The clean-up crew at RBS is doing the bare minimum to detoxify the bank

By most definitions, RBS is a bad bank. Today it made it official.

By most definitions, RBS is a bad bank. Today it made it official.

The lender, 81%-owned by the British government, reported a third-quarter loss of £828 million ($1.3 billion), but that was hardly the biggest news of the day. Some influential policymakers wanted to see the bank split up, moving its most toxic assets into a state-owned vehicle so that a leaner, cleaner RBS could return to something resembling normality.

In the end, RBS announced the creation of an internal “bad bank“ to house £38 billion of its riskiest assets, which it will try to offload over the next three years. The move will generate a “substantial” loss for the bank this year, it said. The third quarter’s loss takes the bank’s cumulative losses since 2011 to £8.5 billion. The government spent £45.5 billion to bailout the bank in 2008.

This approach stops short of full separation, and represents a fairly subtle rebranding of RBS’s “non-core” division, which the bank created in 2009. In a report weighing the options of a bad bank or a break up (pdf), the government parses the differences between a bad bank and a non-core division pretty finely; things like “improved clarity of purpose,” “sharper focus,” “stronger oversight” and “better disclosure” are cited as the key changes from the switch. In essence, RBS did as little as possible to appease its critics.

Breaking up is hard to do

In the government’s report justifying the creation of an internal bad bank, it warns of a protracted fight with the European Commission if it broke RBS up and used taxpayer funds to back the bank’s toxic assets. Still, government finance chief George Osborne says that the state is unlikely to sell down its holding in the bank before the 2015 general election, despite opting for the most expedient option in cleaning up its balance sheet.

In time-honored fashion, the bank’s new chief executive, Ross McEwan, put out plenty of other bad news today, clearing the deck at the start of his tenure. RBS published an independent review of its small-business lending practices, which found that the bank turned away three out of four borrowers that come to the bank. It also acknowledged that authorities have contacted it over the alleged manipulation of foreign exchange rates, suspending some of its traders in response.

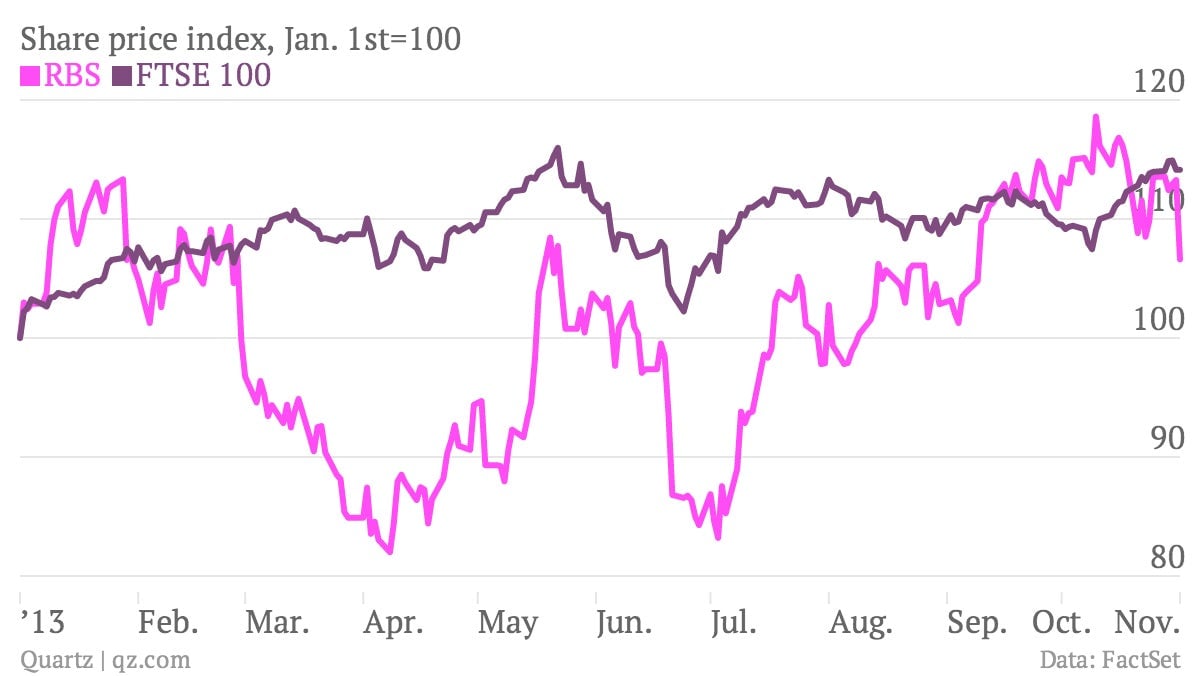

RBS’s shares dropped by more than 5% on today’s news. British taxpayers may have avoided directly funding a toxic asset-laced bank hived off from RBS, but as majority owners of the beleaguered group—both its good and bad parts—in one way or another they remain exposed to the horrors that continue to stalk its balance sheet.