Sexism at Wikipedia feeds off the sexism in the media

In May, a volunteer editor at Wikipedia rejected a submitted biographical article about Donna Strickland, on the grounds that the laser physicist did not meet the site’s “notability guidelines.” This week (Oct. 2), Strickland won the Nobel Prize for her work on ultrashort lasers.

In May, a volunteer editor at Wikipedia rejected a submitted biographical article about Donna Strickland, on the grounds that the laser physicist did not meet the site’s “notability guidelines.” This week (Oct. 2), Strickland won the Nobel Prize for her work on ultrashort lasers.

Her omission from the internet’s encyclopedia prompted accusations of gender bias at Wikipedia, leading founder Jimmy Wales to conclude that the site “needs to change.” But it’s also a pointed lesson in the hazards of gender bias in media, and of the broader consequences of underrepresentation.

In rejecting the Strickland article, the Wikipedia editor said the author’s references did “not show significant coverage (not just passing mentions) about the subject in published, reliable, secondary sources.” In other words, Wikipedia relies in part on the judgment of other gatekeepers to determine whether a person is noteworthy. That’s a problem, because on the whole news outlets and journalists—even well-intentioned ones—have a dismal track record at equitably representing women in their coverage.

Multiple analyses have found that, on average, men are quoted more often in news coverage than women by a factor of roughly three to one. The problem is particularly pronounced in coverage of STEM industries, where women are already in the minority.

Adrienne LaFrance, editor at the Atlantic.com, analyzed her own science stories published in 2013 and 2015 and was dismayed to find that women were quoted in less than 25% of them. Her colleague Ed Yong did the same, and was likewise chagrined to find that only 24% of the people quoted in his stories were women.

LaFrance and Yong are conscientious reporters; neither wants to perpetuate bias. By scrutinizing their own work, they show that when we ascribe authority only to people already identified as “experts” by those before us—as Wikipedia and many of us journalists do when quickly evaluating whose expertise is worthwhile—we absorb those earlier judges’ biases as well.

“We don’t contact the usual suspects because we’ve made some objective assessment of their worth, but because they were the easiest people to contact,” Yong wrote. “They topped a Google search. Other journalists had contacted them. They had reputations, but they accrued those reputations in a world where women are systematically disadvantaged compared to men.”

