A photographer captured the surreal beauty of Hong Kong’s bamboo scaffolding

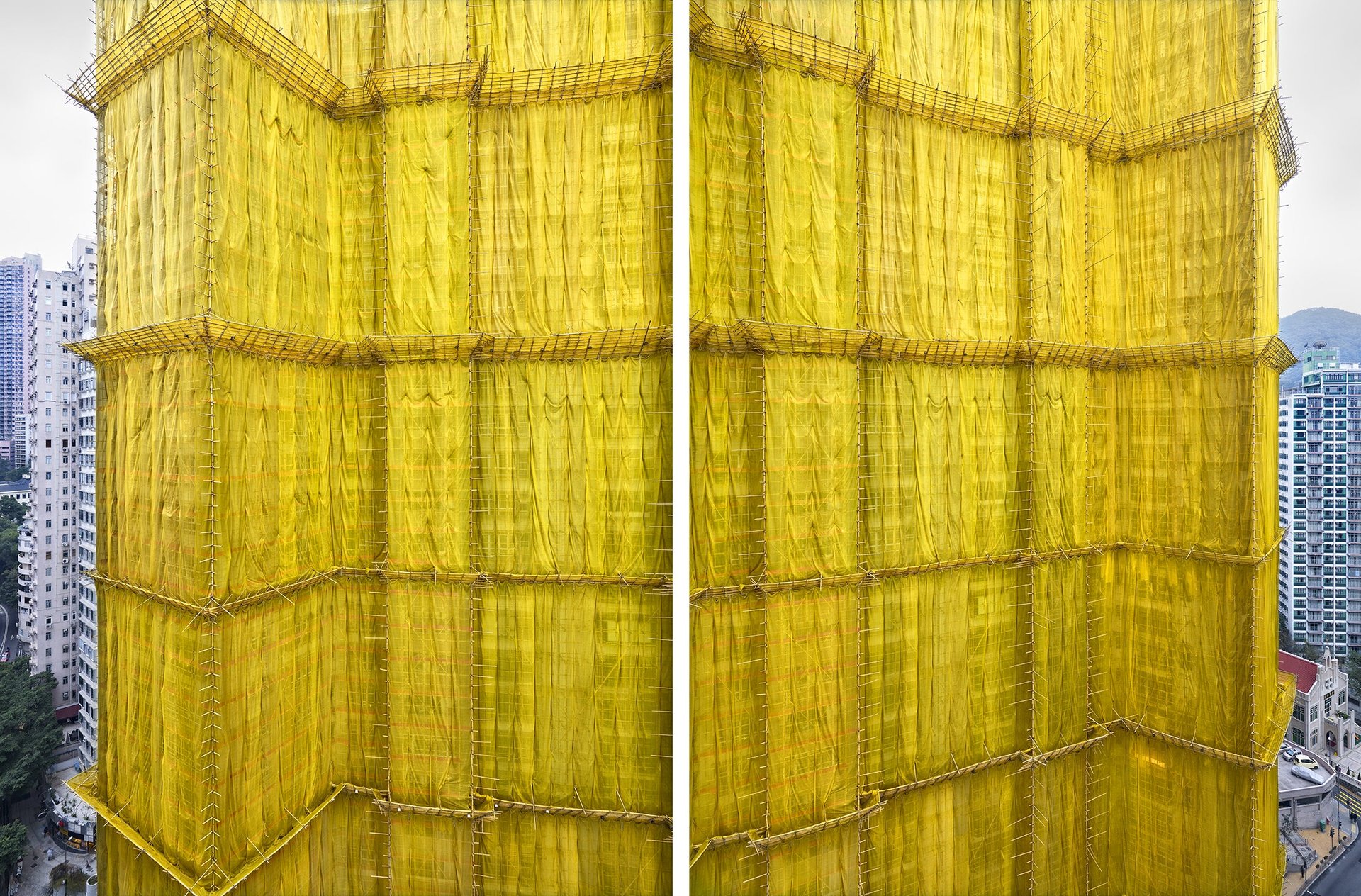

When American photographer Peter Steinhauer first visited Hong Kong in 1994 the sight of skyscrapers wrapped in canvas and skeletons of bamboo evoked the massive public artworks of Christo and Jeanne-Claude. But this wasn’t anything close to an art installation, it was one of the oldest traditional building practices still in use, in a modern city that grows taller and denser every day.

When American photographer Peter Steinhauer first visited Hong Kong in 1994 the sight of skyscrapers wrapped in canvas and skeletons of bamboo evoked the massive public artworks of Christo and Jeanne-Claude. But this wasn’t anything close to an art installation, it was one of the oldest traditional building practices still in use, in a modern city that grows taller and denser every day.

