The complicated legacy of modern Japan as it celebrates its 150th birthday

The modern state of Japan came into being on Oct. 23, 1868, when the Edo era ended and the Meiji emperor ascended to the throne.

The modern state of Japan came into being on Oct. 23, 1868, when the Edo era ended and the Meiji emperor ascended to the throne.

The Meiji Restoration, as the event came to be known, marked the start of Japan’s ambitious rise to a global power that, for the first time in history, would see an Asian country stand shoulder-to-shoulder with European powers—which, while a source of pride for many Japanese (and even for some in neighboring countries), also culminated in Japan’s destructive quest for empire in the following century.

While Japan’s rapid rise to become one of the world’s most powerful countries is nothing short of remarkable, its history of conquest has made the legacy of Meiji an uncomfortable one in the post-war era. Today, nationalism is once again on the rise under the leadership of Shinzo Abe—who has tried to channel the spirit and goals of the Meiji era in his quest for a Japanese rejuvenation—making a look back on the Meiji Restoration all the more pertinent.

What did Japan look like before 1868?

The period before the Meiji era was known as the Edo era (1603-1868), when Japan was ruled as a collection of fiefdoms under the Tokugawa shogunate, a military dictatorship that was based in Edo (present day Tokyo). Society was highly stratified, with the feudal warlords, or daimyo, at the top, and the samurai warrior class just below them. Merchants, artisans, and farmers were at the bottom. The emperor, residing in Kyoto, in practice had very little political power.

Japan was militarily weak, technologically backward, and almost entirely closed off from the outside world in a policy known as sakoku, or “locked-up country.” Driven in part by a fear of the spread of Christianity after Europeans first landed in the 16th century, any contact with foreign countries was almost entirely limited to a port in Nagasaki.

Why and how did Japan decide to modernize?

The final years of the Tokugawa shogunate were marked by growing internal discord and political challenges against the ruling classes, but it was the arrival of commodore William Perry’s fleet of four ships—known as kurofune, or the black ships—from the US in 1853 in present-day Yokosuka that destabilized Japan more than anything else, forcing it out of its sakoku status. To this day, new foreign ideas that enter Japan to disrupt the status quo are still referred to as “black ships,” such as Spotify.

The US and other Western powers would eventually impose unequal treaties on Japan to force it to open up trade to other countries. Anger was rising against the shogunate for its inability to prevent foreign powers’ unequal treaties. An organized rebellion came from a group of nationalistic, lower-ranking samurai in the western domains of Satsuma and Choshu in present day Kyushu, who understood that Japan needed to modernize in order to repel the Western powers, and who believed that the sidelining of the emperor in politics was something that needed to be addressed—a belief that was encapsulated in their slogan “Revere the Emperor, Expel the Barbarians.”

The ensuing years were chaotic and violent, with Choshu forces attempting to seize control of the imperial Kyoto court. Foreigners and Japanese who collaborated with foreigners were also targeted, including an Englishman who was killed in Kanagawa in 1862. In the meantime, both the shogunate and the western domains had been busy modernizing their militaries along Western lines. The two sides ended up fighting in what is known as the Boshin War, with the 15-year-old Meiji emperor declaring his restoration to full power in January 1868. The Meiji era (which means “enlightened rule”) was officially established on Oct. 23.

Fighting, however, continued into 1869 and beyond, and the imperialists also abandoned their goal of expelling foreigners to focus on modernizing Japan.

What did it mean for Japan to become a “modern” country?

Japan’s path to modernization was laid out in the Charter Oath, presented by the emperor in April 1868, which essentially pledged the establishment of assemblies and public discussions for governmental matters, greater equality among classes, and the abolition of “evil customs” from the past.

