The real reason everyone fears a Spanish debt downgrade

Ratings agency Standard & Poor’s chopped Spain’s credit rating on Oct. 10. Moody’s has been expected to downgrade the country for a while—in its case, to speculative-grade or “junk” status. This wouldn’t exactly surprise investors, since Spain has been in a perpetual state of almost asking for a bailout for the last few months. A downgrade would be nasty for Spain, which would likely face higher borrowing costs and need to offer more collateral in order to borrow.

Ratings agency Standard & Poor’s chopped Spain’s credit rating on Oct. 10. Moody’s has been expected to downgrade the country for a while—in its case, to speculative-grade or “junk” status. This wouldn’t exactly surprise investors, since Spain has been in a perpetual state of almost asking for a bailout for the last few months. A downgrade would be nasty for Spain, which would likely face higher borrowing costs and need to offer more collateral in order to borrow.

However, the downgrade could be far scarier for corporations already suffering from a euro-zone slowdown. We wrote last week about Telefónica’s difficulties funding its own debt, and how the telecom—like other big European corporates—is already selling off pieces of itself to convince investors it can weather economic turmoil. A downgrade of Spain to junk would probably come with a downgrade of Telefónica, and its bonds would become too risky for many investors.

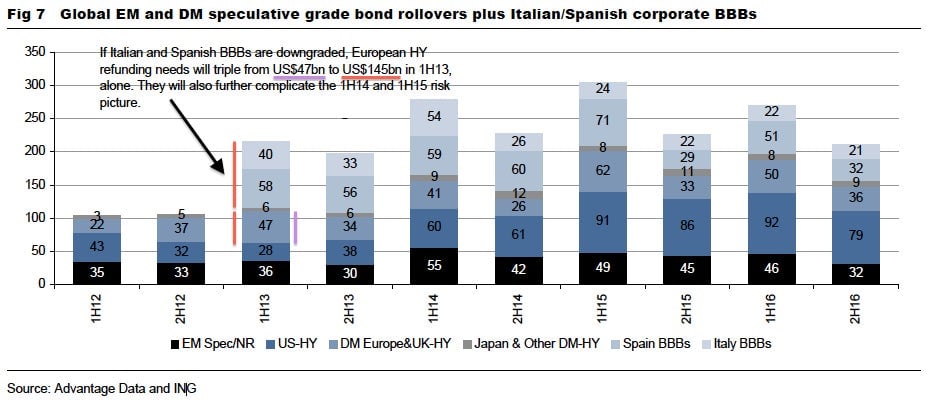

Indeed, that fate could befall many Spanish companies. This would dramatically increase the supply of junk bonds—high-risk and high-yield—in the markets. Corporations would compete harder to get funding and probably have to pay huge sums to borrow. The same trouble goes for Italian corporates, which also teeter on the brink of a speculative-grade credit rating. Should both Italy and Spain be downgraded, writes David Spegel, ING’s global head of emerging markets strategy, “this effectively triples the total amount of high-yield European [debt] due in the first half of 2013 alone.” (see chart above)

Triples. That is a huge burden on the companies, and a huge increase in the amount of risky bonds floating about. That debt will need to be refinanced in the markets… or else.

Well, investors holding the formerly investment-grade bonds of these companies would suddenly be flush with high-risk investments. To manage this risk, they may keep only the least risky bonds. The companies with the lowest credit ratings, finding no buyers for their bonds, could be forced into default as soon as 2014, explains Spegel.

Companies like struggling automaker Fiat could bear the brunt of these moves. The company has already been paying upwards of 7% to borrow for four or five years, and the collapse of European demand for cars means they’re not about to make a lot more money. “It is a question of survival for many manufacturers who are struggling to sustain the same level of capacity as in pre‐crisis times,” Fiat CEO Sergio Marchionne told reporters on October 10.

Thus these companies are under a sword of Damocles, held over their heads by a fragile thread. Without a policy panacea that dramatically improves the economy and hence the prospects for Spanish and Italian corporations, they face the constant prospect of mass downgrades. And that ever-present fear, in turn, may continue to keep investors away from the kinds of investments that would keep the Spanish and Italian economies alive.