The Trump administration is halting AIDS and cancer research that depends on fetal tissue

The US Department of Health and Human Resources (HHR) has halted all federal research involving fetal tissue obtained from elective abortions, according to an AIDS researcher working in collaboration with a federal facility. Fetal tissue, which provides stem cells, is a key component of medical research both within and outside government facilities and, while its use is legal, it is vehemently opposed by anti-choice activists.

The US Department of Health and Human Resources (HHR) has halted all federal research involving fetal tissue obtained from elective abortions, according to an AIDS researcher working in collaboration with a federal facility. Fetal tissue, which provides stem cells, is a key component of medical research both within and outside government facilities and, while its use is legal, it is vehemently opposed by anti-choice activists.

In September, the HHR ordered an audit of all National Institutes of Health (NIH) research involving fetal tissue, which the NIH procures through Advanced Bioscience Resources (ABR). At the same time, the FDA terminated its contract with ABR, the sole supplier of fetal tissue to federal laboratories, effectively banning its use by government agencies. The impact of the ban on medical research has only recently been brought to light by Science magazine.

These decisions might mean the end of several important projects currently underway, particularly in immunodeficiency and HIV/AIDS research, which has benefitted tremendously from research conducted through stem cells.

Warner Greene, a professor at the University of California, San Francisco, and an HIV researcher, has been leading a projects that targets one of the most complex elements of HIV that has so far been resistant to therapy. The goal of the research, which Greene conducts in collaboration with NIH researcher Kim Hasenkrug and two more scientists, is to understand how the so-called latent HIV reservoir, or the non-active HIV cells that can at any moment turn active and increase the viral load, is seeded so quickly after an HIV infection. Based on their test-tube experiments, the scientists believe to have found the cellular substance that is responsible such reaction to HIV behavior and hope to test whether specific antibodies can stop it.

