An artist used the hair of sex workers to critique what it means to be a “good girl”

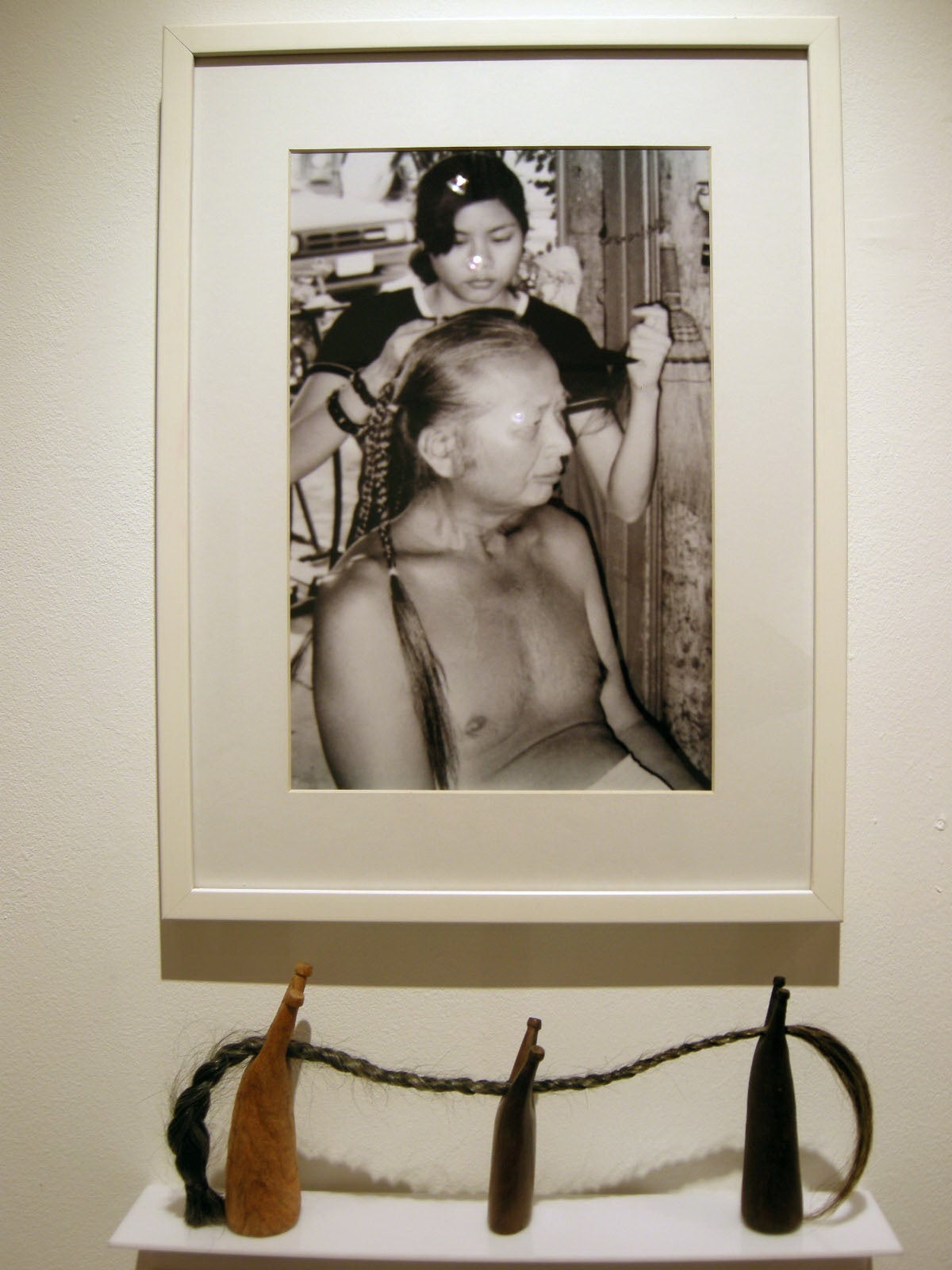

Imhathai Suwatthanasilp has a long and intimate relationship with hair. It began when her photographer father asked her to cut his hair in 2003 after he was diagnosed with liver cancer.

Imhathai Suwatthanasilp has a long and intimate relationship with hair. It began when her photographer father asked her to cut his hair in 2003 after he was diagnosed with liver cancer.

“Our father divided the hair into four pigtails, each 47cm long, for each of the four sisters. The hair, as part of his body, represents love, blood and flesh, and it was for us to keep when he could no longer be with us,” recalled the Thai artist.

Suwatthanasilp’s father died in 2008, but hair still shapes her work. After cutting her father’s mane, the then arts student at Bangkok’s Silpakorn University began collecting her own hair and making art with it, creating a deeply personal brand of artistic language with the delicate weaving and crocheting of hair in her works, which often reflect complicated feelings towards life, familial connections, and femininity.

For Good Girls Go to Heaven, Bad Girls Go Everywhere, an installation that is on show at the inaugural Bangkok Art Biennale, which opened Oct. 19 and runs until Feb. 3, Suwatthanasilp turned to other people’s hair for inspiration, weaving hair from sex workers in Thailand onto the 174 parts of a vintage sewing machine. She said the hair crochets resemble the shapes of flowers, leaves and grass, as if new life was born out of cold machine parts. Through the work, Suwatthanasilip said she wanted to address the prevalence of prostitution in Thailand, and critique how sex workers are judged by society.

“By changing the shape of the lifeless sewing machine parts into new and lifelike objects… I want to tell people that life is able to grow out of something cold, just like how sex workers survive the judgement of the society and social structure,” she told Quartz.

Many families in Thailand depend on the earnings of family members in the sex trade, and it is estimated that the country of 70 million now has anywhere from 800,000 to 2 million sex workers, according to the Nation. While the numbers and visibility of sex workers suggest relative acceptance in comparison with other countries in the region, the law treats them as blameworthy. It’s illegal to offer sex or work in an establishment that sells sex under a 1996 Thai law—the former is punishable with a fine and the latter with a fine and/or a month in prison—but not for customers to buy it.

Recently, the country has seen discussions on whether to abolish the ban on prostitution and regulate the business. That would shift the law to being protective, rather than punitive, of these workers, a stance that Suwatthanasilp is in favor of.

“The more we try to cover it up, the worse it gets,” said Suwatthanasilp. ”Sex workers want their work to become legal, and to be given worker’s ID so that they can be identified and their rights can be protected.”

As part of her research for the piece, Suwatthanasilp reached out to the Empower Foundation in Chiang Mai, an organization aimed to support women in the sex business by equipping them with additional skills while also advocating for decriminalizing and offering them work protections.

“For example, people thought these women can begin a new life by learning to sew with a sewing machine,” she said, referring to the donation of sewing machines made to the foundation. “While people were trying to help, they were also looking down on the women. Prostitution was seen as a ‘bad’ career and people tried to force them to take a new, so-called ‘good’ career.”

But Suwatthanasilp found out that these sewing machines were never used as expected. She also says that many sex workers she interviewed chose this way to support their families because they came from very poor families and lacked education.

“One of the women I knew worked in the business her whole life just to send her children to university,” she said. “But these sewing machines simply represent society’s judgement on the value of human beings and criticisms against sex workers.”

Suwatthanasilp hopes her artwork will inspire people to rethink their judgments of these women.

“They are just normal people who want to help their families,” said Suwatthanasilp. “[How] are they ‘bad girls’? They should be respected.”