In China, retail isn’t dead. It’s just getting started

Consider Alibaba, the Chinese internet giant whose wide-ranging businesses span e-commerce, offline retail, fintech, online video, maps and browsers, and artificial intelligence. By the third quarter of 2017, Alibaba’s business model appeared to have reached peak fruition, as the company took pole position as the world’s largest e-commerce platform (by a factor of at least double Amazon), but was also third in digital advertising, just behind Google and Facebook. What could possibly change?

Consider Alibaba, the Chinese internet giant whose wide-ranging businesses span e-commerce, offline retail, fintech, online video, maps and browsers, and artificial intelligence. By the third quarter of 2017, Alibaba’s business model appeared to have reached peak fruition, as the company took pole position as the world’s largest e-commerce platform (by a factor of at least double Amazon), but was also third in digital advertising, just behind Google and Facebook. What could possibly change?

Experiments in retail

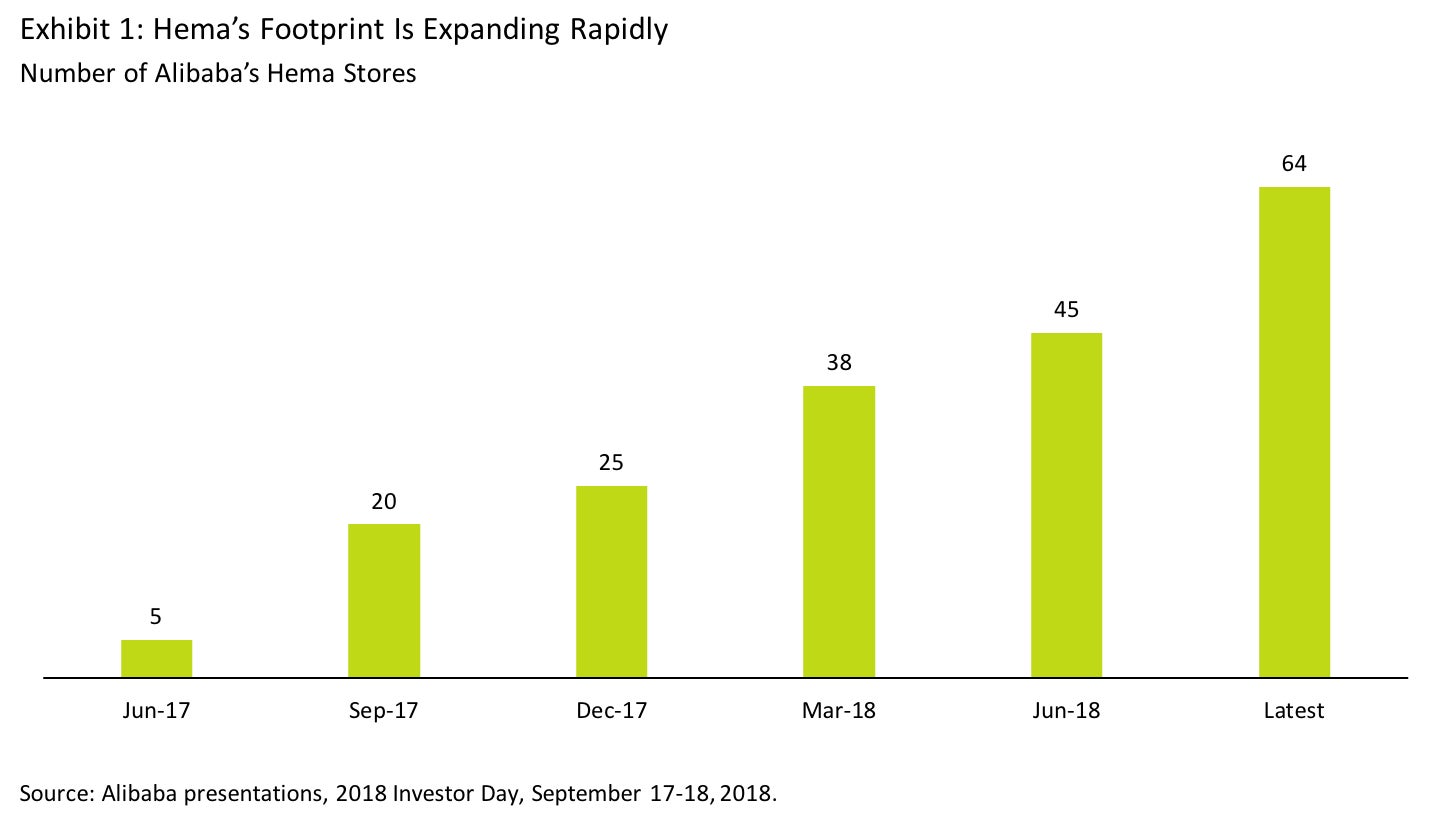

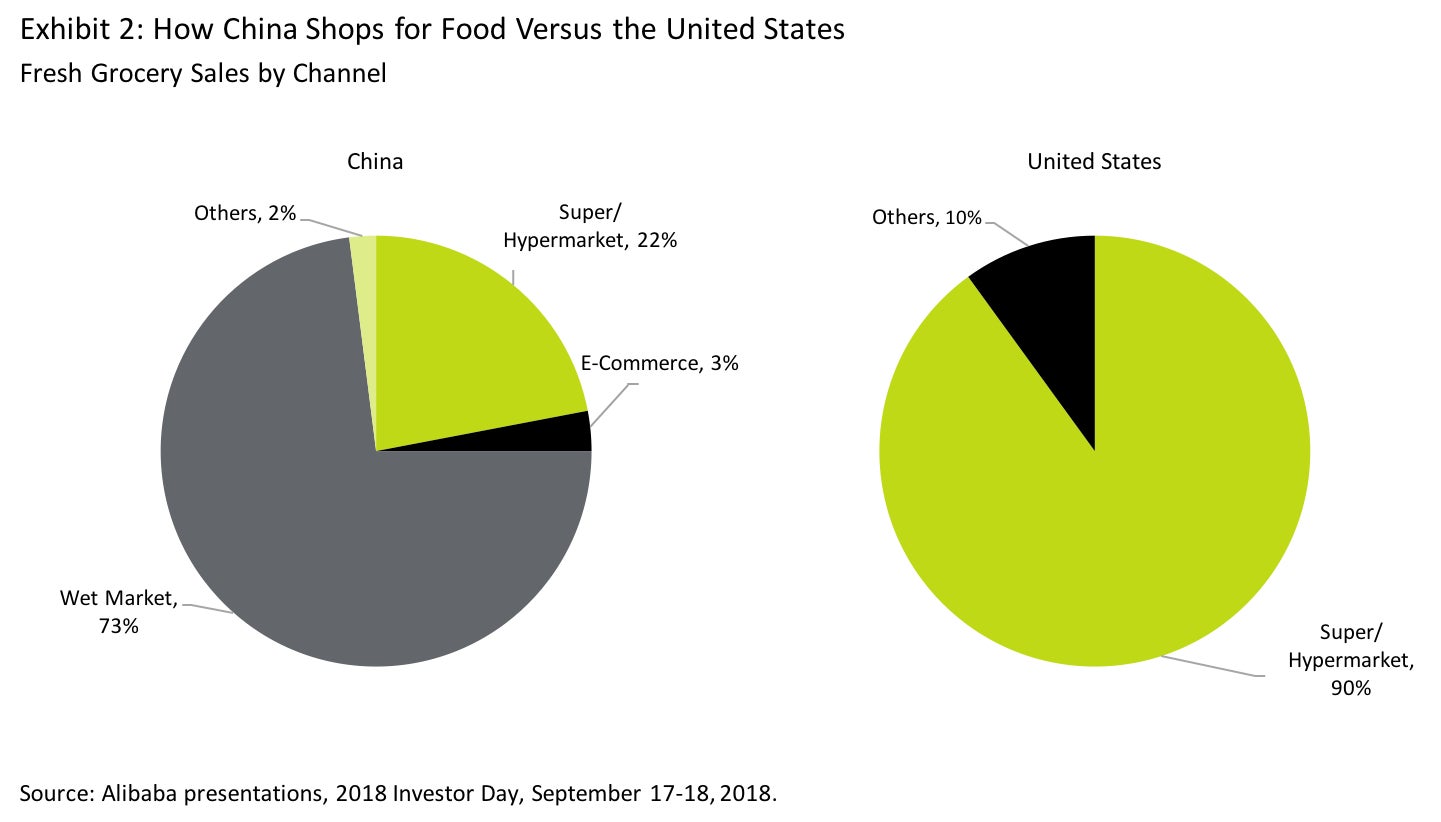

Unsurprisingly, China seems uniquely ready to adopt the Hema concept. Organized channels for buying groceries are currently underdeveloped compared with the United States, where over 90% of grocery already passes through established super/hypermarkets. In China, wet markets, the Asian equivalent of farmers markets that sell fresh meat and produce, still account for more than 70% of the country’s grocery sector. This signifies the boundless potential for Hema as it keeps on driving the new retail experience involving online and offline integration.