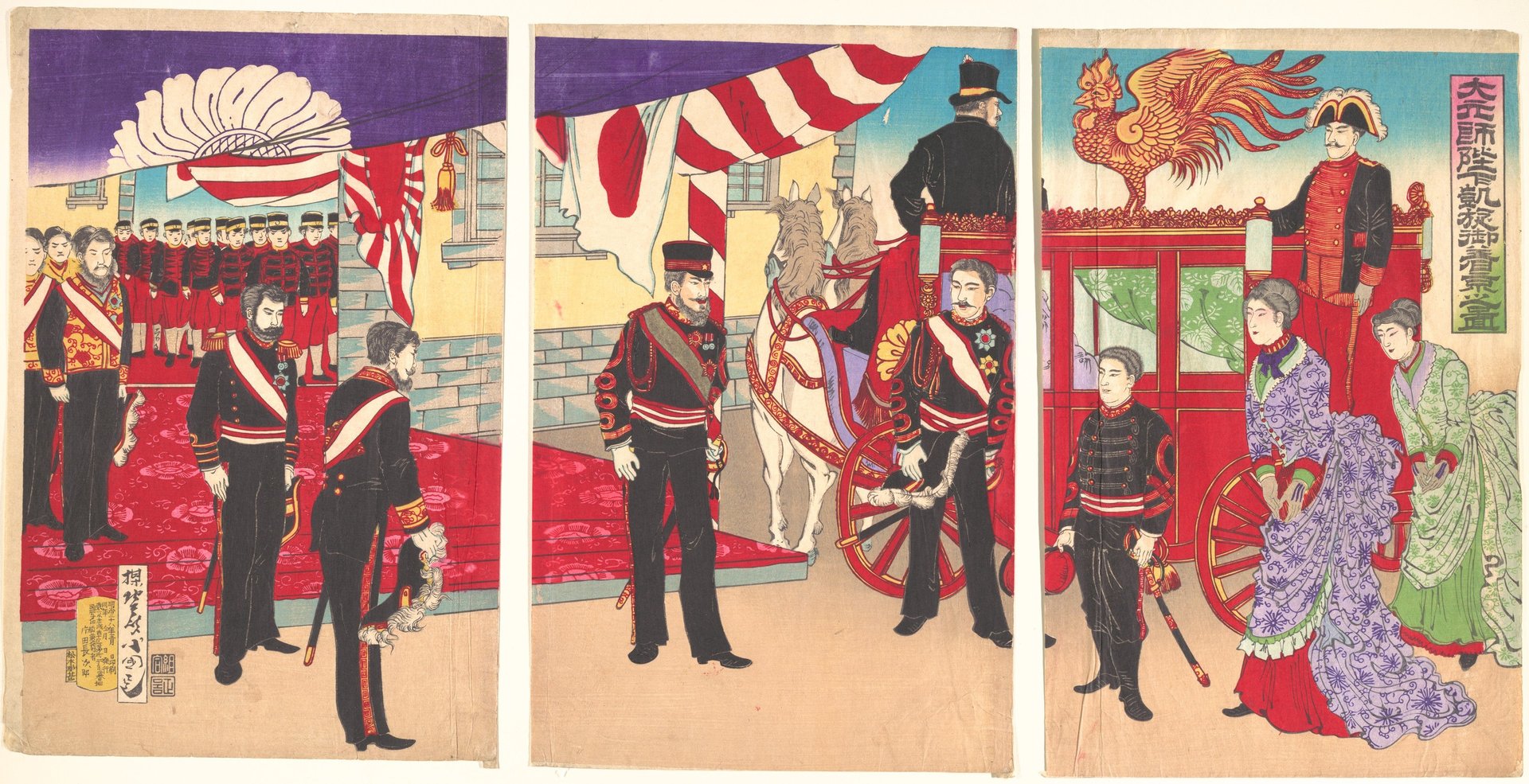

Other slogans that were in use at the time crystallized what Meiji leaders believed made a modern nation: bunmei kaika (civilization and enlightenment), fukoku kyohei (rich country, strong army), and shokusan kogyo (encourage industry). Being civilized, for example, meant adopting Western hairstyles and fashion and the Gregorian calendar, as well as overhauling the education system, which sent many Japanese overseas to study and also employed Westerners to teach in Japan.

