Your friends’ voting history and party are public. This app will show you

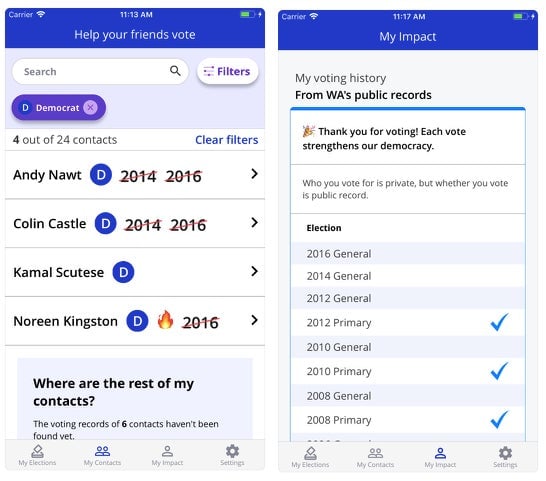

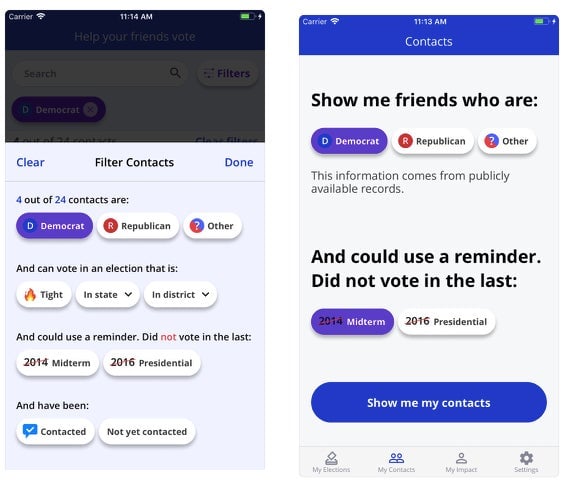

A few weeks ago, I sat down to dinner with my family and opened the VoteWithMe app. Each of my relatives’ names was listed on the screen. Next to each one was a symbol signifying their party registration: Democrat, Republican, or Other. Below that was a long list of elections since 2000 with checkmarks indicating whether they cast a ballot in each one. Before anyone could object, I went around the table as I asked about their voting history (if not who they voted for) in public for the first time.

A few weeks ago, I sat down to dinner with my family and opened the VoteWithMe app. Each of my relatives’ names was listed on the screen. Next to each one was a symbol signifying their party registration: Democrat, Republican, or Other. Below that was a long list of elections since 2000 with checkmarks indicating whether they cast a ballot in each one. Before anyone could object, I went around the table as I asked about their voting history (if not who they voted for) in public for the first time.

My dad, a lifelong Republican now voting Democrat after Trump’s takeover of the GOP, had missed just one poll since 2000, according to VoteWithMe. My stepmother had missed none. That’s true, they confirmed. I turned to another close relative. The app showed she had voted just once in the past 20 years since becoming old enough to do so. “Yes,” she said, wincing. “I’m part of the problem!” But she vowed to vote again this year, her second ballot since 2016.

That’s precisely the kind of reaction Mikey Dickerson envisioned for VoteWithMe, an app drawing on public voting records to show whether friends and family in your contact list are participating in America’s democracy. The way it works is simple. Everyone’s party registration and voting history are a matter of public record. While each state has different rules about accessing this data, companies aggregate and sell voter profiles to campaigns, political parties, and advocacy groups. Similar to the way Zillow made once-obscure real estate prices and history available for anyone to browse, VoteWithMe is making voting records easily accessible to the public for the first time.

The app is the focus for Dickerson, founder of the progressive political nonprofit New Data Project. A former Google engineer, he led the US Digital Service under president Barack Obama and oversaw the healthcare.gov rescue effort. After looking at the data from the Democrat’s 2016 wipeout, Dickerson wanted to retire campaign tactics that weren’t working.

“We found that in 2016, the effectiveness of the things we usually do—door-to-door canvassing, phone banking—was basically gone,” says Dickerson.

Those methods, even during normal elections, might eke out a tiny increase in turnout, or not at all, according to Yale University’s Institution for Social and Policy Studies. Several campaigners in the 2016 election said such efforts may have even backfired as Clinton supporters galvanized Trump supporters to vote by knocking on the wrong doors or calling them at home.

