New reforms might kick-start China’s private sector. Or not

Out of every “third plenum”—that key Communist Party meeting when a new administration sets its economic agenda—the Party usually published two documents: a “communique” that broadcasts the leadership’s administrative philosophy and the “decision” charting how it will be enacted. While the communique put out on Tuesday (Nov. 12) astonished China-watchers with its vagueness, the 60-point “decision” released earlier today explains reforms more concretely. Some hail it as the “boldest reform in decades.”

Out of every “third plenum”—that key Communist Party meeting when a new administration sets its economic agenda—the Party usually published two documents: a “communique” that broadcasts the leadership’s administrative philosophy and the “decision” charting how it will be enacted. While the communique put out on Tuesday (Nov. 12) astonished China-watchers with its vagueness, the 60-point “decision” released earlier today explains reforms more concretely. Some hail it as the “boldest reform in decades.”

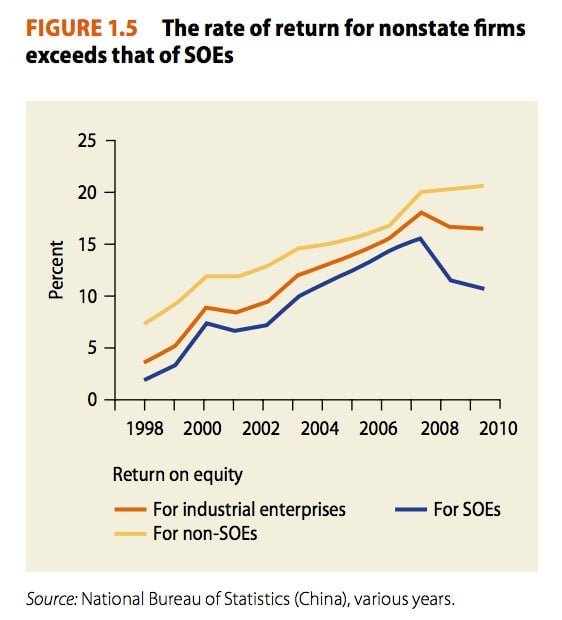

Two of the boldest such reforms are designed to revive China’s sickly private sector and boost consumption. One is an increase in the dividend state-owned enterprises (SOEs) must pay the government; the other is a plan to let private capital set up small banks. Both are good news: The government has up to now relied on controlling economic growth via the SOEs, starving non-state companies. But a closer look at both reforms suggests it’s too early to get that excited.

First, the SOE reform. In the past, SOEs paid the government a dividend on their net profits of up to 15%. The “decision” released today ups that to 30%, to be “used to improve people’s livelihood.” China-watchers have long seen such a form as a good way to redistribute state wealth—but only if goes hand in hand with reforms of how the state gives out money and resources.

Moreover, Patrick Chovanec of Silvercrest Asset Management explains, though the reform is meant to give an advantage to private enterprises that don’t pay the dividend, it could paradoxically end up hurting them. The government becomes “more dependent on SOEs as a source of finance for what they want to do and therefore those monopoly profits are that much more important to protect,” Chovanec tells Quartz. “You can have a shift from investment to consumption…. But it’s still the government making that decision and it gives the government in some ways an even bigger role in Chinese economy.”

The other big reform—allowing private capital to set up small banks—is important because, in theory, it will channel funds more efficiently than China’s big state-owned banks do. The loans from these small banks will go to small non-state companies, which have been starved of capital for the last five years.

But two years ago, the government rolled out a pilot of this plan in Wenzhou, a city in Zhejiang province, to little effect. Chovanec is skeptical that a nationwide plan will be effective until the government winds down its excessive lending habit. ”Before you can talk meaningfully about the role private capital will play in the banking system, you need to have real accountability in the banking system,” he says. “You need to remove the distortions that are warping the Chinese economy and pushing it toward an unstable state.”

That’s not to say these reforms aren’t important. With broader changes to the state’s grip on the economy, and more discipline on lending, they could revitalize China’s private sector and help the economy grow far more sustainably than it has in the last few decades.