Why are we still arguing for the business value of design?

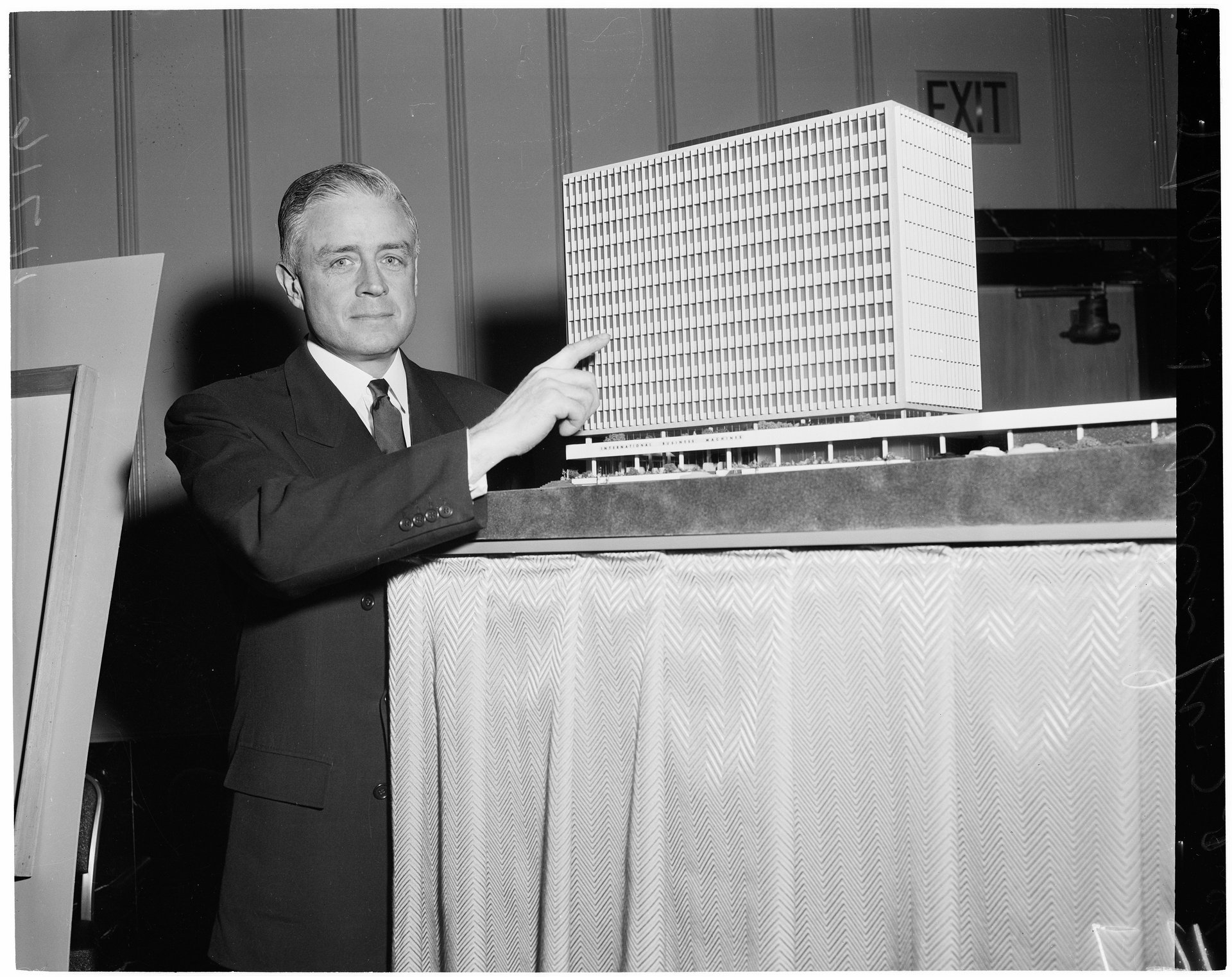

“Good design is good business”: This line from then-IBM president Thomas J. Watson Jr.’s 1973 speech at the University of Pennsylvania has become a battlecry for the place of design in business operations.

“Good design is good business”: This line from then-IBM president Thomas J. Watson Jr.’s 1973 speech at the University of Pennsylvania has become a battlecry for the place of design in business operations.

Watson Jr., who fell in love with modern design in an Olivetti typewriter showroom, is remembered as the most ardent corporate champion for visual arts of his time. During his tenure, IBM leaned on a roster of architects and designers—Charles and Ray Eames, Eero Saarinen, Paul Rand, Isamu Noguchi—and established itself as a design-forward company. With the help of MoMA curator Eliot Noyes, IBM transformed its image from a company that sold meat grinders and punch cards to “the paradigm of the modern corporation,” as design historian Steve Heller puts it. Through corporate branding, stylish corporate offices, product packaging, and World Fair pavilions, IBM became a locus of innovation and good taste.

In more recent years, the idea that design can make a company was propagated by Steve Jobs, who also incidentally employed some of the designers who worked for IBM. Apple’s incredible success during his tenure convinced the world about design’s efficacy.