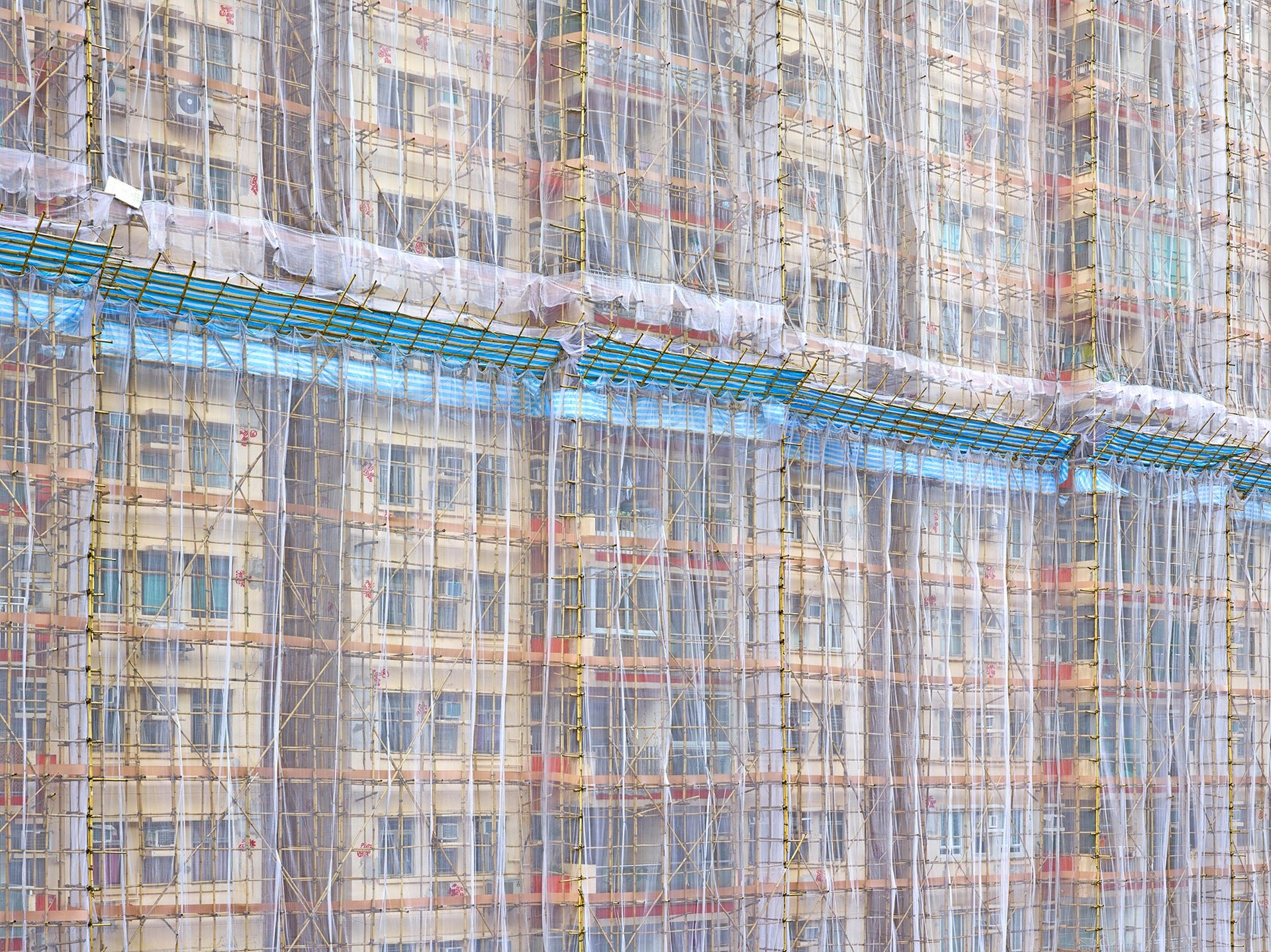

While a style of building that seems more at home in an ancient civilization seems completely antiquated in such a rich and modern city, it is actually perfectly suited for the density and vertical growth of Hong Kong. A 2013 South China Morning Post article noted that bamboo’s lightweight properties allow scaffolding to be erected quickly, usually with few materials other than plastic ties. Since it can be cut easier than metal, the scaffolding can be customized to fit different building shapes and the narrow spaced in between structures:

Compared with iron rods, bamboo rods are cheaper, faster to build, and easier to transport. Despite their appearance, bamboo rods are actually safer, as they are much lighter than iron rods and cause less damage if they fall.

To build bamboo scaffolding, which can be as gigantic as the Four Seasons hotel, it only requires three things: bamboo rods, scissors, and plastic fiber straps. Workers often set up scaffolding in the middle of the night, eight hours at a time.

Overall, the trade is still thriving, with more than 2,800 registered bamboo scaffolders working (pdf) in Hong Kong, up from around 1,700 a decade ago.

Steinhauer’s large format photos heighten the juxtaposition of enormous buildings encased in bamboo and sometimes a veil-like colorful canvas. The canvas, Steinhauer explains in his book, is to catch any falling debris. Buildings under renovation are typically covered with a semi-transparent mesh, while ones being demolished are wrapped in dark green. The buildings, shrouded in their hermetic casing, are the inspiration for his book’s title: Cocoons. “Colored material unveiled ceremoniously revealing a new facade,” he describes, “just like a butterfly uncovering itself for the first time.”