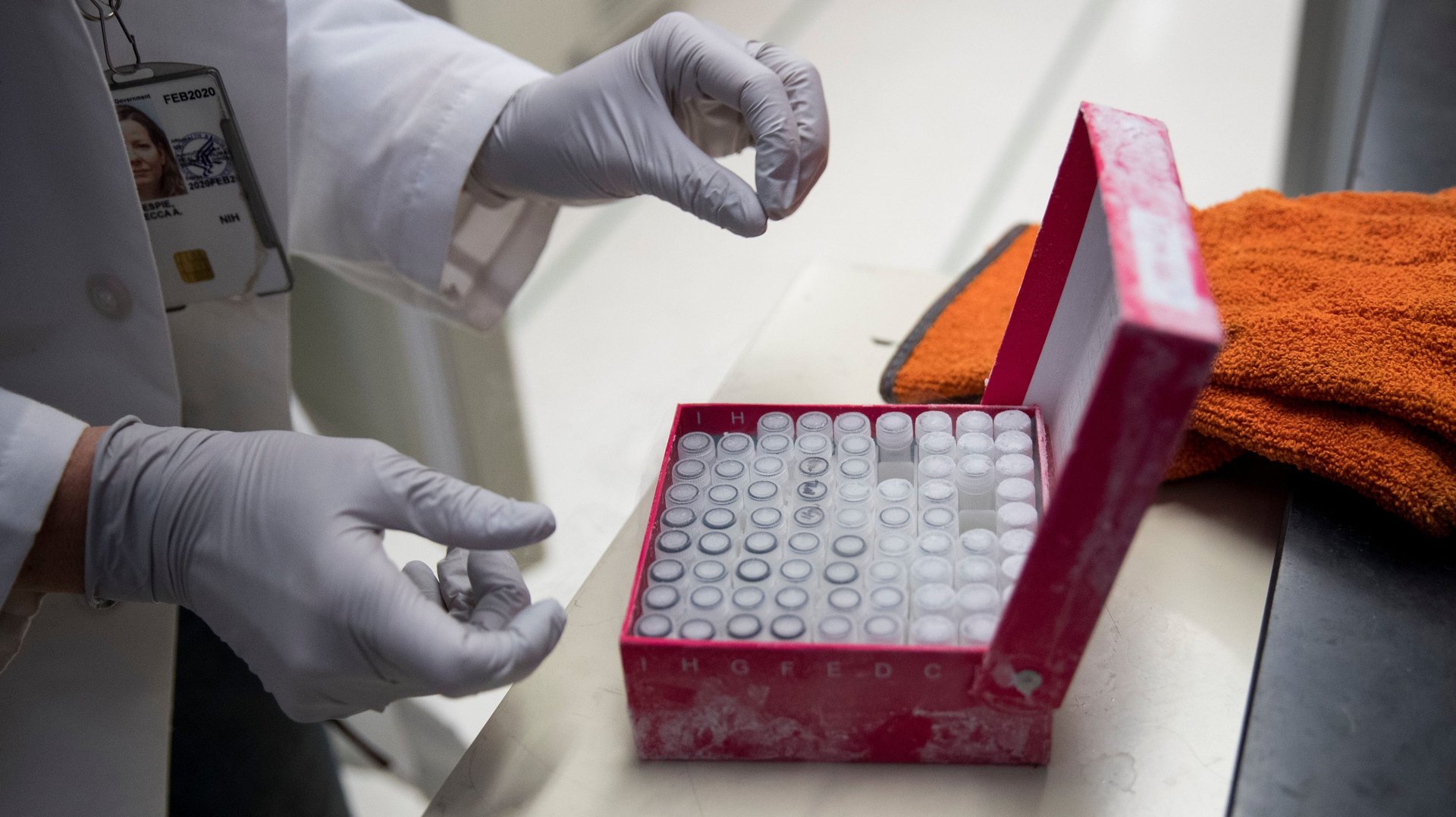

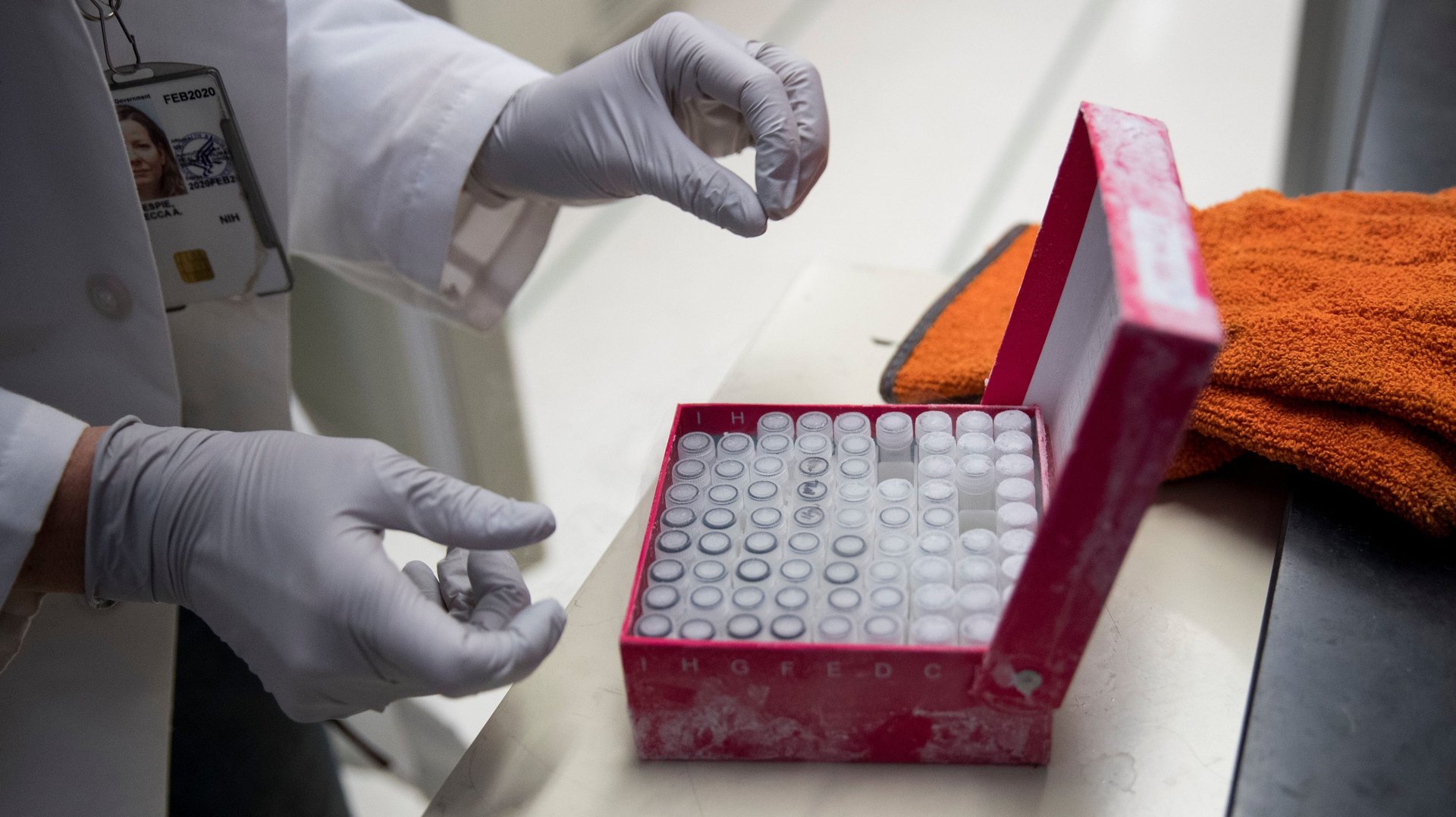

To do so, the experiment employs humanized mice—that is, mice whose deficient immune system had been replaced with a human-like immune system by grafting fetal tissue stem cells to the immune cells of a mouse. All the mice used in a specific experiment are genetically identical, and grafted with stem cells from the same fetal tissue, as the material from one fetus is sufficient to engraft 40 to 50 mice.

But the administration’s decision makes the research impossible to conduct, as no more fetal tissue can be procured: Though the first round of testing had started by the the time the new policy was announced, the team won’t be allowed to repeat the experiment. “Regardless what the results are,” Greene told Quartz, “we would want to replicate it once or twice.” Not being able to do so renders any results essentially pointless as scientific protocols demands results to be replicated in order for the findings to be considered valid.

There are essentially no good replacements for humanized mice, Greene says. The best option would be to use rhesus macaques—a monkey native to Asia—but they present some serious limitations. First, macaques cannot be injected with HIV, so the team would have to work with the primate version of the virus, the SIV (simian immunodeficiency virus). While they are similar, Greene says, the macaque and the human immune system are different, and the latter is more complex, so not all aspects of the virus behavior could be observed as efficiently as with mice.