There is more. Alibaba’s online shopping Taobao platform is no longer content with making ad-based recommendations, which were driven by keyword bidding by merchants. Recommendation feeds driven by consumer opinions have gained priority, as have sharing, short-form videos, and live streams. Taobao claims a 58% improvement in conversions when users view short-form videos. Additionally, gross merchandise value (GMV) driven by live streaming rose nearly four times in the past year. [1]

Ambitions are also rising at the recently acquired Ele.me, an online food delivery platform. Not content with its 167 million user base, Ele.me is now eyeing the nearly 600 million e-commerce user base of Taobao and Tmall, another Alibaba e-commerce platform, and the 870 million users of Alipay, Alibaba’s digital payments platform, to substantially expand its reach. [2]

Retail space owned by Intime Retail—now a part of Alibaba—is being used for experimental “Tmall pop-up stores,” which allow consumers to walk in, sample inventory, access a large apparel collection on giant touch screens within the store, pay with Alipay, and choose self-pickup or home delivery. Alibaba also has a furniture store that uses augmented and virtual reality to show consumers how an item will look in their homes. And retail stores owned by Sun Art Retail, in which Alibaba has a 31% stake, are dedicating space to products directly sourced from Tmall. These products can be sampled with an eye to the online purchasing habits of people in the immediate vicinity of the store—tastes the offline store may not have been aware of before, but known to Alibaba via its ecommerce operations. Greasing the wheels of this transformation is a planned logistics investment of $15 billion over five years. [3]

The need for a retail transformation

Is there a method to this cornucopia of initiatives? Alibaba’s new long-term target to transition from working with 10 million small and medium enterprises (SMEs) to 10 million profitable SMEs provides a clue. [1] As e-commerce penetration rises to nearly 20% in China, [2] the existing silos of offline and online retail raise vital questions: Are brands and merchants more profitable, or less, as e-commerce grows larger? Does Alibaba’s rising “take rate”—the percentage of GMV that flows into revenues—come at the expense of its merchants’ profitability, or is everyone truly better off? Do merchants enjoy better profitability even as Alibaba raises its own monetization?

