The “mother of all demos” was as much about the chair as it was about the computer

Fifty years ago this month, a shy computer engineer delivered a 90-minute presentation that’s now considered “the mother of all demos.” At the 1968 Joint Computer Conference in San Francisco, Stanford Research Institute’s Douglas Engelbart dazzled engineers with the incredible potential of a framework called oN-Line System, or NLS. Preceding the research by Xerox’s legendary Palo Alto Research Center and ARPANET, he showcased an early prototype of PC programs as we know them today.

Fifty years ago this month, a shy computer engineer delivered a 90-minute presentation that’s now considered “the mother of all demos.” At the 1968 Joint Computer Conference in San Francisco, Stanford Research Institute’s Douglas Engelbart dazzled engineers with the incredible potential of a framework called oN-Line System, or NLS. Preceding the research by Xerox’s legendary Palo Alto Research Center and ARPANET, he showcased an early prototype of PC programs as we know them today.

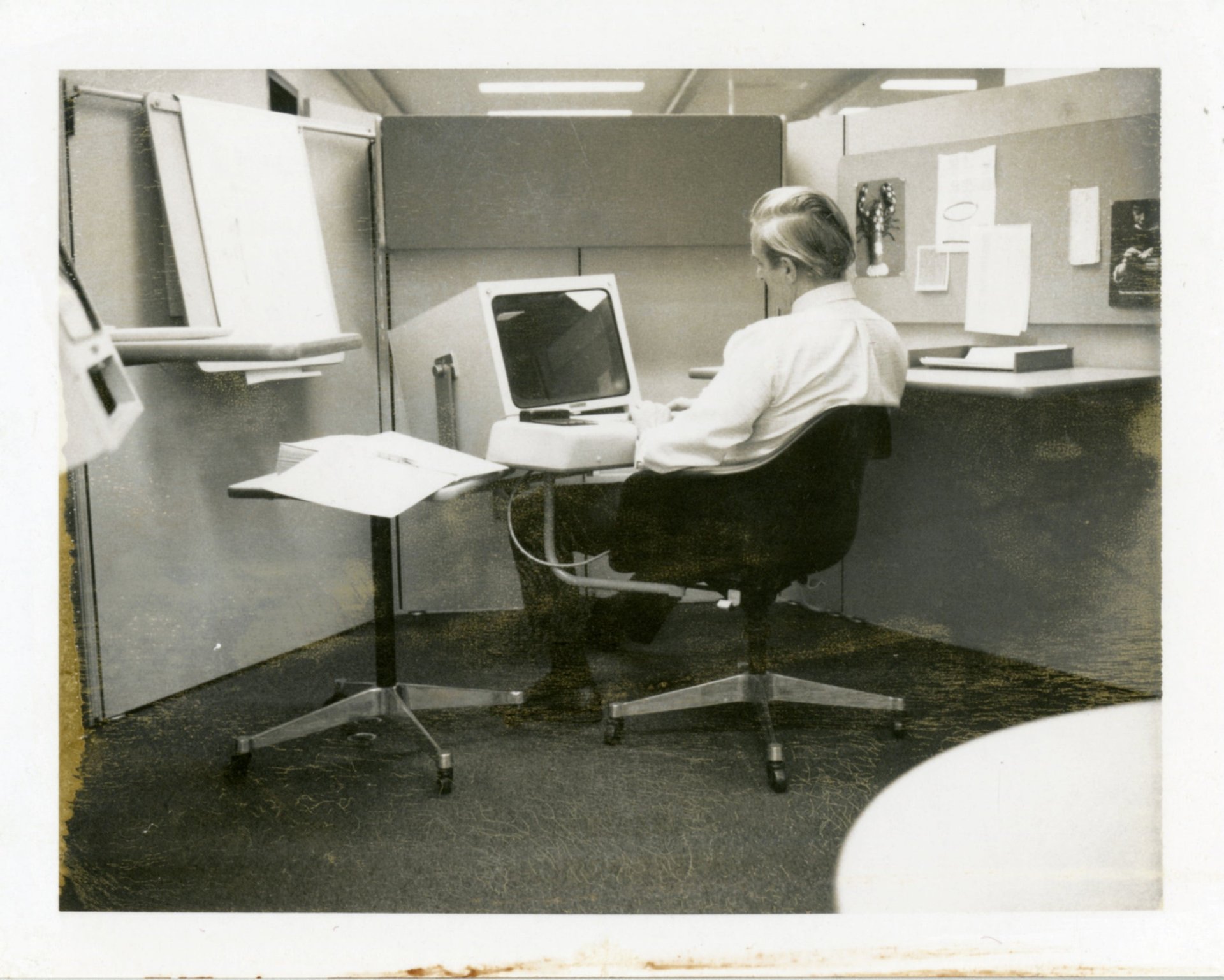

Using never-before-seen stage techniques, he demonstrated early versions of word processing, dynamic file linking, videoconferencing, the first computer mouse and, perhaps most importantly, he proved that individuals can use a personal computer comfortably for an extended period of time. In the mythic demo, Engelbart helped change the notion that computing machines had to be intimidating, room-sized mainframes.

