The Crispr baby news was carefully orchestrated PR—until it all went wrong

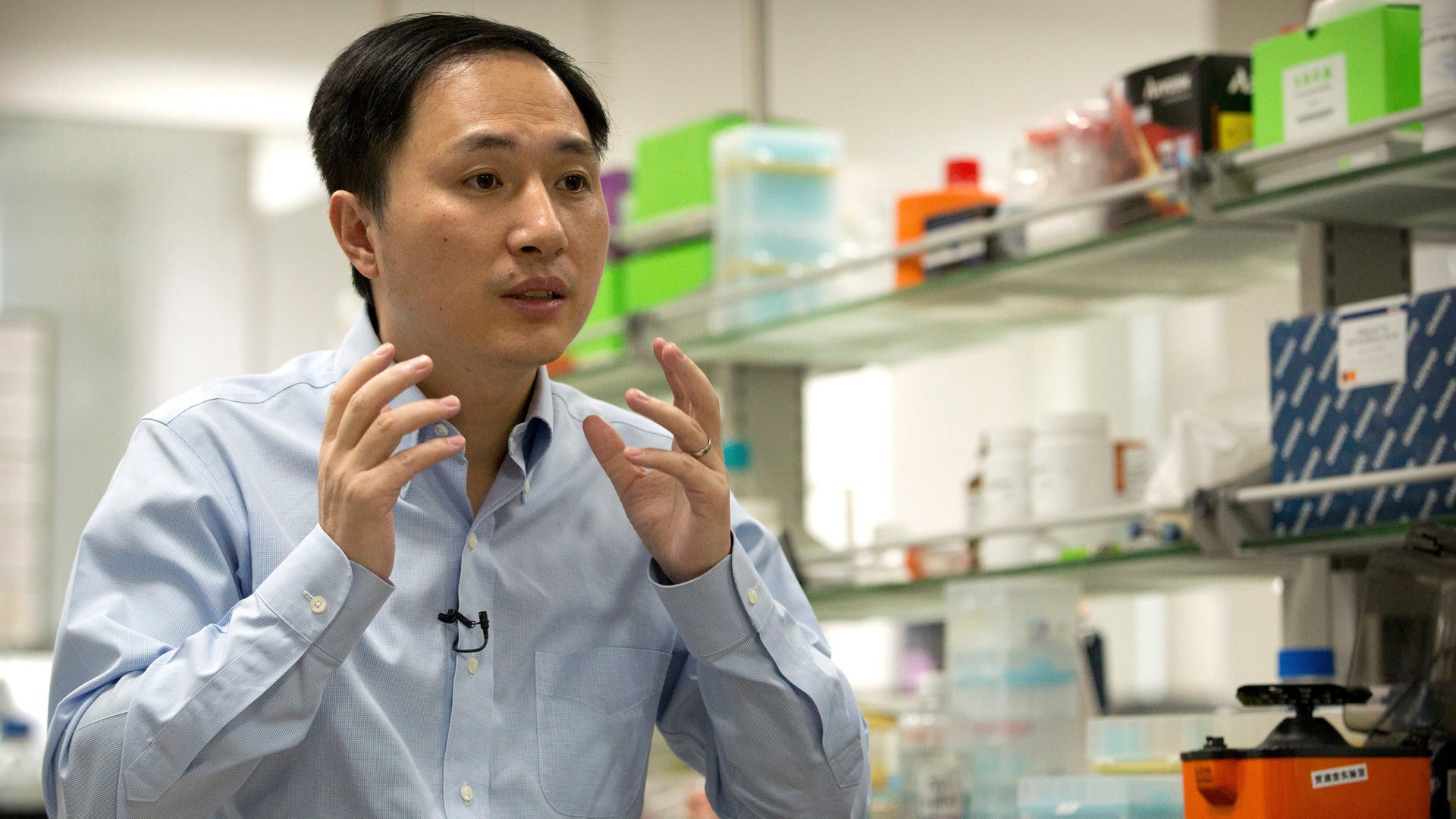

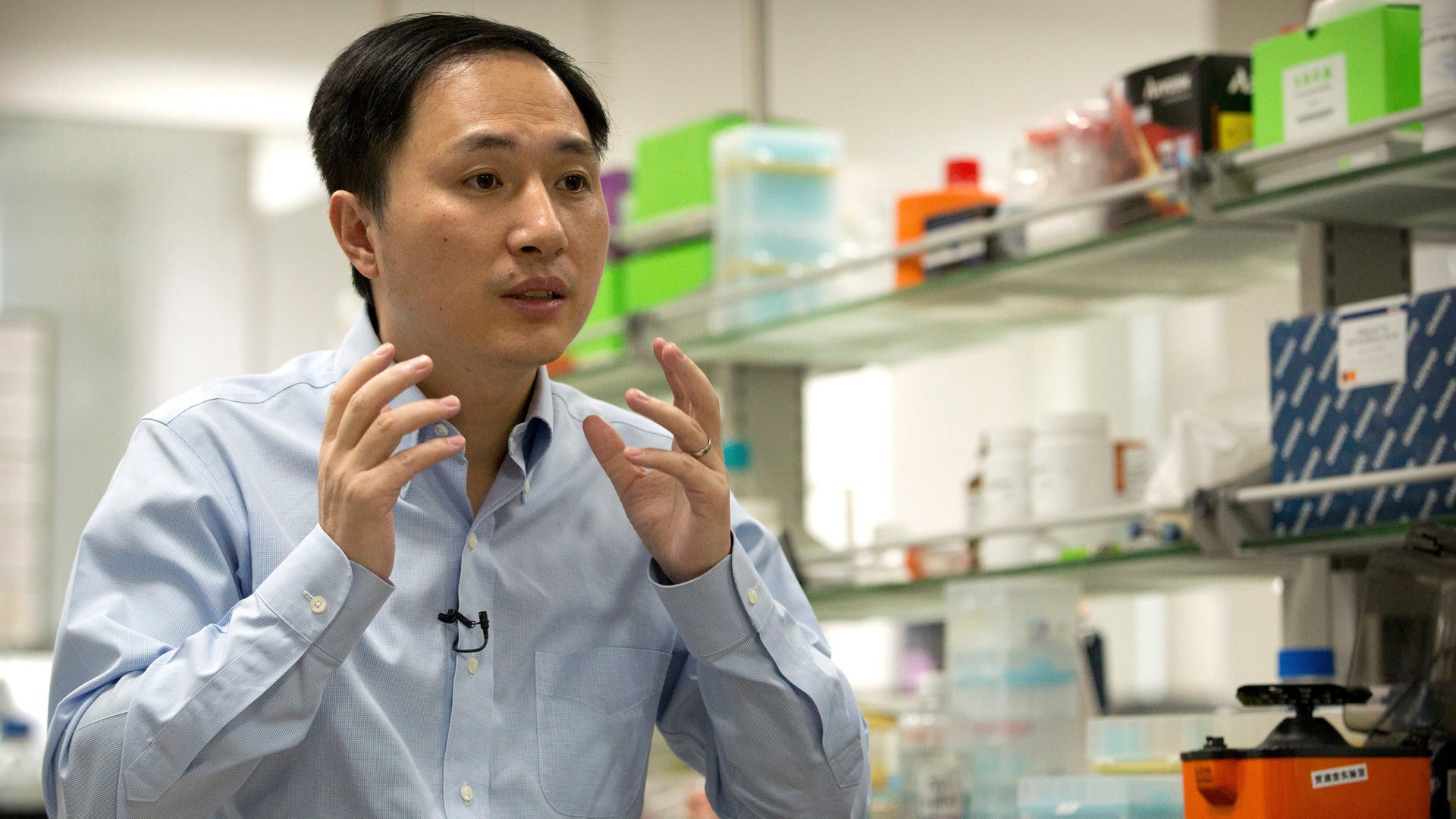

He Jiankui didn’t wake up on Sunday expecting his world to change. He’d authored a paper that was to be published on Monday, and planned to speak about his work at the most important conference in his field of study on Wednesday. And he’d spoken with a reporter from the Associated Press (AP), so he was likely aware that sometime before his speaking engagement, the AP might publish a blockbuster report about his great scientific achievement. He knew international attention was coming for him, and he had a plan.

He Jiankui didn’t wake up on Sunday expecting his world to change. He’d authored a paper that was to be published on Monday, and planned to speak about his work at the most important conference in his field of study on Wednesday. And he’d spoken with a reporter from the Associated Press (AP), so he was likely aware that sometime before his speaking engagement, the AP might publish a blockbuster report about his great scientific achievement. He knew international attention was coming for him, and he had a plan.

Then Antonio Regalado, biomedicine editor at MIT Technology Review, ruined it. On a recent trip to China, Regalado heard rumors that He’s lab at the Southern University of Science and Technology in Shenzhen was undertaking research on gene-editing human fetuses. A simple Google search using the terms “He Jiankui” and “CCR5” (the gene being edited) led him to clinical-trial registration documents that revealed He had recruited couples for a clinical trial to create the world’s first gene-edited baby.

Regalado called He on Sunday morning (Nov. 25) to ask whether the trial had led to the birth of any gene-edited babies. But He declined to comment. So Regalado published his story, which raised a number of issues about the risks of using gene-editing technology on human embryos and quoted many scientists who opposed the idea. An inaugural international summit on gene editing in 2015 concluded that, while research could benefit from using the technology on human embryos, gene-edited embryos should not be used to establish a pregnancy. The risks to the child born were still too high, because gene-editing tools weren’t accurate enough yet. Now, on the cusp of the second international summit, He seemed to have flouted the international consensus.