“Only a decade ago, senior business executives tended to dismiss design as a second-tier function—a matter of aesthetics or corporate image best left to the folks in marketing or public relations. No more,” writes Clay Chandler in Time. ”Today design is widely acknowledged as a C-suite concern and a key element of corporate strategy.” Indeed, many top organizations have a chief design officer, and Apple, 3M, Johnson & Johnson, McKinsey, Pepsi Whirlpool, even the city of Los Angeles, have a design expert in their executive ranks. In a 2017 seminar, Adobe’s executive creative director Steve Gustavson argued that 50% of companies Adobe surveyed attest that “design plays a huge role in how they achieve success.”

Forty-five years after Watson Jr.’s address, most companies understand—or at least have an inkling—that design is integral to business. Despite that, designers and conference organizers haven’t given up the familiar slogans about its business value.

Conferences, papers, books, and think pieces take on the topic with exhausting regularity: There’s the Design Management Institute’s The Value of Design, Design Council annual survey about value of design in the UK; frog’s 2017 paper “The Business Value of Design” the Design in Tech report; and the forthcoming McKinsey initiative that quantifies the financial value of design to businesses.

It makes one wonder why design needs to be constantly justified. Why is design still introduced with caveats like this one from the 2017 Design in Tech report: “Design isn’t just about beauty; it’s about market relevance and meaningful results.” Have designers not sufficiently convinced the world of their work’s strategic value after all?

The era of design slogans

In five short words, Watson crystallized what design could offer business. But a more fundamental question remains unsettled.

“What is design?,” remains a favorite topic of many industry gatherings. Google’s Design is […] series, for instance, is framed as a search for a definition for the apparently undefinable trade. (Imagine if doctors gathered to discuss “What is medicine” or bakers met to unpack “What is bread”?)

Many answers reflect the style of Watson’s pithy proclamation: “Design is thinking made visual (Saul Bass);” “Design has nothing to do with art” (Milton Glaser); “Design is how it works” (Steve Jobs).

But these beautifully phrased statements (often accompanied by beautiful posters) don’t do much to explain how design works, or what good design looks like. The tired joke is still that no one understands exactly what designers do all day.

The matter has been complicated by the rise of the alluring, but oft-misunderstood term, “design thinking.” For better or worse, many organizations now require some kind of designer-led co-creation process in their methodology. Several US government agencies including the US military, have endorsed or required ”human centered design” in its programs.

“The rise of IDEO and the popularity of ‘design thinking’ as a business strategy has tended to conflate what used to be a specific craft skill to the level of vague and generalized management theory,” observes Pentagram partner Michael Bierut. “All of this is happening in an environment where machine learning and AI promise or threaten to turn what used to be expert design decisions into an endless and perpetual series of instantaneous A/B tests.” In reality, these Post-It heavy pow-wows often result in interesting conversations that never materialize in the actual product.

Many organizations seem to have bought into the idea that design is important, but they do not necessarily understand why.

The pitch evolves

The most interesting conversations about design today have moved past extolling the importance of good design (we get it). They instead focus on what we mean, exactly, when we say “good design” and how we can achieve it in a particular context.

IBM’s VP of design Doug Powell says he sees signs that we’re finally shedding catch phrases and the romantic idea of the lone design genius. Compared to five years ago, when IBM spent a considerable time explaining “what design is” with every new client, the focus today is more on how to make it happen. Powell also points to the clamor for forums like the DesignOps Summit, which, as its name suggests, is “dedicated to showing design leaders how to create design capacity. ”We’re past the era of sloganeering,” he tells Quartz.

He adds that while Watson Jr. was primarily concerned with using design and big-name designers to create a modern brand half a century ago, IBM’s latest “design renaissance” positions design as a tool to generate effective, empathetic solutions. Put another way, enlightened organizations have stopped fetishizing designers as artists to call upon to make things pretty at the end of a process.

Yale lecturer Jessica Helfand, who is co-organizing The Design of Business | The Business of Design conference with Bierut, points to an often overlooked nuance in Watson’s famous maxim. “Watson was terrific—prescient, even—and the essay is canonical, not because it presaged design’s value in commerce but because at its core he made such a humane argument,” she explains. “[Good design is good business] points equally, if not more, to the idea of character, period. As in, having one. Behaving with integrity. Standing up to bullshit. In an age in which veracity is itself under constant attack, why can’t design reassert its power and purpose as a conveyor of truth, of clarity of purpose, of honest intent?…Wouldn’t it be something to return to the ‘goodness’ embedded in Watson’s title by reconsidering design as the humanist discipline it always was?”

Bierut says arguing for the business value of design today needs to involve “ethics, purposefulness, and the idea that design can make the world a better place”—something often overlooked, as evidenced by the recent breaches in the tech sector. “What is needed now is not a more convincing case about the value of design,” he explains, “[What’s needed is] more deep thinking about for whom that value is meant to benefit.”