Brazil got it wrong today. It needs to keep its productivity high, not its currency low

Brazil watchers held their breath today as the Central Bank of Brazil cut the benchmark interest rate (the Selic rate) to 7.25% from the current level of 7.5%, which already was the lowest in decades. The decision was not a unanimous one, signaling there may be little more the prestigious Brazilian economic team can do.

Brazil watchers held their breath today as the Central Bank of Brazil cut the benchmark interest rate (the Selic rate) to 7.25% from the current level of 7.5%, which already was the lowest in decades. The decision was not a unanimous one, signaling there may be little more the prestigious Brazilian economic team can do.

The game is one of high stakes. The rate of growth of the Brazilian economy declined from an almost all-time record of 7.5% in 2010 to 2.7% in 2011. Year-on-year growth in the second quarter of 2012 was a paltry 0.49%. Moreover, foreign investment has fallen big time and the prices of shares have declined by 5.2% this year. Inflation is increasing to 5.6%. The bank’s market lending interest rates (that is, those not subsidized by the government) have declined from levels above 80% a decade ago to 37% today—a large decline, but not enough to awaken enthusiasm for borrowing in Brazil.

Finance minister Guido Mantega has a strategy to meet these challenges. His mind has been focused for long on what he calls the “currency wars,” the race to the bottom that is now taking place in the currency markets. His view is that the aim of each participant in this war is to devalue the currency faster than the rest of the world, apparently on the belief that the farther you devalue, the further you grow because you would be more “competitive”—meaning cheap.

Brazil’s main adversary in this war, Mantega maintains, is Mr. Ben Bernanke, who is flooding the world with dollars, depreciating them against all other currencies. The entry of these dollars into Brazil would make the currency, the real, appreciate, scoring a point for Bernanke and pushing down the rate of growth of the Brazilian economy. But speaking today from Tokyo, Mr. Mantega reassured the world that the real is protected against Mr. Bernanke’s plots by several “lines of defense”, which include a tax on financial transactions, declining interest rates, and huge programs of fiscal expenditures and monetary creation. This, Mr. Mantega thinks, will slow down the entry of dollars into Brazil. With lots of reais being created, the domestic currency will depreciate, spurring growth.

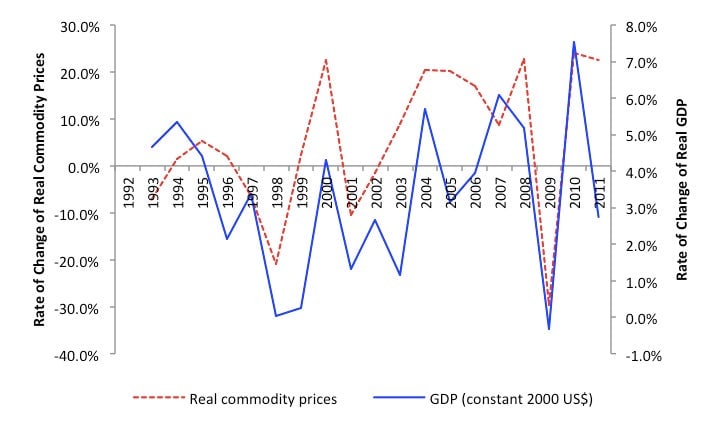

The strategy is impressive. Yet, there are reasons to be skeptical about its effectiveness. The chart below (figure 1) shows how the rate of growth of the Brazilian economy has shadowed the rates of change of commodity prices in the last twenty years. The economy has tended to expand when commodity prices are high, and to go slow when those prices are low. That is, in Brazil growth depends pretty much on luck. The fantastic rates of growth of 2007, 2008 and 2010, and the stagnation of 2009 are fully explained by the movements of commodity prices, not by the value of the real or subtle movements in the Selic rate.

Now, you could argue that the correlation between commodity prices and growth is not perfect. Other factors influence growth. Surely currency depreciation must have been a positive factor in the past in terms of inducing production, attracting good capital inflows, and restraining inflation, you may think. If not, would Mantega be fighting so strenuously to devalue the real?

