The IRS hired private debt collectors who are squeezing poor people and hurricane victims

An IRS program using private debt collectors to handle delinquent tax bills is improperly demanding payment from hurricane victims and squeezing some of the poorest Americans—all the while turning a profit far below industry standards.

An IRS program using private debt collectors to handle delinquent tax bills is improperly demanding payment from hurricane victims and squeezing some of the poorest Americans—all the while turning a profit far below industry standards.

Since April 2017, four debt collection companies have been assigned half a million delinquent taxpayers to contact. So far, they’ve brought in less than 1% of what Congress hopes the program will ultimately generate. Meanwhile, tax experts and the IRS’ own oversight board fear that the targeted taxpayers are being pressured to empty out their savings and take on unnecessary financial risk. The National Taxpayer Advocate, an independent office within the IRS that ensures “every taxpayer is treated fairly,” calls the program ”a serious threat to taxpayer rights.”

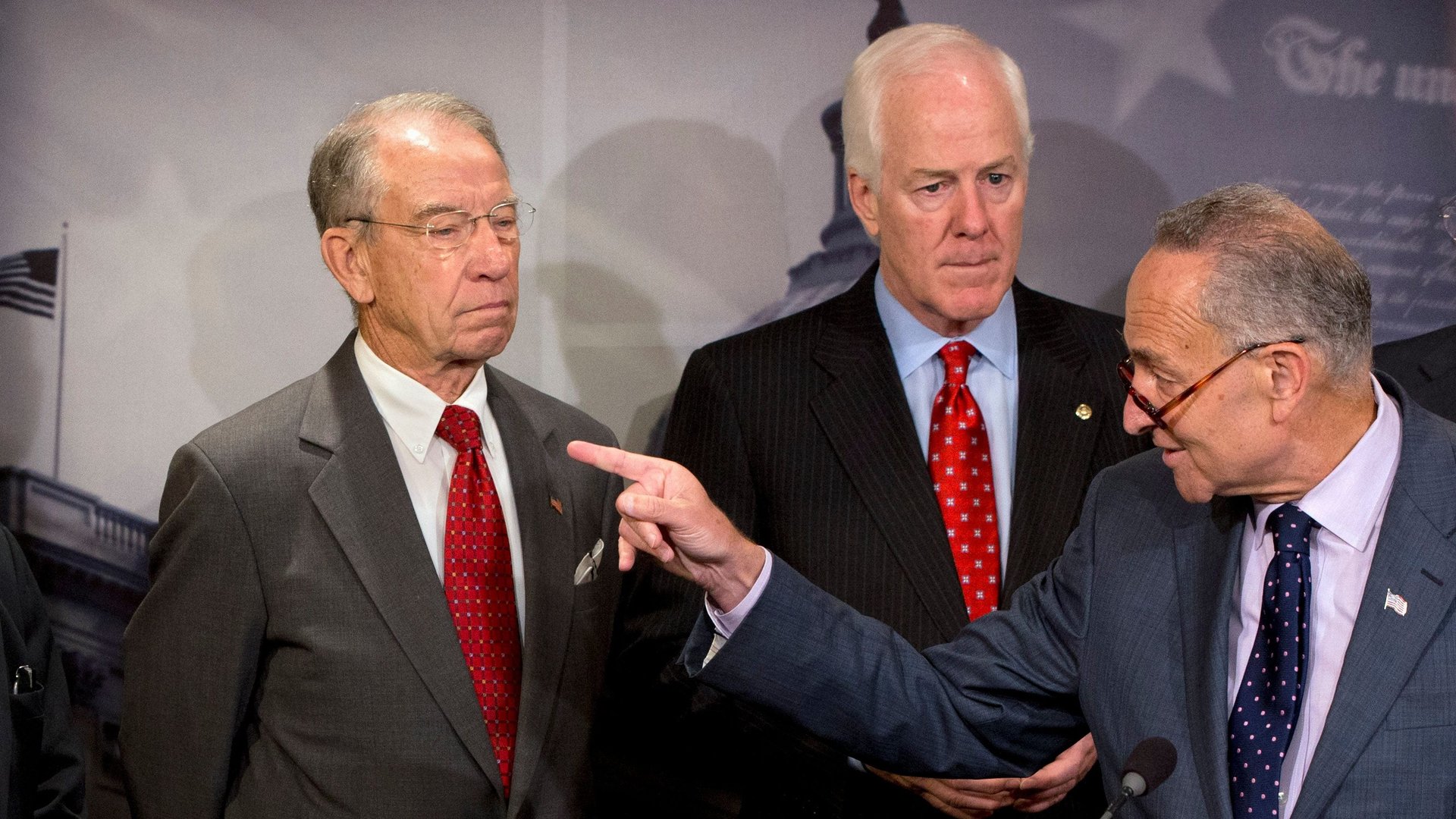

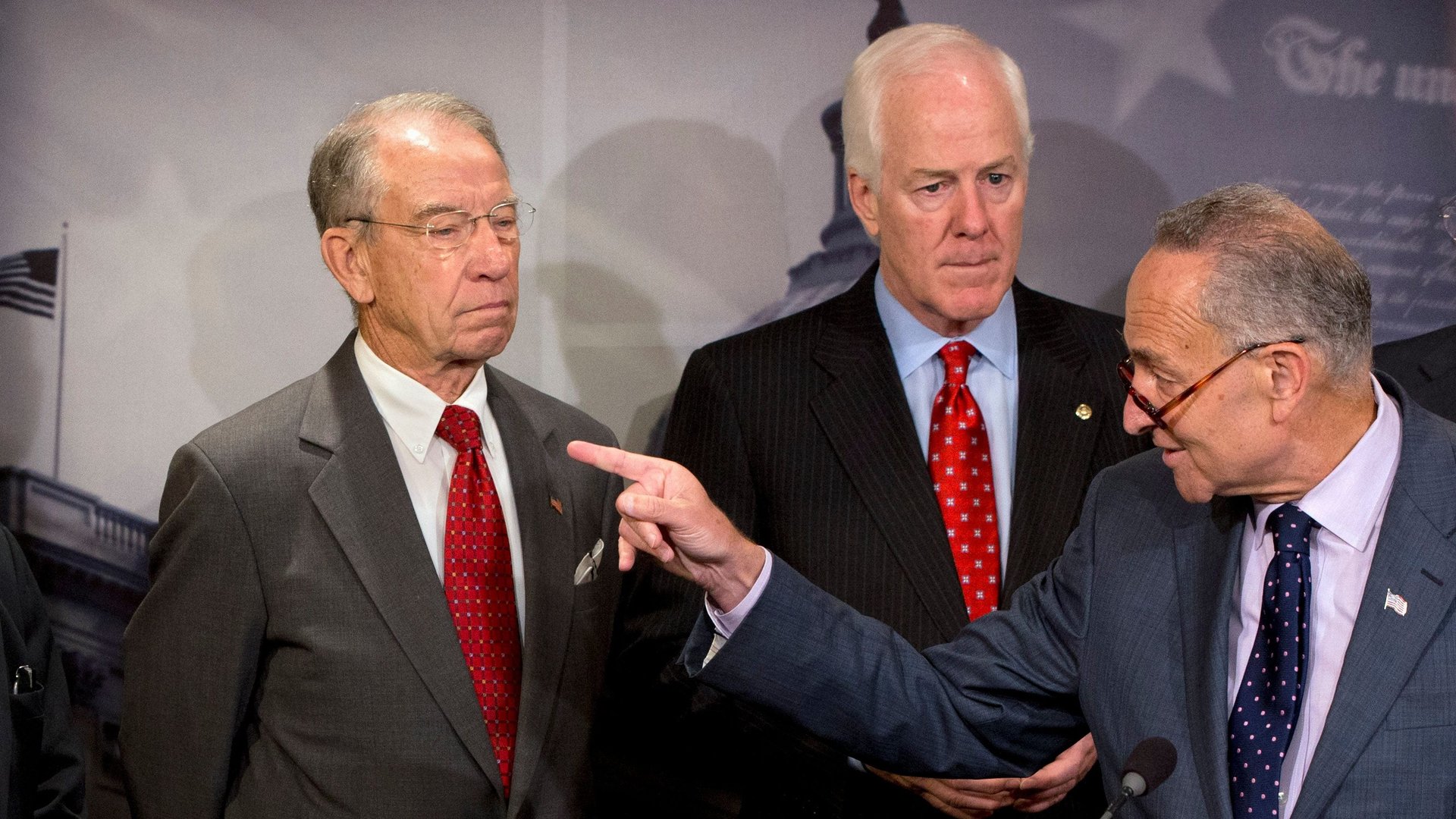

Two US senators pushed the IRS to outsource its debt collection to private companies through this program: Chuck Grassley, a Republican from Iowa, and Chuck Schumer, a Democrat from New York who has hailed the initiative for bringing jobs to one of the poorest parts of his state. As if by coincidence, three of the four debt-collecting companies contracted by the IRS are based in Iowa and New York. They declined to comment on the program.

An ineffective approach

The IRS normally brings in $4 for every $1 put into its budget. But the private collectors don’t appear to be as effective as their government counterparts. From Oct. 2017 to Sept. 2018, the program’s most profitable 12 months, collection companies Pioneer Credit Recovery, ConServe Debt Recovery, Performant Recovery, and CBE Group collected just $2.64 for every $1 the government spent on the program.

The program hasn’t even met the private debt-collection industry’s own financial standards. By June 2018, the companies had recovered just 1% of the of the $4.1 billion in receivables assigned to them, according to a recent report by the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration (TIGTA). The industry average collection rate is 9.9%.

And of the total $88.8 million in revenue that the companies did manage to collect, the IRS only received $22.3 million. That’s because the scheme has cost the US government $66.5 million, between startup costs and commission fees of up to 25%. To reach the Congressional Joint Committee on Taxation’s target of $2.4 billion in total additional revenue by 2025, annual collections need to rise to around 15 times what’s been collected so far, for the next seven years.

