Christie’s record auction is actually a gauge for how far the art market has fallen

The very first time the “art world collapsed”—for those keeping track—was the night of Oct. 19, 1973, and it did so “not with a whimper but with a bid.” So wrote critic Barbara Rose a month later in New York magazine, in a scathing takedown of the first widely publicized “record-setting” auction of contemporary art, one conducted by Sotheby’s Parke Bernet on behalf of New York taxi-baron and art collector Robert C. Scull. Perhaps it was the loud cheers that accompanied high bids that night that unnerved her, the “visible action of instant profit-taking”—even the New York Times’ coverage of the evening described an auction “that possessed as much decorum as post-game activities at Shea Stadium”—or perhaps it was the sight of Robert Rauschenberg (whose 1958 combine “Thaw” was sold for $84,100 more than its original $900 purchase price) taking a swing at Scull after the auction and shouting, “I’ve been working my ass off for you to make a profit!” Or it may have been the picket line of furious taxi drivers on Madison Avenue protesting the event, handing out flyers that promised “the unveiling of Robert C. Scull.” Whatever the case, even early observers like Rose saw that the $2.2 million Robert and Ethel Scull took home that night marked a pivotal shift in the relationship between artist, collector and public.

The very first time the “art world collapsed”—for those keeping track—was the night of Oct. 19, 1973, and it did so “not with a whimper but with a bid.” So wrote critic Barbara Rose a month later in New York magazine, in a scathing takedown of the first widely publicized “record-setting” auction of contemporary art, one conducted by Sotheby’s Parke Bernet on behalf of New York taxi-baron and art collector Robert C. Scull. Perhaps it was the loud cheers that accompanied high bids that night that unnerved her, the “visible action of instant profit-taking”—even the New York Times’ coverage of the evening described an auction “that possessed as much decorum as post-game activities at Shea Stadium”—or perhaps it was the sight of Robert Rauschenberg (whose 1958 combine “Thaw” was sold for $84,100 more than its original $900 purchase price) taking a swing at Scull after the auction and shouting, “I’ve been working my ass off for you to make a profit!” Or it may have been the picket line of furious taxi drivers on Madison Avenue protesting the event, handing out flyers that promised “the unveiling of Robert C. Scull.” Whatever the case, even early observers like Rose saw that the $2.2 million Robert and Ethel Scull took home that night marked a pivotal shift in the relationship between artist, collector and public.

There had been a certain mythology about the character of the art market in the 1960s, in many ways a false narrative, but one that nonetheless held sway as an ideal: Gallerists would be, on the whole, honorable lovers of art; prices would be set modestly by this small group of gallerists; the whole shebang would be run on behalf of the art community, a group that would include the artists themselves, the gallerists and their clients—like-minded art collectors. But the 1973 Scull auction exploded these gentle conceits, replacing them with what some have deemed the “superstar” narrative for contemporary art. As described by one art historian, this new narrative “centered around a notion of price.” Superstar prices, he writes, “are set high and increased frequently and sharply.” The high-risk, short-term profit-taking and aggressive marketing that accompanied the Scull auction—so anomalous then, so typical now—comprised a rough draft for the “pricing script” that has come to hold global sway. And nothing says glamour and success quite like excess.

