Broken companies may finally escape private equity’s game of hot potato

The listing of theme park operator Merlin Entertainments in London was hardly the biggest IPO news this week. The group that runs Legoland, Madame Tussauds, the London Eye and other theme parks raised £957 million ($1.5 billion) in an IPO on Nov. 8, valuing the company at £3.2 billion. Its shares rose by around 10% on the first day of trading.

The listing of theme park operator Merlin Entertainments in London was hardly the biggest IPO news this week. The group that runs Legoland, Madame Tussauds, the London Eye and other theme parks raised £957 million ($1.5 billion) in an IPO on Nov. 8, valuing the company at £3.2 billion. Its shares rose by around 10% on the first day of trading.

But Merlin’s listing is significant for reasons other than its valuation. The company tried to list in 2010 but gave up when market turbulence and reticent investors depressed its potential valuation. This triggered yet another shuffle in its ownership—few firms have been passed between as many private equity firms over the years as Merlin.

In 1999 senior managers at the company enlisted private equity firm Apax Partners to help finance the initial buyout from its former parent company. Apax then sold its stake to Hermes Private Equity in 2003. Hermes later sold out to Blackstone in 2005, when the company acquired the Legoland theme park business. In 2007, Blackstone acquired the company that runs Madame Tussauds wax museums, which itself had been passed between two financial investors before being sold to Blackstone, and merged it with Merlin. Following the group’s failed listing in 2010, Blackstone sold a portion of its stake to CVC Capital Partners. Got it?

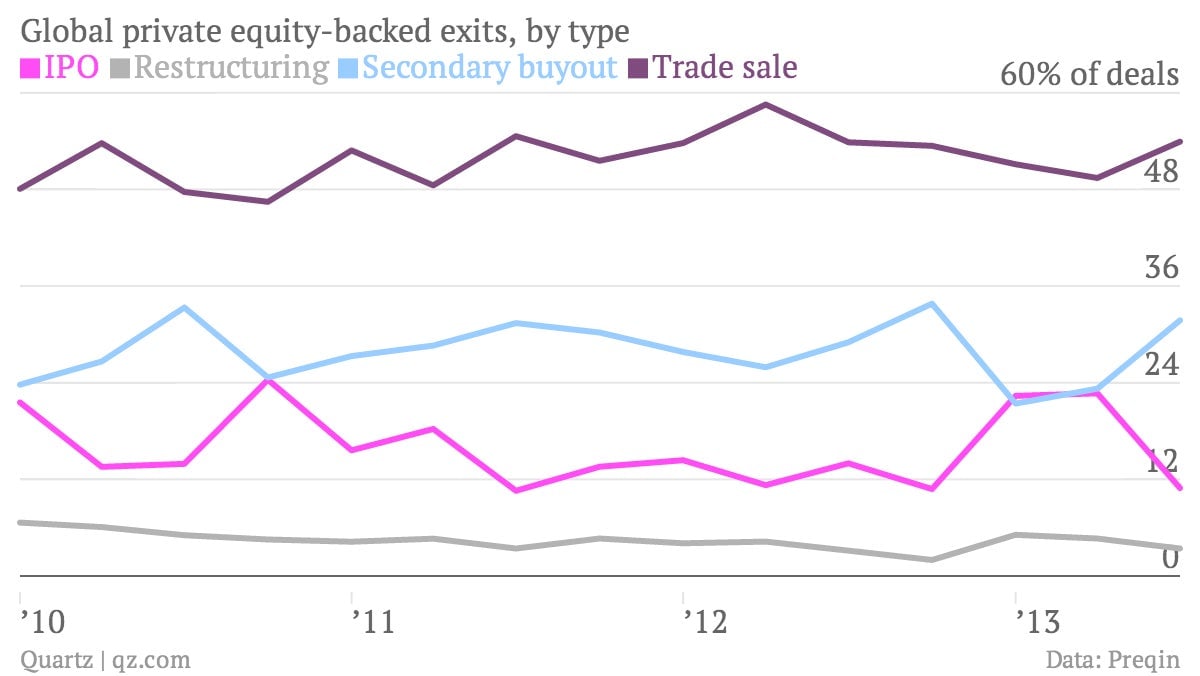

Secondary buyouts—otherwise known as “pass the parcel” deals—are when one private equity firm sells a company to another. Private equity owners typically get better prices by selling to trade buyers or listing companies on the stock market; secondary buyouts sometimes carry a whiff of desperation. PE firms bill themselves as skilled financial engineers, so the prospect of a second or third firm wringing more value out of a company tends to diminish. Secondary buyouts also risk annoying big investors, who are often invested in both the buying and selling of funds, paying transaction fees for simply transferring the same company from one part of its portfolio to another.

Secondary buyouts are particularly popular in Europe, where IPO and M&A markets have been subdued in recent years thanks to the region’s economic turmoil. So far this year, secondary deals have been worth more than primary deals in Europe, which some private equity bosses fret is a bad sign for the industry. Globally, the two biggest buyout deals in the third quarter of this year, for retailer Nieman Marcus and insurance broker Hub International, were both secondary sales.

Merlin’s IPO comes amid a spate of other private equity-backed listings in Europe, giving hope to firms sitting on hard-to-sell investments. To be fair, Merlin’s various secondary (and tertiary) sales have generated decent returns for the selling firms, but given the odds for diminishing returns it will be relieved to finally offload a stake to someone other than another private equity firm. Some analysts are understandably wary of investing in a debt-laden company that has passed through so many private equity owners’ hands. If Merlin’s shares continue to rise it could unlock the market for others like it; if it struggles, the market for post-pass-the-parcel deals could be as lifeless as a wax statue.