The odds are against the hired collectors. After three years, a debt is considered statistically uncollectible—and the accounts the IRS assigned to the private collectors were an average of 3.97 years old, TIGTA reports.

Congress, which forced the scheme upon the IRS, doesn’t seem to have learned much from past failures with private debt collectors. A 1996 pilot program resulted in a net loss of $17 million and was canceled after a year. Another attempt in 2006 led to a net loss of almost $30 million. The most recent available IRS data says the agency is owed more than $131 billion in delinquent payments on 14 million accounts.

Targeting the poor and desperate

Many, though not all, of the accounts the IRS has assigned to private debt collectors involve America’s most vulnerable taxpayers: poor people, and survivors of natural disasters.

Nearly half the people who paid the private debt collectors in the program’s first six months were considered low-income. According to the National Taxpayer Advocate, 19% had incomes below the federal poverty level of $25,000 for a family of four, and 44% had incomes below 250% of the federal poverty level, which the IRS uses to ”identify taxpayers who cannot afford representation in IRS disputes and are therefore vulnerable to overreaching by the IRS.”

The IRS also illegally gave private collectors 2,467 files for taxpayers who were hit by hurricanes Harvey and Irma, the TIGTA report says. Those taxpayers paid a combined $753,465, but they are supposed to be free of IRS collection while they recover from disasters.

Giving such sensitive cases to companies from an industry notorious for riling consumers is “a really toxic combination,” said David Vladeck, a former director of the Federal Trade Commission’s consumer protection bureau and a professor at Georgetown Law. “The incentive to really turn the screws hard is pretty high because that’s the only way they’re going to get paid.”

The IRS did not respond to Quartz’s request for comment.

Turning the screws

By law, the IRS has to make sure taxpayers have enough money to survive on before it demands tax payments from them. In practice, that means leaving debtors up to a few thousand dollars per month to cover basic needs like food, housing, transport, and healthcare. But private collectors “have no obligation or incentive” to inquire about their collection targets’ finances, the report says.

Last year, four Democratic senators accused the contracted firms of illegal business practices. In a letter to Pioneer, the IRS, and the Treasury, the senators said Pioneer, in particular, was acting recklessly by suggesting debtors take on debt or clear out their 401(k) retirement accounts to repay the Treasury.

In 2017, Pioneer was sued by the US government for violating federal consumer financial laws while working on a separate federal government program. The company “systematically misled consumers” while collecting student loan debt for the government, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, an agency created in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, alleges in the suit.

For their part, the four companies say they have no idea whether the people they’re chasing are vulnerable. “[Contractors] do not receive any information about a taxpayer’s level of income and rely solely on voluntary participation by the taxpayer,” Kristin Walter, spokeswoman for the Partnership for Tax Compliance (a coalition representing the four companies), said in an email to Quartz.

“If someone says they can’t pay, even with an extended payment plan, they are removed from the PDC program and their account is referred back to the IRS.” She added that the companies “abide by a stringent set of rules to ensure taxpayer privacy and protection.”

Confusion and scams

For years, the IRS told taxpayers that it will never call taxpayers to demand payment and that anyone saying otherwise is a scammer. It still runs such warnings on its website.

However, the collection agencies working for the IRS do make phone calls. The private collection process begins with a letter from the IRS, which is followed by a letter from the private collections company. Then come the phone calls familiar to anyone that’s ever had an overdue credit-card bill.

This leaves taxpayers exposed to confusion and possible scams. “When you muddy the waters and say you may have to talk to private debt collectors who don’t work for the IRS, it gets harder to discern when it’s a scam,” says Steve Wamhoff, the director of federal tax policy at the Institute of Taxation and Economic Policy, a nonprofit, nonpartisan think tank focused on state and federal tax policy issues.

Beyond just blurring the lines on who to trust, it also opens more opportunities for scammers—who can now pretend they’re from legitimate companies hired by the IRS, says John Wancheck, a senior advisor at the progressive Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a nonpartisan research and fiscal policy institute in Washington, DC.

A bad fix to a self-inflicted problem

The private debt collection program was designed to reinforce the IRS’s tax-collection resources at a time when the agency was strapped for cash, because Congress slashed its budget. The agency’s funding is down 18% in real terms since 2010, forcing it to cut its enforcement staff by a third.

Tax experts say it would be safer and more efficient to direct the entire program budget to the IRS itself. Unlike private collectors, the agency has to abide by stringent checks on taxpayer financial well-being, and it has consistently driven an excellent return on its budget.

“The IRS wouldn’t be hiring collection personnel using scraps salvaged from private profiteering businesses if Congress would do its job and properly fund our most essential government functions, including that of tax collection,” said Mandi Matlock, a tax attorney who does work for the National Consumer Law Center. “Congress created this problem so its friends in private industry could come along and fix it, at a high price to taxpayers.”