Monarch butterfly populations in the west are down an order of magnitude from last year

There’s not much to be grateful for after the great Western Monarch Thanksgiving Count this year. The three-week volunteer effort in California dispatches scores of volunteers to hunt in their woods, backyards, and fields in search for the colorful migrating butterfly.

There’s not much to be grateful for after the great Western Monarch Thanksgiving Count this year. The three-week volunteer effort in California dispatches scores of volunteers to hunt in their woods, backyards, and fields in search for the colorful migrating butterfly.

This year, signs of trouble came early.

Far fewer of the insects were heading south this year, and those that have arrived did so a month late, according to Xerces, a non-profit conservation group for invertebrates. One researcher said it was the fewest monarch butterflies in central California in 46 years. Surveyors at 97 sites found only 20,456 monarchs compared to 148,000 at the same sites last year, an 86% decline. It’s possible more insects will make the journey late this year, says Xerces, but that now seems unlikely.

The minimum population size before the species experiences “migration collapse” is unknown, but a 2017 modeling paper in Biological Conservation (pdf) found that 30,000 butterflies adult butterflies are probably the smallest viable population. Without this critical mass, there aren’t enough insects in the western monarch population to continue one of the world’s most remarkable lifecycles.

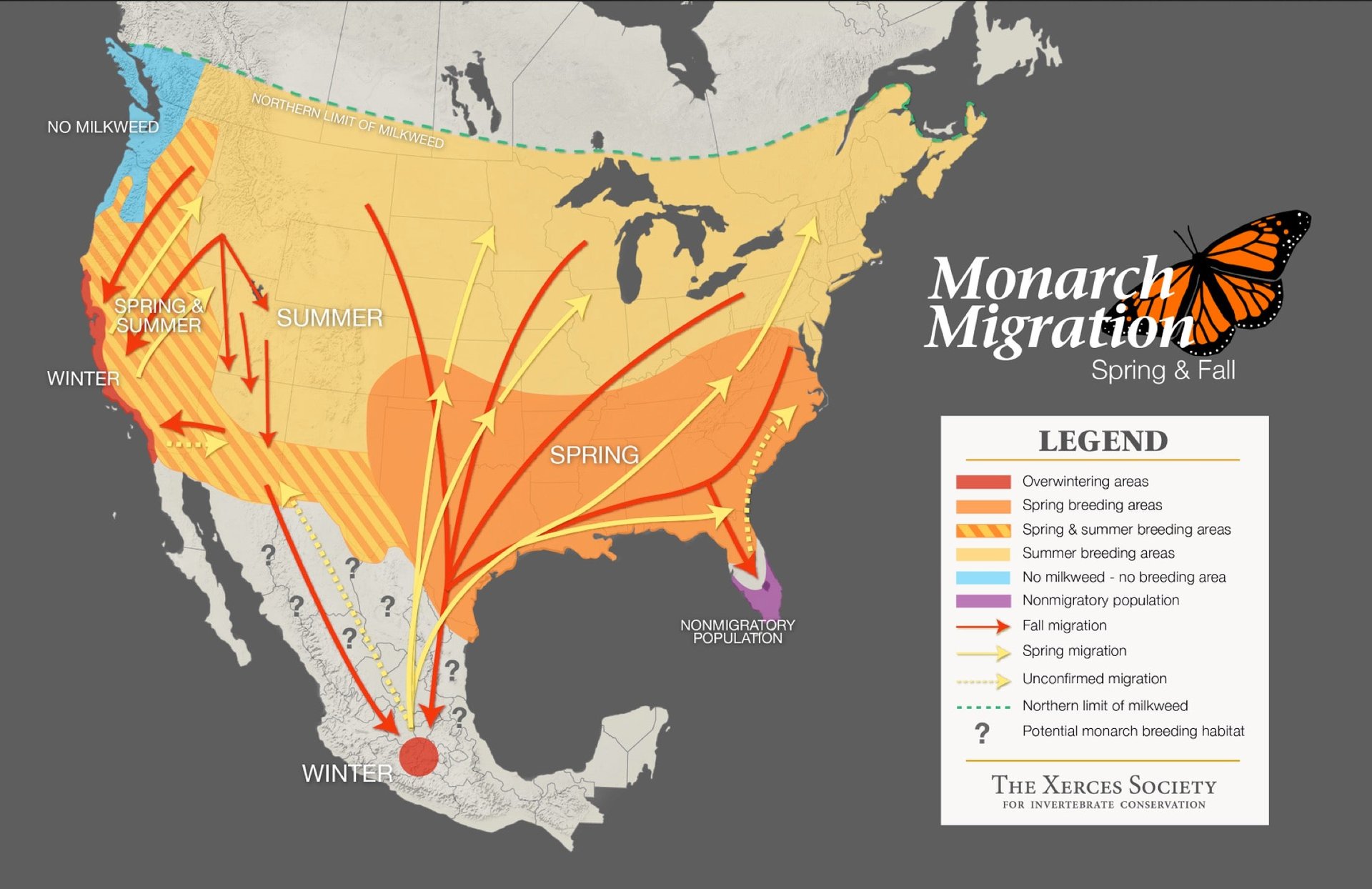

Each year, monarchs perform an epic migration. Starting from the fields of Canada and the northern US, the insects fly thousands of miles to the oyamel fir forests of Mexico where they overwinter from October to late March. Afterwards, they reverse the journey, passing through life stages from egg to larva (caterpillar), pupa (chrysalis), and adult. Along the way, monarchs feed on at least 44 species of plants, milkweed most prominently, passing through desert landscapes, as well as lush grasslands and farms. Yet no single insect completes the journey. Rather, it takes three or four generations, each one traveling part of the way, to reach their final destination.

Monarch populations are now in marked decline. While monarch populations east of the Rocky Mountains fared better this year (only down by 14.8%), the Western population is in free fall. Its population has fallen by 97% since the 1980s, and more than 99% from its original abundance. Overall, the number of butterflies returning to the winter grounds in Mexico keeps declining.

The biggest reasons are habitat loss and pesticides across the butterflies’ breeding and migratory range. This year’s steep drop is probably due to extreme weather, at least partly resulting from climate change. Late rainstorms in March, as well as an intense, extended wildfire season across California, have battered the species. The state’s forests have yet to recover from the record-breaking drought stretching from 2011 to 2017.

It’s not just monarchs: “The insect apocalypse is here,” reports The New York Times. Sites around the world are seeing species population declines of 80% or more. These losses mean populations can effectively collapse leading to “functional extinction,” the point at which depopulated species no longer meaningfully support their ecosystems, reducing their resilience, and undermining other species.

Scientists are still figuring out how to respond. What can you do? Monarchs need special habitat. You can plant native milkweed, eliminate pesticides and garden with flowering species supplying nectar. Xerces suggests joining citizen science efforts such as the Western Monarch Thanksgiving Count, the Western Monarch Milkweed Mapper, and a New Year’s count. All these help researchers identify and protect winter migratory sites (despite being one of the world’s most famous insects, scientists are still learning about the species’ migratory pathways, roost trees, and nectar resources). Finally, there’s a Mayor’s Pledge for cities to make themselves into stopovers for the beleaguered butterfly.

Correction: A previous version of this post stated the incorrect name of The Xerces Society.