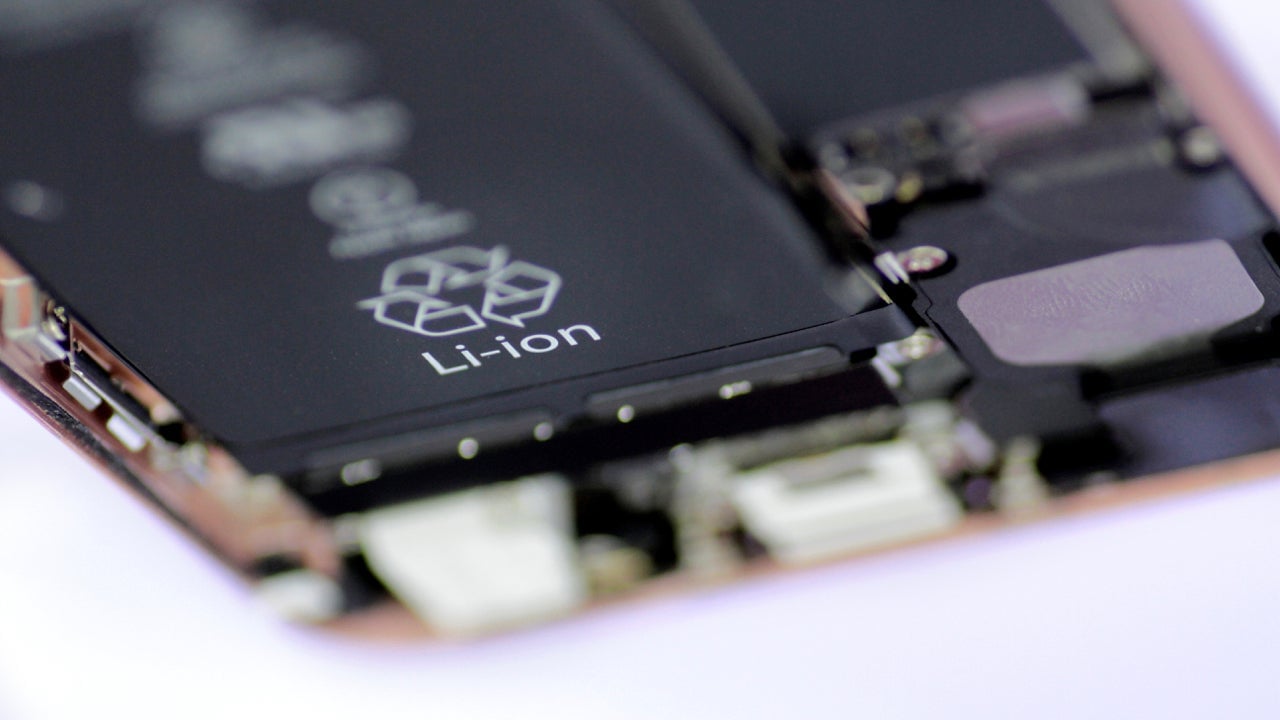

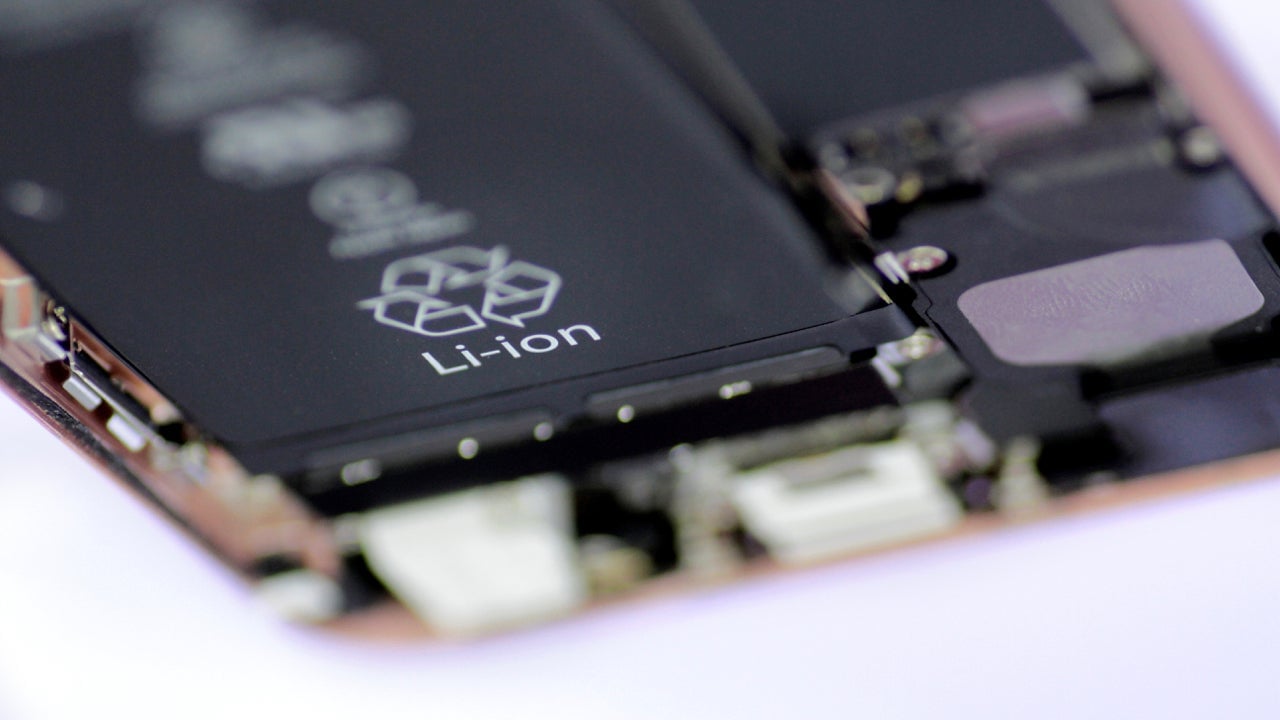

What really powers your smartphone and electric car

The rechargeable lithium-ion battery helps define our era. It powers our smartphones and electric cars, and promises a future where we’re better able to store renewable energy. It also requires lithium and cobalt, minerals that some of the world’s poorest countries happen to have in abundance. That should be good news for all concerned, but mismanagement and graft—common in extractive industries—are making the latest mining boom look uncomfortably like the bad old days of previous booms.

The rechargeable lithium-ion battery helps define our era. It powers our smartphones and electric cars, and promises a future where we’re better able to store renewable energy. It also requires lithium and cobalt, minerals that some of the world’s poorest countries happen to have in abundance. That should be good news for all concerned, but mismanagement and graft—common in extractive industries—are making the latest mining boom look uncomfortably like the bad old days of previous booms.

This week provided reminders of that. First, the Democratic Republic of Congo tripled its levies on cobalt, of which it has the world’s largest natural supply, in a move that could result in pricier smartphones and production slowdowns for electric-car makers. Also, HSBC released a report showing that the projected market share of electric vehicles will be smaller than first thought, due to the high price of lithium and cobalt amid soaring demand.

Dominance of cobalt supply has proven a cash-cow for the DR Congo’s government, but that hasn’t helped ordinary citizens much, with just a sliver of mining exports funding the national budget. The DR Congo is among the poorest countries in the world, despite its vast mineral wealth. Gécamines, the state-owned mining company, has long faced allegations of corruption. It recently denied such allegations while conceding that (link in French) “the economic benefits of mining in the DRC do not contribute as much as they should to the wealth of our country.”

The government’s move this week wasn’t entirely unexpected. Last year, the country classified cobalt as a “strategic metal” and threatened to push mining tariffs up. For decades, colonial powers exploited the area for its mineral wealth. The country’s current leaders want to cash in, too, even if it’s at the expense of their own people.

