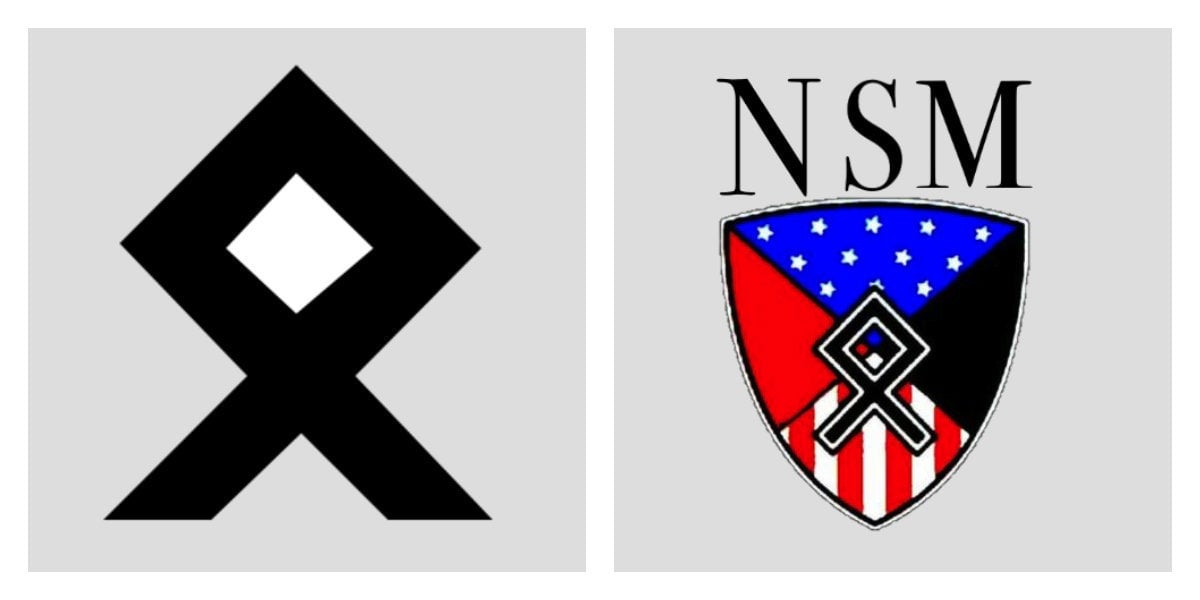

Othal rune

The incendiary flag of the National Socialist Movement features the ancient symbol of Othala, which connotes heritage and tradition. The Detroit, Michigan-based Neo-Nazi political party replaced the swastika with the Nordic symbol on its flag in 2016 in “an attempt to become more integrated and more mainstream,” explained spokesperson Jeff Schoep to the New York Times. German Nazis also wielded the Othal rune (aka Odal rune or Norse Rune) to symbolize Blut und Boden (“Blood and Soil”), an ideology that solely defines ethnicity based on one’s blood descent.

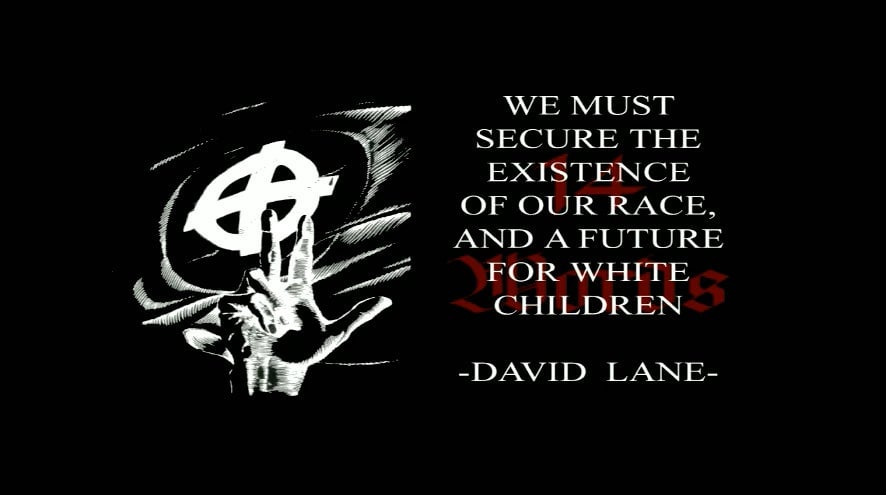

The number 14

According to Ilić, the number 14 represents the 14 most important words of white supremacist ideology:

Formulated by white supremacist felon David Eden Lane, the statement succinctly summarizes the goals of the movement. Lane further expanded on the “Fourteen Words” while serving a 190-year prison term. He wrote the 88 Precepts treatise which contains guidelines on how to preserve power established by white nationalists in North America and Europe. The number 14, at times coupled with 88 (for “Heil Hitler,” repeating the eighth letter of the alphabet), often appears on banners in Neo-Nazi gatherings.

The Celtic cross

“It’s now the symbol of one of the most violent skinhead groups,” explained Ilić, referring to the traditional Ku Klux Klan icon. Sometimes known as “Odin’s cross,” the symbol also appears on the flags of the National Front in England; the logo of the leading anti-semitic forum Stormfront and fan swag for the racist band Skrewdriver. Nazi’s flash the Celtic Cross to convey white pride.

Of course, the Christian symbol appears extensively in other contexts—churches, crosses, the Irish Football Association logo—so one should be careful about automatically classifying it as a hate symbol.

Displaying the Celtic cross, along with the rune and other Nazi symbols, is prohibited in Germany if they’re used with other racist symbols. German game companies, however, succeeded in convincing the government to bend the rules and allow Nazi symbols in World War II-themed video games.

“Neo-Nazis and white supremacist are starting to get good design,” Ilić said. “They have obstacles and they have to figure out. They take themselves seriously, we don’t take them [the symbols] seriously. Because of that they’re doing a better job,” he says.

Born in the former Yugoslavia, Illic valued political participation at an early age. Apart from lecturing about Neo-Nazi iconography, he also organizes the Tolerance Poster Show, a traveling exhibition of 98 posters by designers from 40 countries. “I’m trying to be proactive,” he says. “I’m trying to point to danger and on one hand, and show a visual alternative with the poster show.”

Ilić lamented the American graphic design industry’s apathy toward learning about coded symbols of hate. He said even the accidental appropriation of these loaded marks makes them seem legitimate or innocuous. “Not allowing them to be the ‘new normal’ is very important,” he said. “Maybe one of these days, a major studio will [accidentally] use it, and we’ll finally pay attention.”