Then there is a problem of cost: conducting experiments using rhesus macaques is extremely expensive, and it might take years to raise the capital and procure the animals to experiment upon. Finally, while experiments on mice can be conducted on twelve at a time, they typically don’t use more than three or four rhesus macaques at a time, which makes the experiment a lot less statistically significant.

So far, this ban is only referred to research conducted within government facilities, but it is unclear whether it will be expanded to outside experiments made in collaboration with the NIH.

Lawrence Tabak, deputy director of the NIH, said in a statement that the project’s halting was “due to a miscommunication.” Following the announcement in September, Tabak says, the NIH “initiated a pause in new procurement of human fetal tissue for a small number of projects by NIH scientists with the understanding that those projects had sufficient already procured tissue available.” However, he adds,”due to a miscommunication, one research project has been affected and we are taking steps to allow this project to resume and to avoid disruptions in other projects.”

Hasenkrug is scheduled to meet with HHS representatives on Dec. 18, when he hopes authorities will understand there are no good alternatives to conducting the experiments on humanized mice. “I think the NIH is very supportive of this line of investigation,” Greene told Quartz, “it’s been supportive [of it] for two decades.” But, he explains, his feeling is that the NIH is “on the one hand very supportive of the study, and on the other responding to pressure from above.”

Correction: Hasenkrug, not Greene, is scheduled to meet with HHS representatives on Dec. 18.