“For all the horsepower and invention in the machine, which had its own large computational hub 40 miles away, it wasn’t the programming that made history. It was the interface,” writes tech historian Kristen Gallerneaux on WHY Magazine.

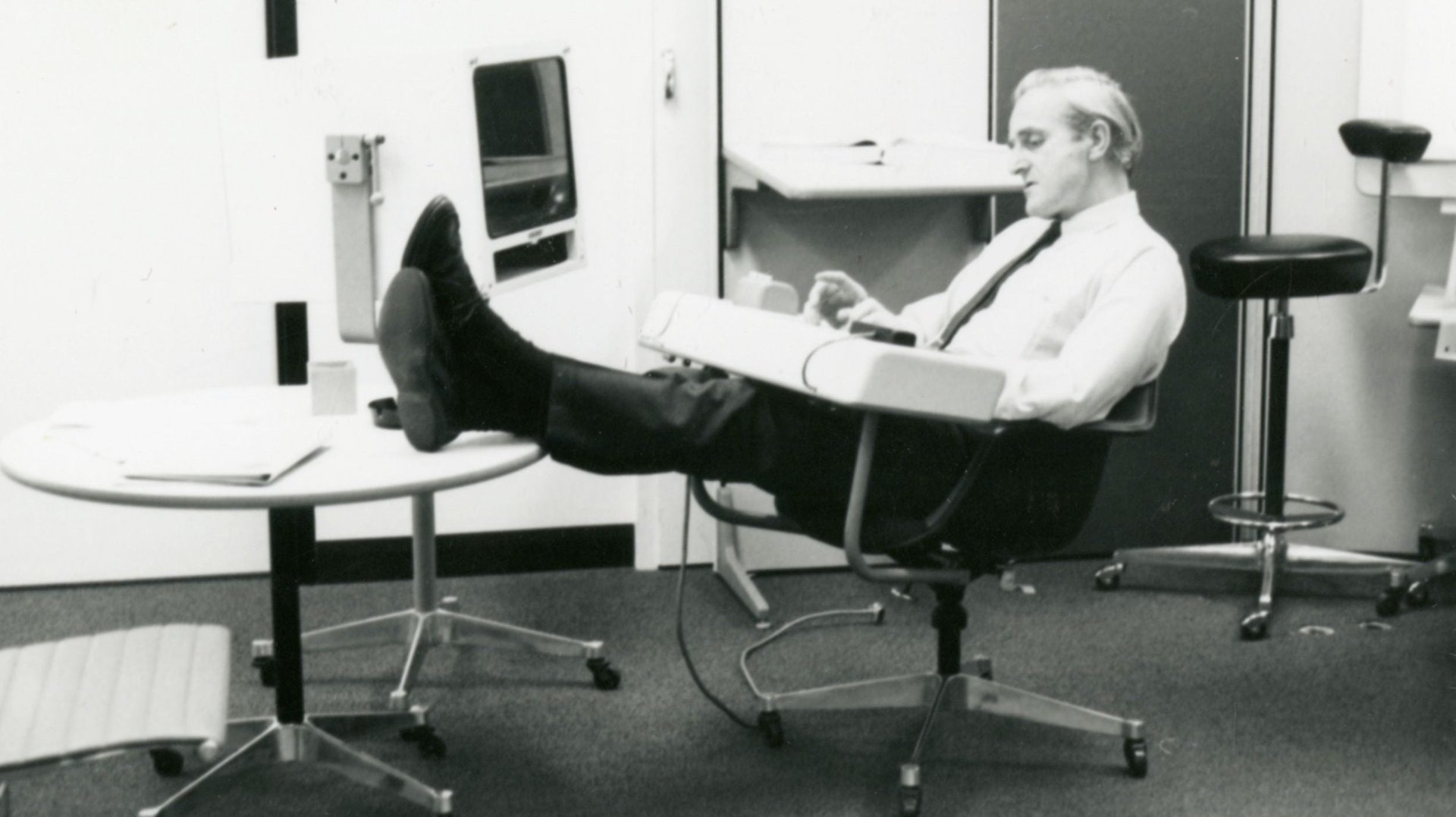

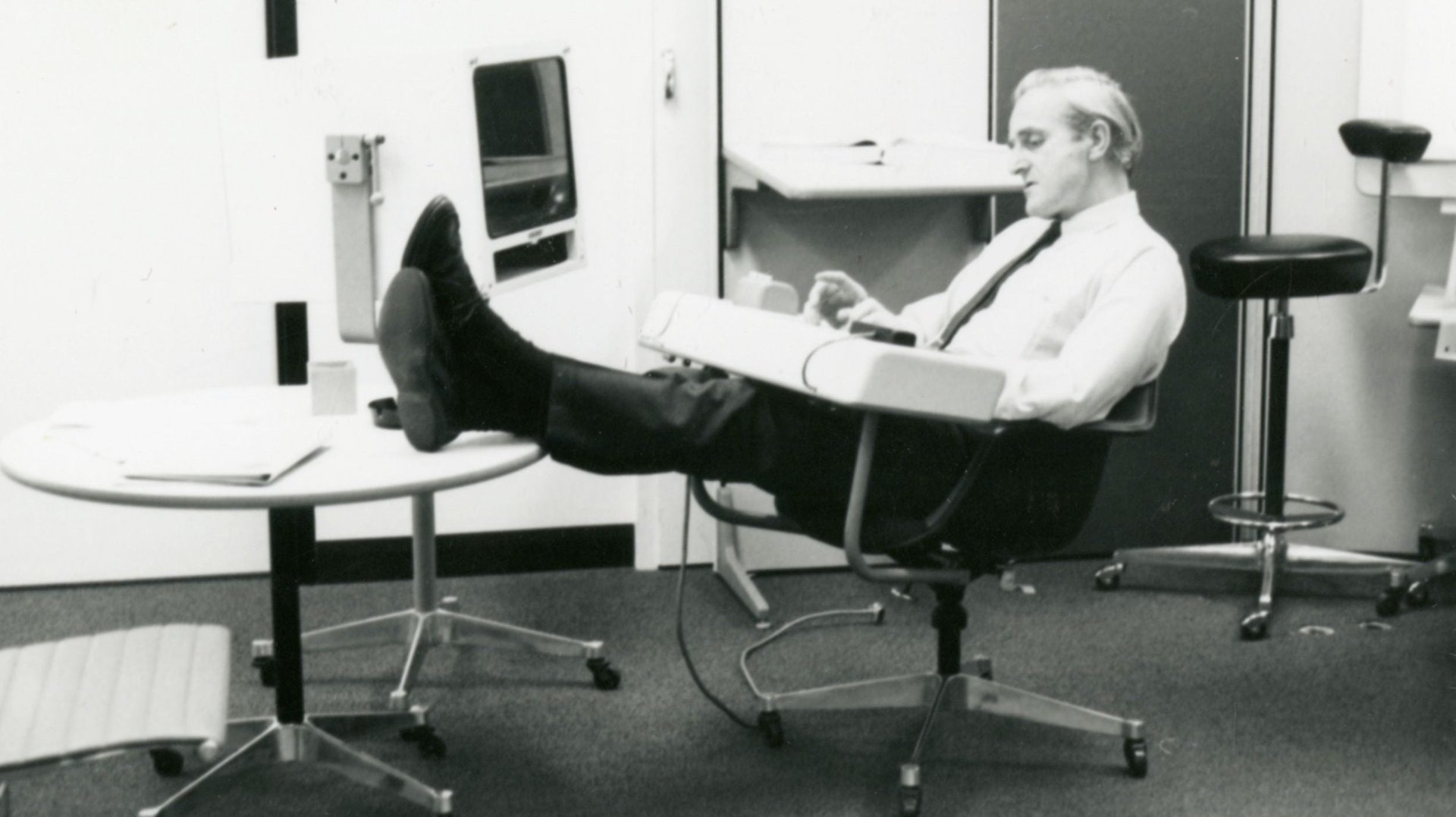

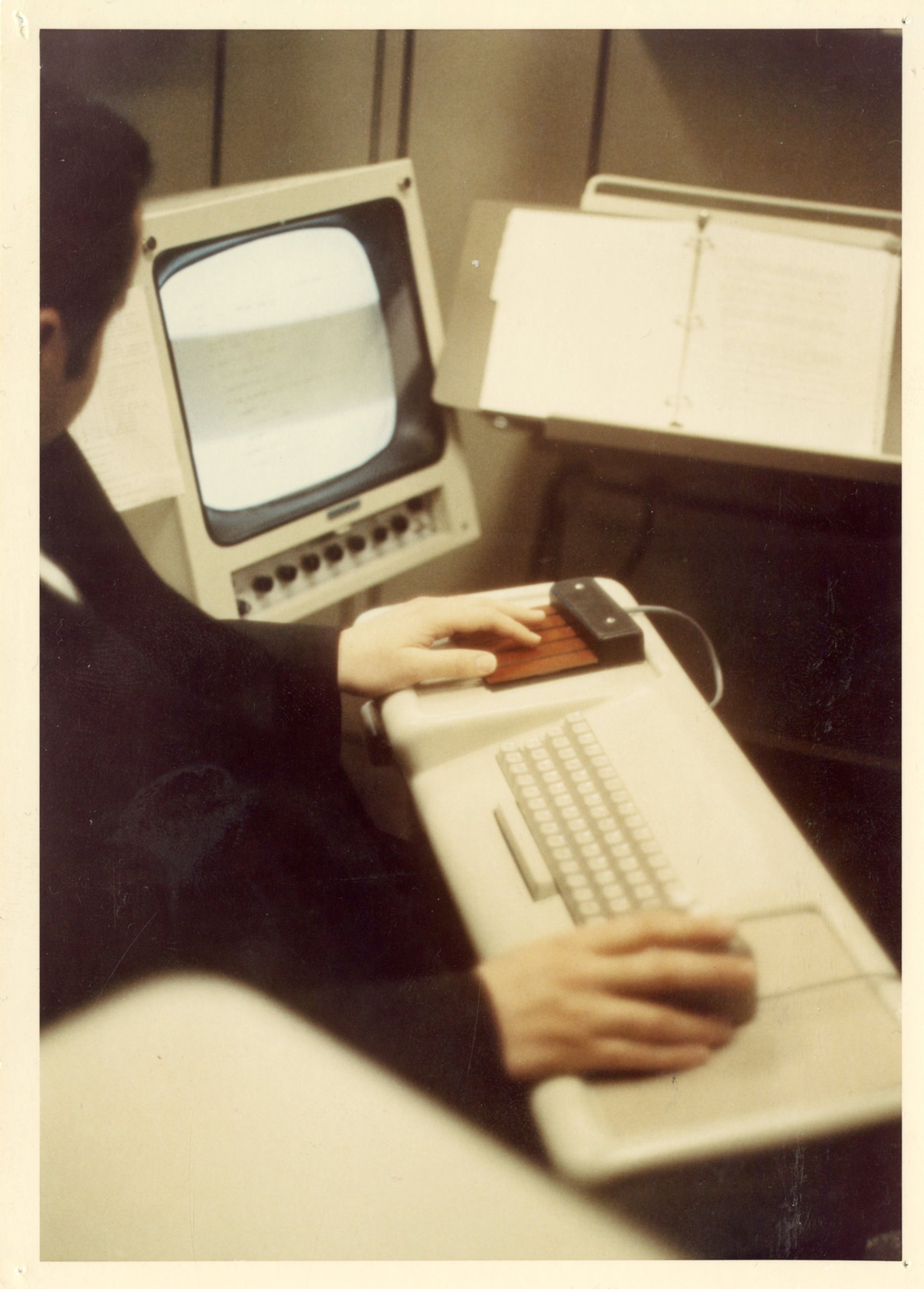

A crucial, but rarely discussed element of Engelbart’s stagecraft was his custom-built chair. Herman Miller designer Jack Kelley modified an Eames shell chair and affixed a detachable tray to house a keyboard, a computer mouse, and a keyset, which is a piano-like device Englebart invented for entering commands as you clicked the mouse with another hand.

Noting that the mouse’s tracking didn’t work well on the console’s hard plastic surface, Kelley lined the tray with a swatch of a synthetic leather called naugahyde. It would be the first mousepad made for the very first computer mouse. With user comfort in mind, it was also Kelley’s idea to unhinge the keyboard from computer’s main unit.

