The UN’s migration compact has the same flaw as its 1948 declaration of human rights

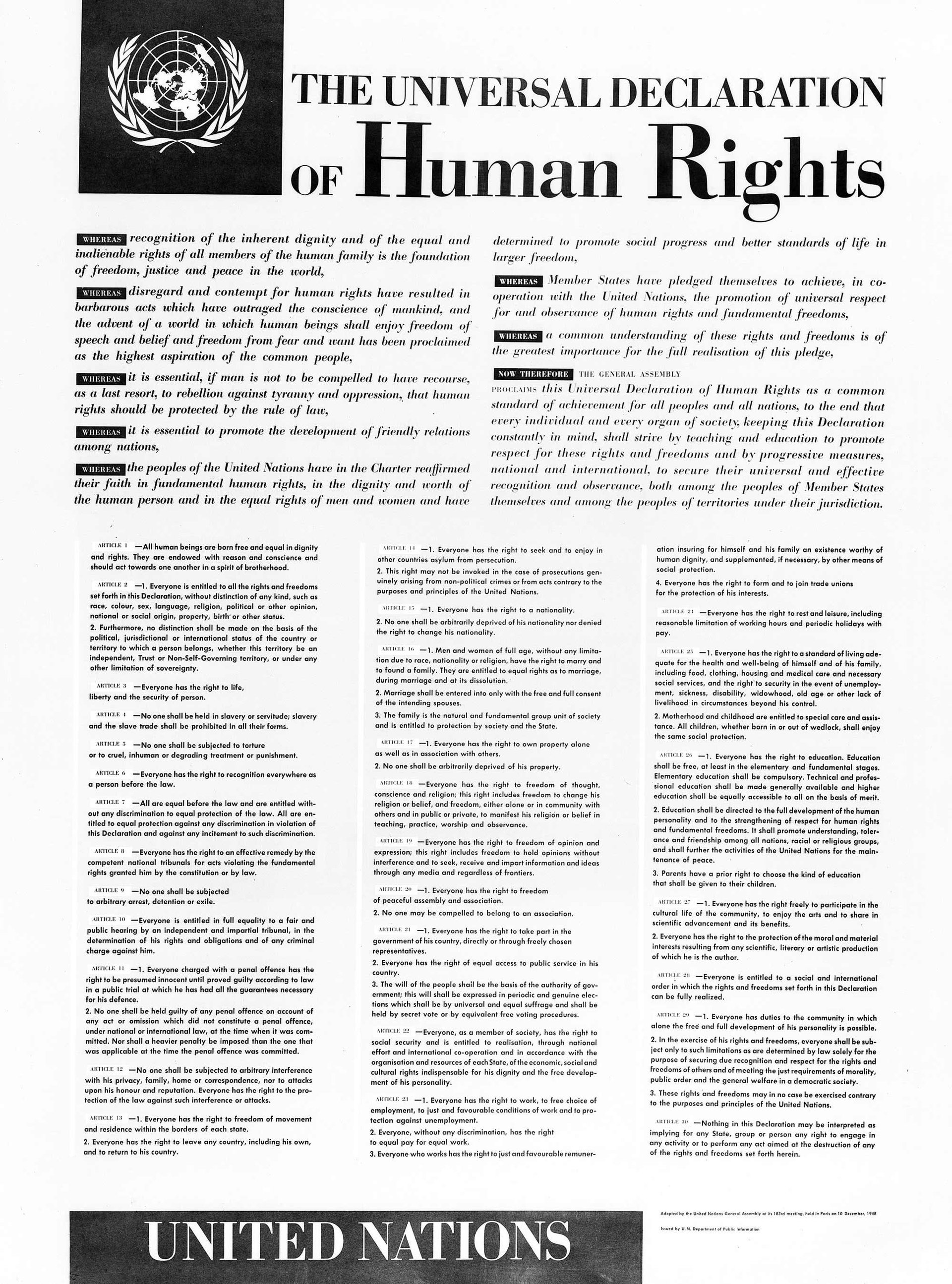

On Dec. 10, 1948, the United Nations ratified the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, a history-making agreement on what every individual deserves: life, liberty, security, equality in front of the law, freedom of movement and marriage, access to education and asylum.

On Dec. 10, 1948, the United Nations ratified the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, a history-making agreement on what every individual deserves: life, liberty, security, equality in front of the law, freedom of movement and marriage, access to education and asylum.

On Dec. 10, exactly 70 years later, UN member states met in Marrakesh, Morocco to sign the Global Compact for Migration, an agreement on what the right of free movement means today. It’s an urgent issue for poor and wealthy countries alike; there are 258 million migrants in the world and nearly 70 million refugees, and their numbers are only projected to rise, due to climate change. But today, as in the 1948 declaration, just a handful of powerful countries are quietly deciding who actually gets to enjoy that right.

Deciding for the rest of the world

The original human rights declaration was the brainchild of US first lady Eleanore Roosevelt, and championed by the United States. When it was signed in 1948, there were only 58 members states in the UN. Forty-eight of them signed.

Ten UN member-states refused to participate: South Africa, then an apartheid state, abstained from signing. So did Czechoslovakia, Poland, Saudi Arabia, the Soviet Union, the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic and Yugoslavia. Honduras and Yemen didn’t vote.

But millions of more people were not represented at all; in the African continent, for example, Egypt, Ethiopia, Liberia, and South Africa were the only countries recognized as independent UN members. For most other people in Africa, colonial powers “represented” their rights on the global stage.

Rendered invisible by that colonial structure, huge populations were denied the exercise of their human rights for years after the declaration was signed. As Kenyan activist Irũngũ Houghton reminded an audience in Nairobi’s Karura forest earlier this month, “Between the years of 1952 and 1956, the British colonial government killed one Kenyan every day for four years, […] to prevent us from enjoying the freedoms that had been enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.”

Refusing to listen

Today, another key group is absent from the negotiating table: migrants.

The compact signed in Marrakech provides guidelines on how to deal with migration, moving signatories away from ad-hoc solutions that treat migration as a passing emergency. It acknowledges the need to make legal immigration available to migrants who are fleeing issues like climate change, and not only those endangered in conflict zones. The agreement refers to “irregular migration” rather than “illegal migration,” and asks that signatory governments provide more ways for migrant to obtain legal permits. The document’s 23 goals include fighting discrimination against immigrants, and sanctioning anti-immigrant propaganda.

Participants welcomed the agreement as a groundbreaking achievement. Yet migrants themselves did not have a voice in its creation. While migrants were consulted during the drafting process, only recognized states ultimately negotiated and signed the compact. The UN’s state-based system has no way to effectively represent a demographic like migrants, which sprawls across countries. And unlike UN members, migrants don’t have official representatives who can publicly refuse to accept the agreement.

Compounding that inherent weakness, many of the countries that currently face huge influxes of migrants have deliberately spurned the compact. US president Donald Trump refused to participate in drafting the agreement, saying that it questioned national sovereignty and failed to focus on border control. Australia, Italy, Switzerland, Chile, and several other countries, also refused to sign the agreement, saying it gave undocumented immigrants too many rights. Given their central role in migrant flows, the rejection of countries like the US and Italy drains the compact of meaningful impact on global migration.

The result is that the UN emerges once again as a well-meaning body ill-equipped to deal with the actual configuration of the world. In 1948, it wasn’t able to give voice to the populations struggling for independence; in 2018, it can’t represent the populations who are forced to move in between nations, challenging the very idea of what a nation is.