What does work? Personal messages. “We don’t listen to strangers,” he says. “We still listen to friends.”

Dickerson says VoteWithMe’s magic happens after you give access to your contact list. Based on the names, phone numbers, and addresses in your contacts, the system makes an educated guess of who on the voting rolls you know.

In my experience, it was strikingly accurate. For hundreds of my contacts, the voting profile appeared to match what I knew about them. After checking with a dozen or so family members and friends, only one was misidentified.

To get people to the polls, a filtering system automatically identifies personal contacts most likely to need a nudge: sporadic voters who might have missed the last election in districts with tight elections (you can choose which political party to screen). Fence-sitters are the ones most likely to be convinced to show up for the polls. A text message integration then helps you auto-fill and send out personalized messages through your phone.

The app doesn’t try to change anyone’s mind. Opinions are usually too hardened for that. A 2017 article in the peer-reviewed American Political Science Review analyzed 49 field experiments to assess the effectiveness of campaigns’ traditional tactics. “We argue that the best estimate of the effects of campaign contact and advertising on Americans’ candidates choices in general elections is zero,” the article concludes.

What campaigns can do is get out the vote. Turnout makes all the difference. As lots of people historically skip midterm elections, the ability to reach a few close friends and persuade them to vote, multiplied by thousands of people, can flip Congressional seats.

There are plenty being contested. The Cook Political Report lists 29 elections for the House of Representative as “toss-ups,” and another 84 as competitive. In any of those elections, a few thousand votes could make the difference. The Democrats need to flip just 24 seats (paywall) to win back control of the House, which would create a new check on Trump’s power and a means of pushing for more transparency in his diplomatic and business dealings.

The most consistent and effective way to boost turnout, argues Donald Green, a political scientist at Columbia University, is through conversations and encouragement from people we trust. Adding the layer of accountability, as VoteWithMe does through displaying public records, makes it even more effective. “It would be big deal if you do it on a grand scale,” Green says.

The rise of texting

That’s exactly what Dickerson plans to do: scale up the conversation with family and friends through one of the last uncrowded digital channels around: texting. Dickerson claims internal experiments of VoteWithMe’s effectiveness during Democrat Conor Lamb’s successful congressional run in Pennsylvania earlier this year showed the app boosted trips to the polls by 2.4%. While that may not sound like much, in a business where tactics that move the needle by just 1% are considered effective, it’s game-changing. Even with the app’s modest number of users (Dickerson wouldn’t specify the exact count), he figures VoteWithMe could deliver hundreds of thousands of votes for the Democrats.

Texting is emerging as a mature political tactic just as the stakes of close elections couldn’t be higher. Republicans have won increasingly close elections, but they disproportionately benefit from gerrymandered districts, barriers to voting, and low turnout among likely Democratic voters, usually younger and less-well-off citizens. Trump’s rise to the White House rested on just 107,000 votes in three states, or 0.01% of the electorate (although he lost the popular vote by 2.9 million votes).

To reverse that edge, a new generation of friend-to-friend texting apps (OutVote, VoterCircle) and services (Relay, Hustle) have been developed. (Opn Sesame provides similar services for conservative candidates.)

This weekend, don’t be surprised to see your mobile phone light up with political entreaties if you’re in the US. It could be from someone you know or a local volunteer eager to have a conversation. Kate Maeder, campaign manager for Eleni Kounalakis, who is running for lieutenant governor of California, says her volunteers use the Hustle platform to text between 500 t0 1,000 likely voters per hour. The service loads text messages for someone to manually send out to likely supporters of candidates.

Only about 10% respond, but Maeder says that’s built up a huge base of enthusiastic women to mobilize voters for Kounalakis. Maeder is so convinced it’s going to work, she dedicated her entire digital budget to it over online ads. Within a few weeks, she said, the campaign had reached more than 1 million women to get out the vote and raise funds.

The window may not last. “Campaigns are really starting to use it in this [election] cycle,” says Maeder. “Frankly, it might not be around forever. By 2020, or 2022 voters might be tired of it.”

Voters quickly grow weary of technological intrusions into their lives. Texting, even when done by people you know, may soon wear out its welcome. Although rules by the US Federal Communications Commission prevent campaigns from sending automated texts, tools that do everything but press the “send” button ensure today’s stream of personal texting will turn into a flood. In 2018 alone, candidates on Hustle’s platform have exchanged 17.5 million messages with voters.