Hours after Regalado published his story, Marilynn Marchione of the AP published her reporting on He’s work. Marchione, unlike Regalado, had received early access to He’s work, and her reporting confirmed that He had helped make the world’s first gene-edited babies: twin girls born weeks earlier, with their CCR5 gene edited in a way that, He said, would make them resistant to HIV infection. Marchione, like Regalado, spoke to scientists who considered He’s experiment unethical. She raised worries that people with mutated CCR5 genes had higher risk for infections from other viruses, such as West Nile.

He may not have expected the media attention to come so soon, but he was prepared for it: soon after the AP article went out, He published five videos on YouTube, where he announced that the twin girls, Lulu and Nana, were “as healthy as any other babies.” In one video, he set out what he thinks should be five ethical principles for reproductive technologies, including gene editing. In another, he anticipated a backlash: “I believe families need this technology, and I’m willing to take the criticism for them [using it],” he said. Throughout the videos he used the term “gene surgery” instead of “gene editing” to describe the technology. (“Surgery” is a better term, He wrote in an article published on Monday (Nov. 26) in the Crispr Journal, because the use of other terms invokes “disgust” among the lay audience.)

All this happened in a few hours, and it was one of the most highly produced medical-science announcements I’ve seen in six years of reporting on the subject. I’ve come to expect organizations like NASA to have such high-value production for their multi-million or multi-billion dollar space programs, but not a small lab in a little-known university.

Although the rollout was likely pushed ahead of schedule because of Regalado’s article, He was prepared to use media attention to promote his message on his own terms. And, to some extent He succeeded: The news of his claims made headlines around the world and, as of publishing this article, He’s YouTube videos had been viewed nearly 200,000 times.

Nevertheless, the backlash was immediate. Almost universally, scientists were opposed to He’s experiments. He’s videos suggest he expected and accepts some amount of criticism, but it doesn’t seem like he prepared for the level of scrutiny that follows this sort of publicity. (He didn’t reply to request for a comment.)

The South China Morning Post, for example, reached out to the National Health Commission (China’s top health body), He’s own university, the hospital where the girls were allegedly born, and the members of the ethics committee that approved the clinical trial. No one seemed to know that the experiments were happening or whether He had received the necessary approvals to conduct them. It’s not clear what his funding sources are.

Within 24 hours of the news breaking, the Shenzhen City Medical Ethics Expert Board said it would begin an investigation, because “according to our findings [He] never conducted the appropriate reporting according to requirements” and the Chinese Academy of Sciences would launch its own investigation. The president of He’s university reportedly called for an emergency meeting of all the researchers involved with the project.

As the doubts began to pile up, the question moved away from whether what He had done was ethical to whether his claims were real at all. Could He have pulled off a hoax?

“Normally there will be a scientific paper. But instead there is… just a press release. We’re all talking about these babies. Have you seen a picture yet?” asked Regalado. “Is it a fraud? The question is out there. We still didn’t know.”

Some on Twitter suggested this might be similar to the 2003 announcement made by the chief executive of Clonaid, a US-based human-cloning organization, that a human baby clone named Eve had been born. Clonaid never published pictures of Eve, but the press gave the company the benefit of the doubt.

“Journalists were looking for the cloned baby. People believed it might happen at any moment,” says Regalado. “[Clonaid] took advantage of people’s expectations. They put out this fake press release. They got a lot of attention and media coverage.”

Though there are parallels—He has notably not shared pictures of Lulu and Nana—Regalado says He’s claims are unlikely to be fraudulent. “The argument against it being fake is that it’s doable,” Regalado says. “The reason we are worried about the Crispr baby is that it’s technically easy to do.”

He’s career is now at risk. “The penalty to [He] as an academic, scientist, and entrepreneur in bioscience of doing something that’s made up is very high,” says Regalado. If He has committed fraud, he could be outcast from the scientific community just like Hwang Woo-suk, the Korean scientist who was widely considered an innovator in his field of stem-cell research until other scientists exposed him for fabricating experiments in the mid-2000s. Hwang was subsequently fired from the Seoul National University and served prison time for embezzlement and bioethical violations.

Even if He’s study is legitimate, it would still anger many scientists, who argue that He has put the gene-editing community at risk. He’s cavalier behavior could provide fuel for the arguments of critics of the research field (and even some supporters) who have called for a moratorium on gene-editing of human embryos.

He is expected to speak at the second International Summit on Human Genome Editing in Hong Kong tomorrow (Nov. 28). Maybe the world will learn answers to some of the many questions He’s work has raised, or maybe He won’t show up.

Update: He did speak at the meeting in Hong Kong but mostly gave evasive answers. The most salient piece of new information was that another Crispr baby may be on the way.