This tiny fish is scarfing down your plastic trash

There’s more plastic floating around the ocean than any other type of marine debris—that we know. What’s harder to figure out is just how much is out there. A recent survey of marine plastic debris found something surprising: Nearly 99% of it was missing.

There’s more plastic floating around the ocean than any other type of marine debris—that we know. What’s harder to figure out is just how much is out there. A recent survey of marine plastic debris found something surprising: Nearly 99% of it was missing.

“We were expecting values in excess of one million tonnes [1.1 million tons] of plastic, and only found between [10,000] and 30,000 tonnes [11,000-33,000 tons] of plastic,” Carlos Duarte, director of the University of Western Australia Oceans Institute, recently said in a presentation. ”This doesn’t mean plastic isn’t being produced and released, it means plastic is being lost somewhere.”

Where might it have gone? A lot of it’s going into the stomachs of a lanternfish, according to Duarte’s presentation (the discussion of the lanternfish starts at about 32:00):

Much of the missing plastic is small debris of a size resembling small organisms called zooplankton. This squares with past research showing that lanternfish had been chowing down pretty heavily on smaller chunks of plastic debris. A 2008 study published in Marine Pollution Bulletin found around 35% of fish specimens with plastic in their stomachs. Though on average they consumed two pieces of plastic, one lanternfish had gorged on 83 chunks.

How could such a tiny fish put away hundreds of thousands of tons of plastic? For one thing, their populations are massive, making up a minimum of 50-60% of deep sea fish biomass.

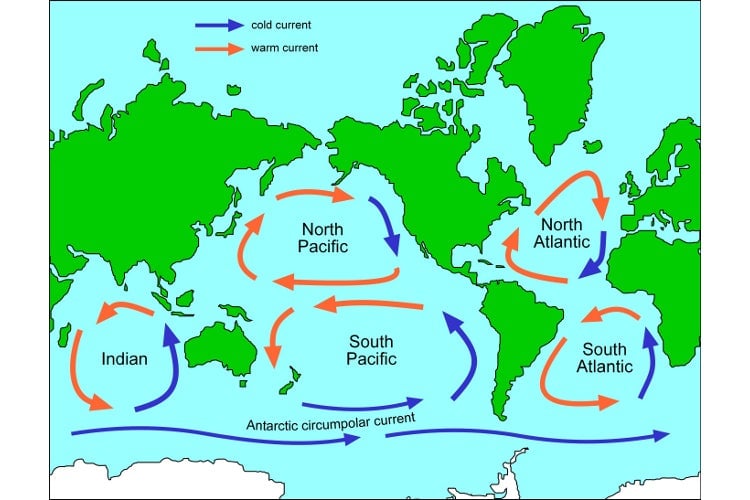

Lanternfish also abound in the five gyres of the ocean, meaning huge pools of stagnant water where plastic typically accumulates. During the day, lanternfish live at depths between 300 meters (980 feet) and 1,500 meters (4,900 feet). But as sundown approaches, to evade predators and feed on zooplankton, they swim toward the surface. That’s the largest migratory movement on earth, says Duarte, and it happens every day.

Little is known about the world’s five gyres. Only one—the North Pacific Ocean Subtropical Gyre, which some say is double the size of Texas—has been well studied. Research last year showed a 100-fold increase in the volume of plastic debris in the “Great Pacific Garbage Patch,” as it’s known, in just 40 years.

So tiny fish are eating all our litter. Does that mean it’s okay to stop recycling?

Probably not. These little guys are a critical food source for dozens of species, including salmon, tuna, squid and other human favorites. It’s not clear whether the lanternfish are actually able to excrete or regurgitate their plastic snacks (pdf), according to a 2008 study in the Marine Pollution Bulletin. And even if they are passing trash, plastic toxins may be permeating their tissue. So chemical remnants of your discarded yogurt tub may be winding up in your sushi.

Another worry about the lanternfish’s plastic habit is the lack of nutrition, which could eventually starve them. And because they’re one of the basic buffet items of the marine food chain, a drop in their population could crater the global fish population, said the MPB study.