“The people who worked on computers were not so much concerned with design that the human body needs,” Kelley explains to Quartz. “Computer geeks were focused on creating simplified systems. The lure of technology just bypasses the needs of a human being using the device.”

Prior to the seminal demo, Kelley also worked on the interiors of Englebart’s lab at the Stanford Research Institute (now SRI International). There, he deployed Herman Miller’s new “Action Office” system, a groundbreaking design and manifesto for flexible office plans conceived by the company’s then head of research Robert Propst. Before ergonomics became the buzzword of the furniture industry, Kelley, who worked under Propst, was designing for “work vectors,” which considered various body postures office workers had over the course of the day.

“By using the language of Action Office, Kelley’s work on the console chair and mousepad allowed NLS to evolve from technological curiosity into the centerpiece of a living, dynamic work setting,” explains Gallerneaux.

“I designed the computer chair with a swing-out console because Englebart liked to work in different attitudes and statures … stand-up, sit down, relax. … How do you solve for that?,” says Kelley, who attended the demo’s rehearsals. “But all the excitement went to the computers.”

Kelley, who is now retired, says he’s become somewhat of a tech nut after working with Englebart in the 1960s. So what does he think of today’s tech demos? “I think Apple is doing it right,” he says. “They’re humanistic and paying more attention to the design detail. They’re using technology to resolve a design detail and talking about users, which is a big change.”

The physical set-up for the “mother of all demos”—with Kelley’s hacked Eames chair and console at the centerpiece—is now enshrined at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California.