To secure their supply of cobalt, smartphone makers Apple and Samsung—and electric-vehicle manufacturers BMW and Volkswagen—have entered into direct talks with miners in the DR Congo. That, however, has not removed the Congolese government, which has proven to be a hard middleman to please. Miners have looked to Canada and Namibia as alternatives, but with more than half of the world’s cobalt beneath the ground, the DR Congo’s ruling regime has an upper hand.

The lithium triangle

In South America, the Andean region’s “lithium triangle”—including parts of Chile, Argentina, and Bolivia rich in the mineral—is witnessing similar power plays (paywall). Until now, Chile has easily outpaced Argentina and Bolivia thanks in part to low production costs. Years before the DR Congo used the phrase, Chile declared lithium a “strategic” material in response to lithium’s role in the rush to develop nuclear power in the 1970s. The upshot? Today only two companies have the rights to extract lithium in Chile, limiting output.

Now that lithium is a strategic material for an entirely different rush, Argentina is positioning itself as an alternative source while Chile struggles to reform. Lithium-related investments in Argentina have increased dramatically in recent years. President Mauricio Macri is creating a “Goldilocks” regulatory environment that will make Argentina “just right,” Bloomberg reported this week (paywall), though next year’s general elections could dishevel this house.

In Bolivia, president Evo Morales’ state-centric regime has scared many investors away from the lithium-rich area that once filled Spain’s coffers with silver. But with the world’s second-largest lithium deposits, Bolivia aims to become Tesla’s main supplier, though, in a contradiction, to do so through state-run mining operations that lack sufficient expertise (paywall).

China, for its part, already controls most of the world’s cobalt supply (paywall), with Chinese firms being more than willing to do business with the DR Congo despite ethical issues that give many pause. It’s also gained access to Bolivia’s lithium riches, clearly hoping for a dominant position in the global battery market.

One way to avoid the geopolitics is to go beyond the earth. Asteroids are essentially floating hunks of mineral wealth, but efforts to capture it have not moved far beyond animated models. Meanwhile some deep-sea mining ventures are, despite environmental worries, hoping to uncover a viable business model by drilling into the seabed, with little success so far.

The acquisition of limited natural resources is an age-old challenge. Making the batteries of the future, it appears, is just the latest chapter.