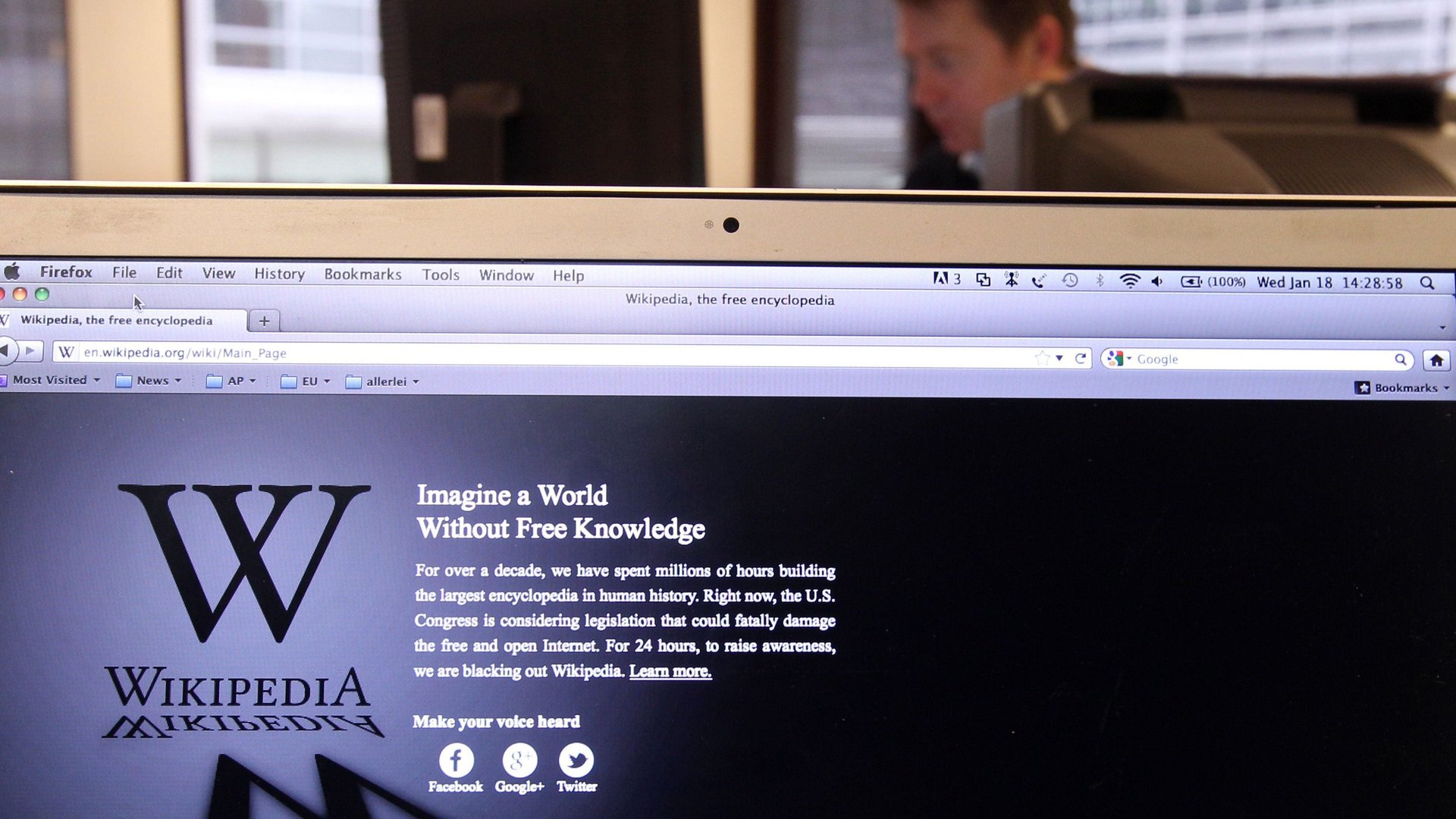

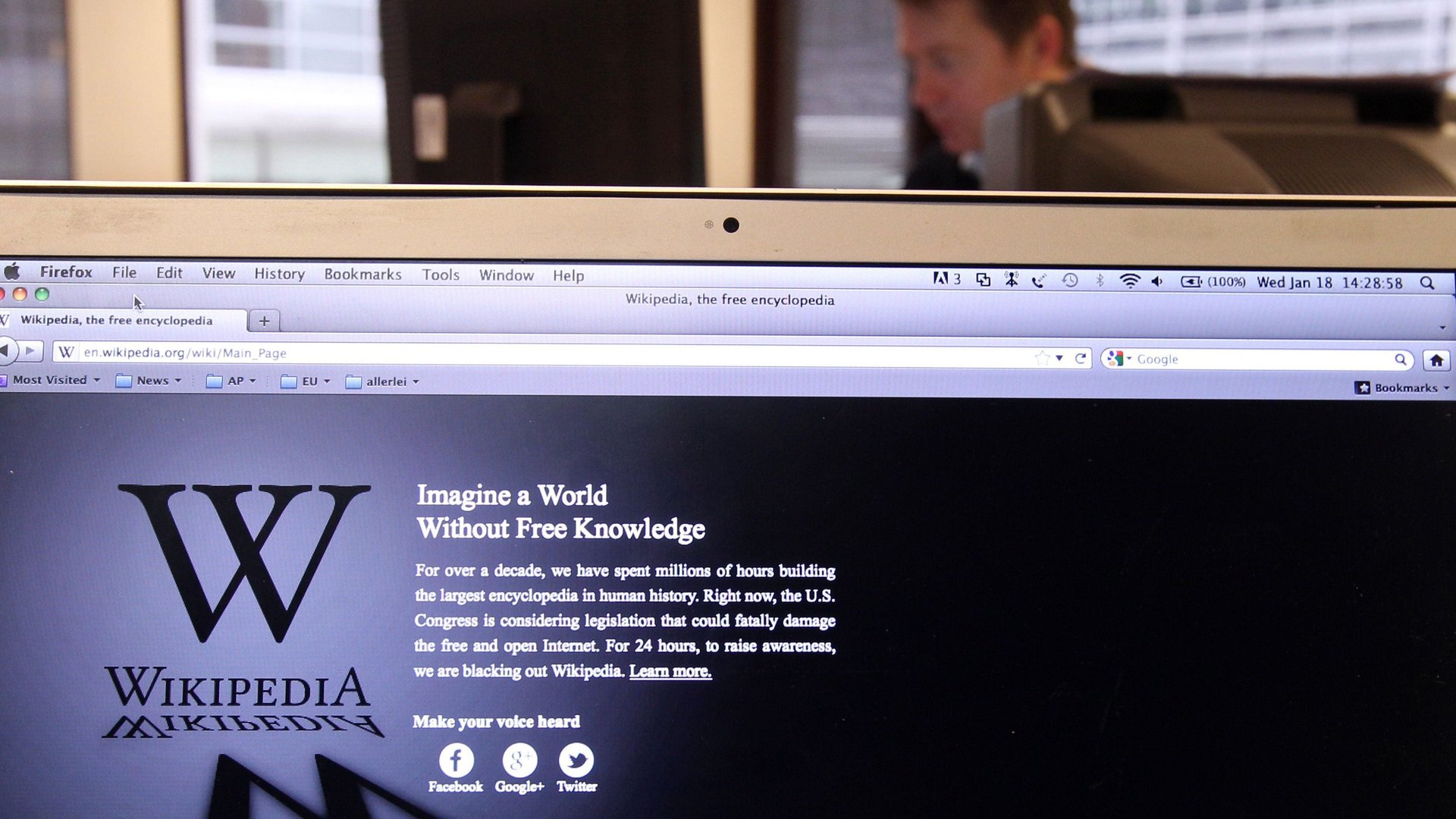

And what usually tops a Google search? Wikipedia. “A Wikipedia biography can give a scientist credibility,” Jess Wade and Maryam Zaringhalam wrote in Nature in August. The two are members of 500 Women Scientists, a group working to change perceptions of women in STEM. Adding biographies of women scientists to Wikipedia is one of their efforts.

“As with any democracy, results are determined by those who choose to participate,” they noted. “Who edits Wikipedia—and the biases they carry with them—matters.”

Only 17% of English-language biographical articles on the site are about women, which is about the same proportion of Wikipedia editors who are female. The site’s own guidelines make clear that media coverage isn’t the only criteria for inclusion, especially for scientists; that standard doesn’t always seem to be fairly applied. At the time Strickland’s bio was rejected, the only cited sources on the live biography of her male collaborator Gérard Mourou were his faculty pages and links to the awards he’d received—evidence deemed insufficient in his female colleague’s case.

Clearly, scientists like Strickland are still doing groundbreaking work, even without Wikipedia entries or copious media coverage. But her exclusion from the world’s fifth-most popular website is a good reminder that the volume of a subject’s media coverage often says more about gatekeepers’ priorities than the achievements of the subjects themselves.