What the financial media don’t want you to know: the myth of the merger scoop

The “merger scoop” has been a staple of financial journalism for decades. Careers, and even entire business models, have been built around being the first to report that Company Y is buying Company Z. But there is an alternate view that deals scoops are far from the pieces of hard-hitting, journalistic brilliance they are often portrayed to be: In fact they are almost always the result of strategically calibrated leaks in the endgame of a given deal.

The “merger scoop” has been a staple of financial journalism for decades. Careers, and even entire business models, have been built around being the first to report that Company Y is buying Company Z. But there is an alternate view that deals scoops are far from the pieces of hard-hitting, journalistic brilliance they are often portrayed to be: In fact they are almost always the result of strategically calibrated leaks in the endgame of a given deal.

A new study from City University London’s Cass Business School, Mergermarket and transactional software company Intralinks argues that most M&A news is leaked intentionally, rather than uncovered through ingenuity or released by accident. Intralinks has a horse in this race: The company sells “virtual data rooms” which are designed to enable secure sharing of confidential information between buyers and sellers during a sale process. Yet the research still paints an interesting picture.

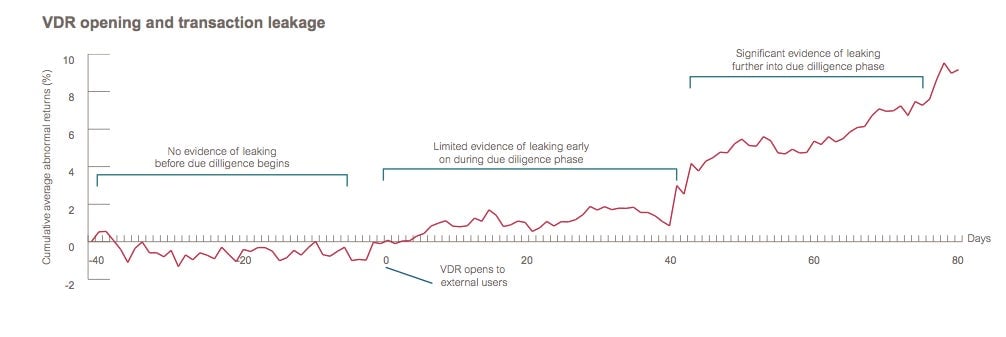

In 142 transactions involving a publicly-listed merger target between 2008 and 2012, there was no evidence of leaks, as measured by abnormal share price movements, before the start of the due diligence process (when a potential buyer is given the chance to look at at an acquisition target’s books). There’s plenty of potential for a leak at this stage of the proceedings: Companies are talking to each other, emails can be misdirected, documents lost. But leaks simply don’t happen, according to the study, because it’s in nobody’s interest for information that could potentially scupper the deal to get out at this stage.

After due diligence begins, there’s still only limited evidence of leaking—until we get past the 40-day mark. Then leaks start to proliferate. The report puts this down to the fact that when due diligence is dragging on, it usually means negotiations have hit a roadblock. A well-timed leak to the media can help one side of the deal gain the upper hand—making it look like competition for an asset is heating up when it isn’t, for example. ”Leaks look increasingly likely to be motivated by one party being unhappy with how negotiations are progressing and therefore choosing to leak information to push the deal in a direction they prefer,” the report says.

This dynamic may well have been at work in the recent aborted sale of BlackBerry. As the auction process veered off course and the company’s deadline for finding a buyer approached, some fairly unconvincing reports emerged linking the company first to Lenovo, and then to Facebook.

Reuters’ blogger Felix Salmon has previously made a strong case for the demise of the M&A scoop. But for traders in particular, getting news of a deal just a few minutes or even seconds earlier than a competitor can justify the subscription to a news outlet many times over. What’s more, it doesn’t even matter if the news of the deal is true. As long as it moves markets, whoever gets it first has the edge. That’s why the financial media makes treats merger news with such reverence—even if the “scoops” matter little to the public at large.