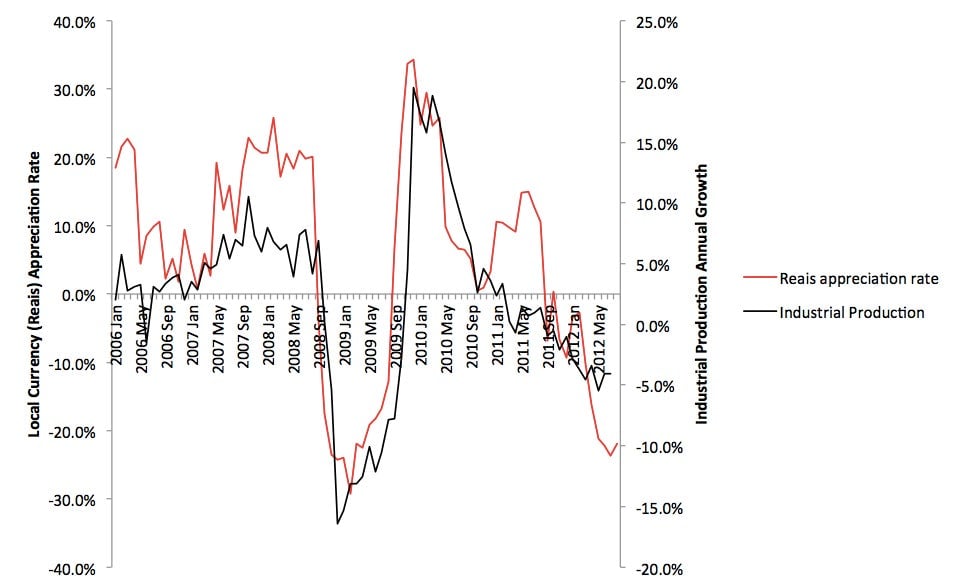

That is why figure 2 is so shocking. It shows that industrial production has in fact tended to increase when the currency appreciates, and to decrease when the currency depreciates. The latter is what has been happening in the last year. The more successful Mantega has been in devaluing the currency, the faster has industrial production declined. Could it be that Mantega has things back to front?

Why does this happen? In fact, what makes industrial production increase when the currency appreciates is not the fact that the currency has appreciated, but that both variables turn out to depend on a third one, the one that spurs growth—the inflows of dollars that the finance minister hates so much. During the last few years, the flow of dollars has increased dramatically for two reasons: the commodity-prices boom that started in 2004, which generated dollars, and the high interest rates prevailing in Brazil, which attracted the dollars to the country. These capital inflows made the real appreciate, which made the yield of Brazilian interest rates go up in dollar terms, which in turn attracted even more capital, in a virtuous cycle. Thus the Brazilian economy boomed, generating the idea that it would become the engine of the world. Of course, the fuel of the engine was dollars, and the exceptional prosperity would last only as long as the dollars kept on coming.

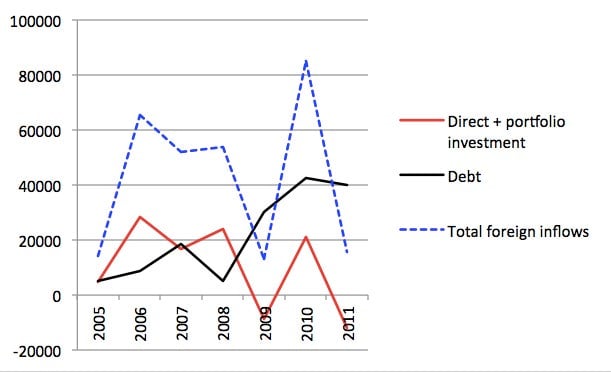

Then, in 2011 the prices of commodities began to fall. The dollars began to dry up. This and Mantega’s policies slowed down the inflow of capital. The currency began to depreciate, lowering the yields of Brazilian interest rates in dollar terms, making Brazil less attractive—the reverse of the virtuous cycle during the boom. As shown in Figure 3, direct and portfolio foreign investment fell from their 2006-2008 highs, and, though they recovered in 2010, they became negative (capital left Brazil) in 2011. It was only because debt increased substantially that total capital inflows remained positive in that year. But, as the currency depreciated, the prices of shares declined as well (see Figure 4). Additionally, currency depreciation exerted upward pressure on prices, via the costs of imported and exported goods and services.

Thus, Mantega has succeeded in depreciating the Brazilian currency, mightily helped by the decline in commodity prices and capital inflows. But this looks like a Pyrrhic victory, because, along with the depreciation, inflation is increasing, share prices are falling, and capital inflows and production are declining. Not what he said he wanted to achieve.

Maybe Mantega has truly lost his bearings. The true battle is not in depreciating the currency, or in appreciating it, or in keeping it stable. It lies in improving productivity, which is so low in Brazil that the country enters into periods of macroeconomic instability whenever it receives the substantial capital inflows it needs to upgrade the country’s infrastructure to developed-country standards. If the government took the measures needed to improve the country’s productivity, it would not have to worry about Bernanke inundating the place with dollars. Brazil would take full advantage of them.