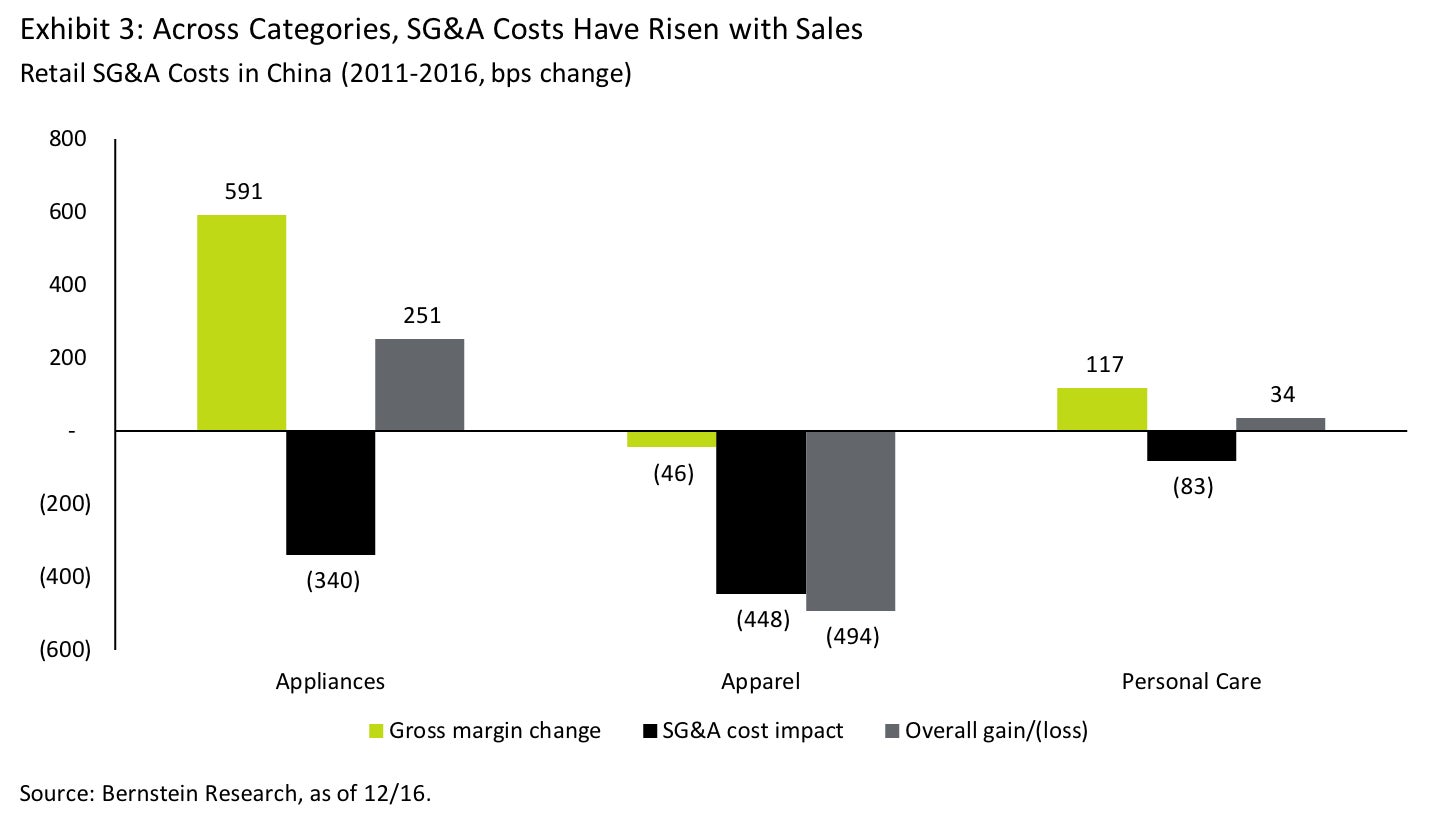

These questions create a fundamental need to transform the way retail works. Analysis suggests that between 2011 and 2016—when e-commerce grew dramatically in China—selling, general, and administrative (SG&A) costs rose significantly for several retail categories as they tried to keep up. Specifically, consumer appliances saw their SG&A costs rise 340 basis points, apparel saw a near 500 basis point rise, and personal care spent 80 basis points more. [3] These rising costs reflect the parallel universes that exist today; offline retail channels, demand management, space planning, supply chains, and consumer analytics have little in common with e-commerce. Increasingly, brands and merchants seem to be running two businesses for the same product, which unsurprisingly leads to cost inflation.

The true promise of omnichannel retail, or new retail, is a more profitable merchant. The future economics of giant e-commerce platforms will likely emerge from this promise, and the hope that these platforms will not simply maintain their share of a shrinking pie, but maintain or increase their share of an expanding one. Not content to be appropriators or gatekeepers of consumer demand, these platforms increasingly aim to help fundamentally change the way consumers shop.

Points of friction are likely

Not all will be smooth, of course. The real world possesses far more points of friction than online businesses traditionally encounter. Offline or omnichannel initiatives address a target market that is five times larger than online retail, but one-fifth as profitable, or even less so in the initial years. [4] Even as the strategic rationale for ongoing initiatives is inescapable, reported profitability is likely to head downward and stay volatile. Indeed, fundamental questions linger. What shall we consider GMV in an omnichannel world? Will walking into a Hema store be considered “offline,” while ordering the same food via the app be considered “online”?

Elsewhere, the expectations of consumers and merchants will remain fluid, exposing new threats and opportunities. Consider Pinduoduo (PDD). Founded in 2015, PDD has grown quickly to become China’s third largest e-commerce platform and has attracted 344 million annual active buyers to its unique model of social commerce, a group-buying model that weaponizes social networks such as Tencent’s WeChat to propagate offers. PDD’s rise offers inescapable proof that there are still unmet consumer needs, despite everything we have already seen in China. And merchants need more too—more analytics, higher returns on their ad spends, and more hand holding with their supply chain and IT systems. There are companies seeking to address these needs: Meituan, for example, is not just China’s largest food delivery and restaurant booking platform, it also provides restaurant management software that is helping to cement its lead.

And thus, to the future of retail. What drives shopping? Needs, of course, but also habits, impulses and, increasingly, fun. Shoppers seek convenience, price, and experience, but also identity and social connection. In the future, will it really matter where we notice a product, where we try it, pay for it, or how it is delivered to us? These ideas are not new, but as e-commerce platforms and offline retail move into each other’s turf, they have acquired an immediacy not seen before. Theory is moving into financial forecasts, and extant silos of thought are beginning to be challenged—just earlier, and faster, in China.

Discover the global trends that could drive growth for investors.

Learn more about Oppenheimer Global Investing.

1. Source: Alibaba presentations, 2018 Investor Day, Sep 17-18, 2018.

Oppenheimer Developing Markets Fund top 10 stock holdings by issuer

All holdings are as of 8/31/18, and subject to change

This article was produced by OppenheimerFunds and not by the Quartz editorial staff.

Foreign investments may be volatile and involve additional expenses and special risks, including currency fluctuations, foreign taxes, regulatory and geopolitical risks. Investments in securities of growth companies may be volatile. Emerging and developing market investments may be especially volatile. Eurozone investments may be subject to volatility and liquidity issues. Investing significantly in a particular region, industry, sector or issuer may increase volatility and risk.

The mention of specific companies or sectors does not constitute a recommendation on behalf of any fund or OppenheimerFunds, Inc.

Carefully consider fund investment objectives, risks, charges, and expenses. Visit oppenheimerfunds.com or call your advisor for a prospectus with this and other fund information. Read it carefully before investing.

These views represent the opinions of OppenheimerFunds, Inc. and are not intended as investment advice or to predict or depict the performance of any investment. These views are as of the publication date, and are subject to change based on subsequent developments.

OppenheimerFunds is not affiliated with Quartz.

© 2018 OppenheimerFunds Distributor, Inc.