The political system continued to be fine tuned in the years after the restoration, with Japan ultimately choosing a model of government heavily influenced by the Prussian constitutional system resulting in the promulgation of the constitution in 1889—a system that some historians argue never ceded enough power to parliament, such that the fledgling democracy was unable to counter the growing militarism of the 1930s.

How does the Meiji Restoration relate to Japan’s expansionism and World War II?

Being a modern country in the 19th century also meant having an empire. Japan, after all, wanted to free itself from its weak Asian neighbors like Korea and China, to join the ranks of the world’s imperial powers. It was a project that the men behind the Meiji Restoration, who themselves hailed from the pre-modern samurai ranks, firmly believed in.

In emulation of Western imperialist policies, Japan would go on to defeat the Chinese Qing Empire in 1894 and in the following year gain control of Taiwan and the Liaodong Peninsula in northeast China—a territory it was quickly forced to give up after intervention from Russia and other Western powers, who viewed Japan’s expansionism as a threat to their own ambitions.

That fueled a concerted military build-up by Japan, which eventually defeated Russia in battle in 1905 in northeast Asia, a victory that signaled to the world that Japan could stand shoulder to shoulder with the West. With Russian influence effectively eliminated from the region, Japan was also able to take control of Korea in 1910.

Japan’s imperial successes fueled the idea of a pan-Asian ideology, where Japan would lead the region into civilization. Pan-Asianism initially elicited support from Asian figures preoccupied with shaking off the yoke of Western imperialism, including Sun Yat-sen, the father of the Chinese republic.

It sounds like commemorating the Meiji Restoration got a whole lot more complicated.

It did. As Nick Kapur, a Japanese historian at Rutgers University, noted, the centenary celebration of the event in 1968—just two decades after the end of World War II—was deeply controversial.

“A lot of people objected to celebrating it because they felt that the government’s view of the Meiji Restoration was too rosy, and ignored World War Two and all the suffering that people had endured,” said Kapur. “[They thought that] maybe the Meiji constitution led directly to militarism because it was poorly written… Maybe it was something to reflect on more seriously, rather than just saying, ‘wow Japan’s so great.'”

How is it being remembered in 2018?

Prime minister Shinzo Abe—a fervent nationalist—has invoked the revolutionary and regenerative power of the Meiji to exhort the people of Japan to remember the spirit of that era in order to overcome the crises facing the country today.

“Much like our predecessors in the Meiji Era, we will again create opportunities for all Japanese people and thereby surely surmount the issue of the rapidly aging society and decreasing birthrate,” said Abe in a January speech to the Diet. “Now is precisely the time for us to create a new Japan.”

Daniel Poch, an assistant professor in Japanese studies at the University of Hong Kong, said that under Abe’s government there is an attempt to undo, to some extent, the post-war constitution’s attempt to de-emphasize the sacredness of the emperor “and instead go back more to the Meiji idea of a strong, nationalist Japan.”

Yet the celebrations this year have been curiously muted, with events commemorating the Meiji Restoration’s 150th anniversary largely falling to the regions, rather than being coordinated in a concentrated way at the national level.

The most vibrant of these celebrations are taking place in Kagoshima in Kyushu, the birthplace of the key players behind the Meiji Restoration. That suggests that long after the war has ended, a new set of difficulties qualify any celebratory mood. Barack Kushner, a historian of Japan at Cambridge University, offered two reasons why on a recent program on the BBC World Service: that Japan at 150 years post modernization is an elderly society, and the geopolitical configurations of the region in 2018 are vastly different than in 1868.

“I think the irony of celebrating Meiji in this century is that Japan… is facing a whole new set of problems—a drastically aging society [while] looking forward with great fear at the rise of China,” said Kushner. ”Japan is struggling with its place in east Asia. I do wonder if this lack of celebration, or more [of them] on a national level, is because the Japanese are floundering themselves with how to talk about the Meiji Restoration.”

Abe is set to deliver a speech on Oct. 23. Some analysts suggest that the date—coming just before a planned meeting with him and Chinese president Xi Jinping in Beijing—could complicate relations between the two countries, as the Chinese may remember the Meiji era as the time when Japan defeated China in battle and embarked on its colonization of Asia.