How Turkey made its railway tunnel under the Bosphorus earthquake-proof

This week, the world’s first transcontinental tunnel was opened in Turkey.

This week, the world’s first transcontinental tunnel was opened in Turkey.

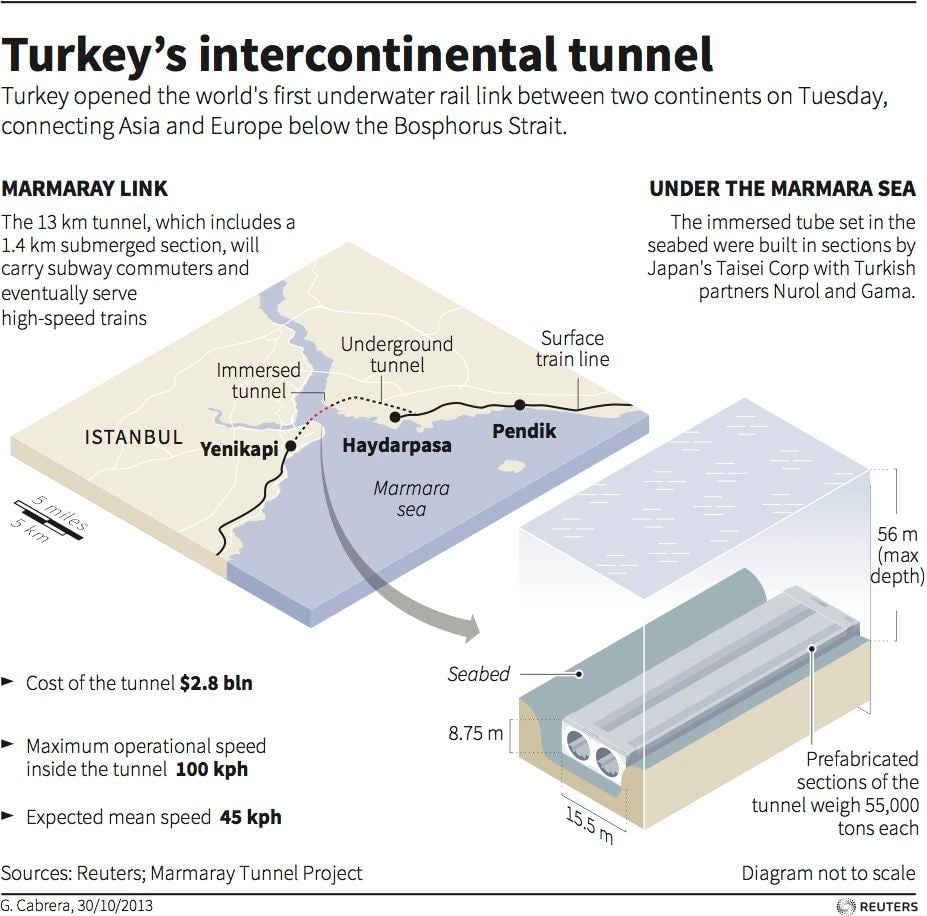

Istanbul’s Marmaray tunnel connects Europe and Asia, delving 1.4 kilometers (0.87 miles) across the Bosphorus Strait at a depth of 60 meters (185 feet), breaking records for an immersed tube tunnel. The name is a portmanteau of “Marmara” (the Turkish body of water just outside the strait) and “ray,” the Turkish word for “rail.” As construction was a mere 20 kilometers from the active North Anatolian earthquake fault, the tunnel segments had to be built to withstand earthquake magnitudes up to 9.0.

The tunnel, a pet project of controversial prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan, was nine years in the making, and cost an estimated €3 billion ($4.08 billion). It’s one of a number of projects that Erdogan hopes will help double Turkey’s GDP in the next decade (paywall).

The project was delayed for over two years by engineering problems and repeated archaeological discoveries. But archaeologists say that the artifacts unearthed as workers pressed along the muddy strait are invaluable to our understanding of Turkey’s ancient Byzantine history.

Each tunnel segment was constructed as an immense tube, floated into the strait in pieces, then sunk and dug into position, under 15 feet of silt. In order to protect the tunnel from quakes, segments were constructed to capitalize on the softness of the muddy strait floor, which was stabilized with injections of special caulking. The whole assembly is designed to bend, not break, in the event of an earthquake—even if tremors are severe enough to liquefy the underlying earth. In addition, each section has its own flood wall gates, designed to slam down in the event of a breach. The formula for the tunnel’s prefabricated quick-strength concrete features a nano-engineered polymer from BASF.

However, train service—now linking Istanbul’s districts of Yenikapı and Üsküdar on their respective European and Asian coasts—didn’t go without a hitch, and there are reports (link in German) of malfunctioning train doors, missed train stations, and passengers resorting to walking. Turkish State Railway officials attribute the problems to passengers activating the emergency stop, a city power outage, and “unexpected passenger congestion.”