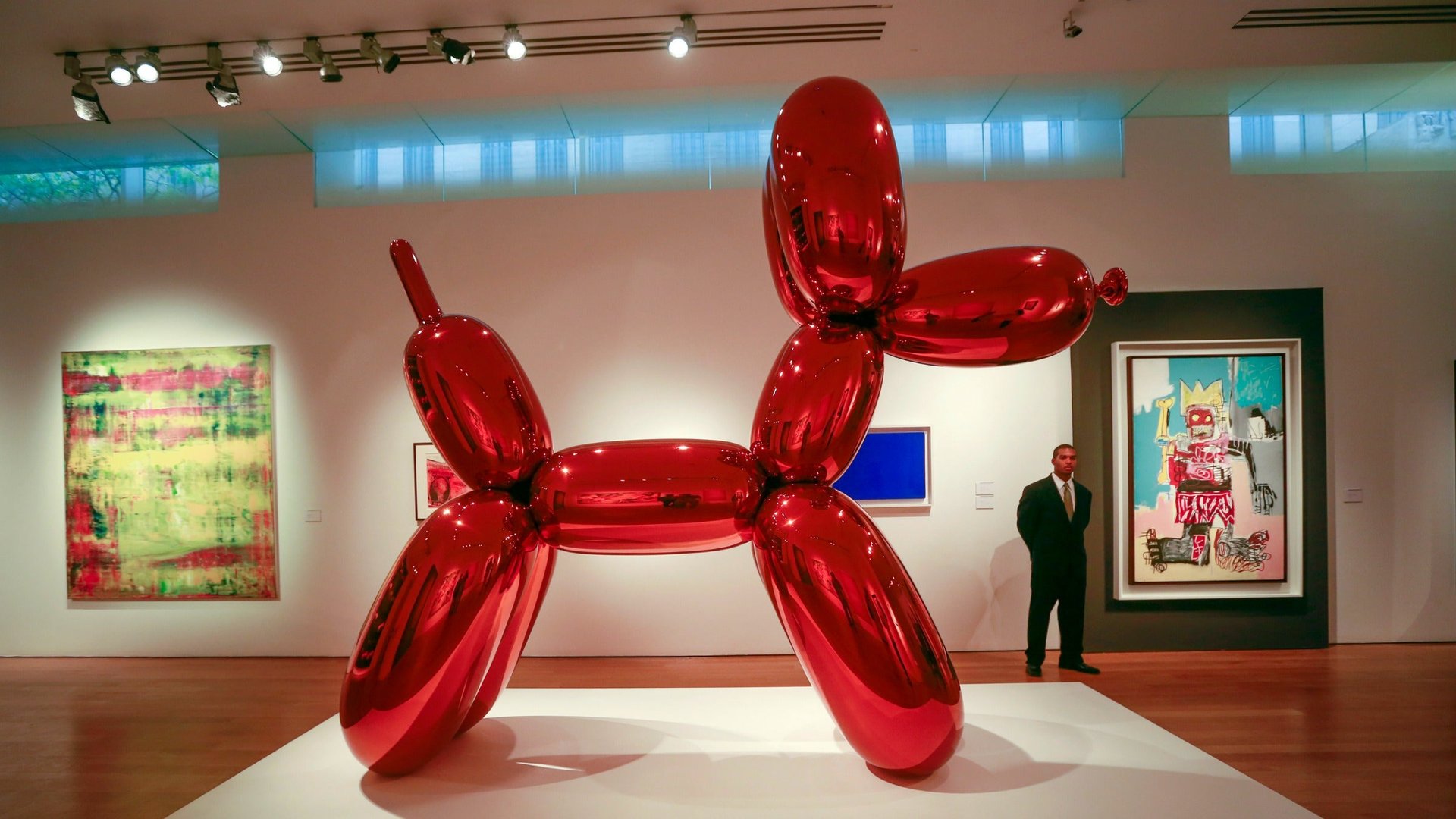

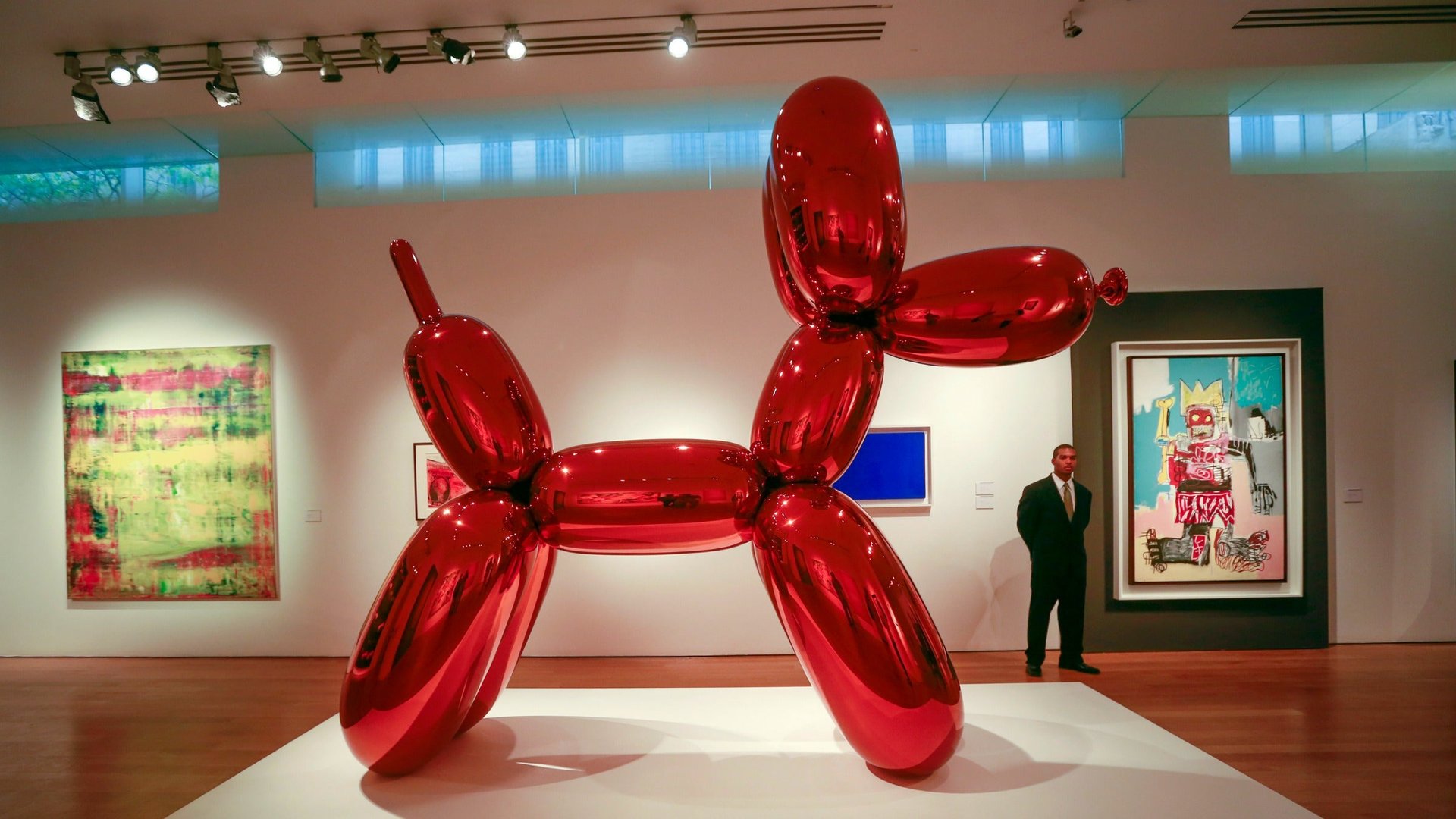

What strikes me, reading this week’s headlines on Tuesday’s “record-breaking” $691.5 million Christie’s auction and the $142.2 million purchase of the Francis Bacon triptych by dealer Bill Acquavella on behalf of an unnamed client—that is, when I can tear myself away from the coverage of ongoing relief efforts in the parts of the Philippines devastated by Typhoon Haiyan, where the bodies are piling up and residents are being encouraged to flee for their lives—what really strikes me is the way that what was in 1973 considered such an aberrant outrage is now just standard common sense, if not common cents. “Bacon Triptych Fetches $142 Million, A Record Price” (NYT), “Bacon, Koons Set Major Records in New York” (Bloomberg), “Francis Bacon work tops Edvard Munch’s ‘The Scream’ for auction record” (LA Times) and simply: “The Most Expensive Art Ever Sold At Auction: Christie’s Record-Breaking Sale” (Forbes.com). As far as I know Jeff Koons did not attempt to punch the billionaire industrialist who sold the artist’s “Balloon Dog (Orange)” for $58.4 million, no pickets were reported outside the event, indeed no one seems to have batted an eye. The Washington Post’s Katherine Boyle cynically wonders why anyone is even surprised by these sale prices anymore.

But there was another bit of news related to auctions of contemporary art this week, and like the Christie’s sale it has a back story that goes back to that transitional moment in the early 1970s. To be sure, the headlines were rather less eye-catching: “Dia’s Auction of Artworks Is to Proceed” is how the New York Times put it. The Dia Art Foundation’s co-founders Heiner Friedrich and Fariha (née Philippa) de Menil withdrew a lawsuit against the Dia foundation that was seeking to block the sale of works from its collection at a Sotheby’s auction on Wednesday evening. Major works by an impressive list of artists took in well above what was estimated—Cy Twombly’s 1959 drawing “Poems to the Sea” alone sold for a stunning $19.2 million, some $11 million over its high estimate —with that money to be used by Dia to finance a major acquisition of artworks at a time when much of the foundation’s money is tied up with a campaign to build a new museum for itself in Chelsea. When I interviewed oil-heiress-turned-Sufi-leader Fariha de Menil about Dia’s early days for a Bidoun magazine profile in 2010, it was clear that Dia, which was originally (and somewhat secretively) established in 1974, was intended as a kind of refuge for artists and artworks from the high-octane market starting to take shape in the wake of the Scull auction.

What resulted was a remarkably prodigal and productive decade of grants, commissions and initiatives: there were single artist museums, massive earth works, wild experiments and permanent installations by single-minded artists including Donald Judd and Walter De Maria. Profit-taking and strategic investment were the furthest things from their minds; and so it would have remained in a perfect world. But, as I write in my piece, Dia’s founders’ vision was extraordinarily expensive — and its finances fragile: by eschewing the secondary market as a source for revenue, the early Dia foundation was left almost completely dependent on the share prices of a single oil services company. In the early 1980s, it all came apart: “Amid falling share prices and rumors of an investigation of financial improprieties by New York’s attorney general, a group of concerned de Menils had launched a coup in 1984, replacing the original board with a respectable firewall of uptown lawyers and suits, putting much of Dia’s real estate and art holdings on the auction block and sequestering Philippa’s money in a trust…” Dia’s impractical founders were on the outs, as was their idealistic—perhaps impossible—vision of the foundation as creating a new model of art patronage, supporting artists by completely freeing them from market pressures, allowing them to create artworks of lasting trans-historical, public—and unsaleable—value.

It’s hard not to read today’s auction headlines without a sense that these two sales together reaffirm the triumph of Scull’s profitable vision and the successful derailing of de Menil and Friedrich’s utopian alternative. As Marianne Stockebrand, the one-time director of Donald Judd’s Chinati Foundation, puts it to the New York Times: “Dia was like a partnership with these artists, and there was a great amount of trust on the artists’ part, an almost family-like sense… What does the foundation expect now in terms of respectability and trust from artists in the future? I don’t think they realize this will have long-term consequences.”

The final, bitter twist to this twofold tale? New York audiences got to see many of the works from the 1973 Scull auction at a 2010 exhibition titled “Robert and Ethel Scull: Portrait of a Collection.” The venue? Bill Acquavella’s Acquavella Gallery.