Zero-fee funds are making some investors even more nervous about 2019

The best things in life are free, except maybe index funds.

The best things in life are free, except maybe index funds.

An important new milestone was reached in American financial markets this year: For the first time, a financial company—Fidelity—offered a mutual fund that didn’t charge management fees, the first zero-fee funds.

Over the last 20 years fund fees have been trending down as more investors have discovered the benefits of passive investing, a strategy where a mutual fund is assembled out of stocks according to their placement in a pre-specified index. After years of charging investors high fees to select their stocks, investment managers are now racing to offer the lowest fees. Now, as actively managed funds are falling out of favor, some asset managers and economists are wondering if this is too much of a good thing.

How we got to zero

Management fees have fallen because of one thing: index funds. But to understand index funds, you need to know the history of mutual funds.

During the first half of the 20th century most Americans owned a few dozen stocks they picked themselves. That changed in the 1950s after Harry Markowitz, an economist at the University of Chicago introduced modern portfolio theory. Markowitz argued that if investors owned lots of stocks they could eliminate idiosyncratic risk (the risk a single stock will rise or fall). More over, if they owned the right combination of stocks (or even other kinds of assets) they could get bigger returns for less risk—the finance equivalent of a free lunch.

This idea, coupled with advances in computing and better data, sparked the growth of the mutual fund industry. Professionals searched for the perfect combination of stocks that promises higher returns for less risk, then sold access to the funds to retail and institutional investors. Picking the right stocks is difficult, so funds could justify charging investors 2% of the value of their assets or more in management fees. Meanwhile, in 1964 academics discovered the most efficient portfolio was not handpicked; rather, it was holding all the stocks in the market, or a subset of the market, such as the companies in an index like the S&P 500.

Researchers estimated an index fund usually beat the active funds after accounting for fees and risk. These passive funds don’t charge the high fees because there are no humans (or talent) involved in picking stocks, a presumed skill that commands huge salaries. The first index funds were offered to a few institutional investors by Wells Fargo in the early 1970s. A few years later, in 1975, Jack Bogle founded Vanguard, which offered index funds to retail investors.

For years, most people ignored the advice of economists. The temptation that you can get rich with extra insight or ability was just too appealing, and most investors would put their money in active mutual funds. This started to change in the 1990s as more Americans owned stock through their 401(k) plans or other kinds of retirement accounts and there was more education, transparency, and awareness about fees. Individuals also began to seek out advisors who were paid a fee, rather than a commission based on how how much the funds cost. The creation of exchange traded funds (ETFs)—index funds that are traded on an exchange—made the funds more accessible. The financial crisis, and a growing mistrust in financial professionals, may have also played a role in the rise of the index fund. These factors led to an uptick in index fund growth in the last 10 years.

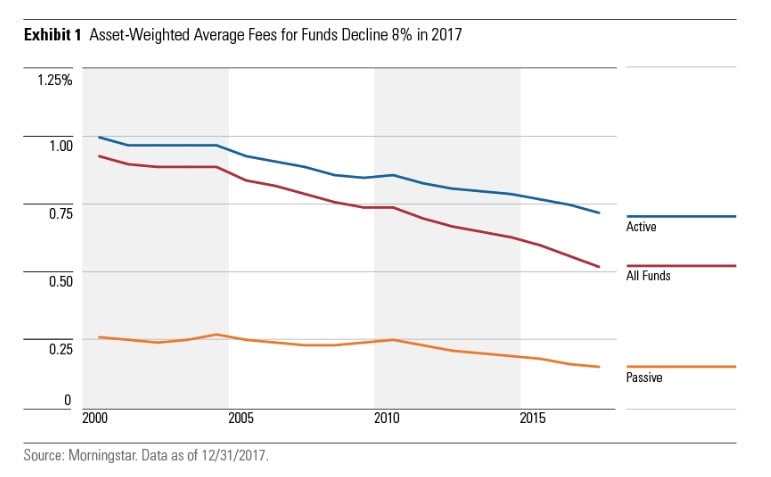

Index funds now make up almost 20% of assets in mutual funds. More money in cheaper, passive funds lowered the average fee paid for both active and passive mutual funds. According to report from Morningstar the average management fee fell almost 45% since 1996.

Initially, the average fee fell because more people embraced passive funds. But as investors became more conscious of the fees they paid, it put pressure on active funds to charge less, too. Now, even passive funds are undercutting each other, charging less than 0.10% or, as in the case of Fidelity, nothing at all. Management fees have sustained the asset management industry for decades. The idea that it’s not worth paying someone to pick stocks threatens their business model. No wonder there has been a backlash.

The dangers of index investing

The first serious concern about indexing is that it makes markets inefficient. Active investors research stocks, then buy shares in companies that are performing well and have good prospects. They sell shares in companies who are failing. This process ensures productive and profitable companies have access to capital. But in indexing, there is no research. If a company makes up 3% of the index, it makes up 3% of the index fund, regardless of what investors think of its earnings potential. In index funds, capital goes to the biggest companies, not the most deserving. Another concern is markets will become more volatile, with more systematic risk, because all stocks will move together when index investors buy or sell their shares in a fund.

There are reasons to be skeptical of these arguments. First of all, the rise of index funds coincided with one of the most stable periods in market history (even including the last few weeks). Second, they still only make up less than 20% of the mutual fund market. There’s still plenty of people picking stocks and doing research.

A large share of the financial industry is invested in active stock picking, so it is not surprising there would be pushback from people who have lots to lose. Which is why a recent essay from Bogle, whose Vanguard is the original provider of index funds, raised concerns. Bogle worries there are too few index fund providers, which means control over corporations will be concentrated in the hands of a handful of giant fund managers. “If historical trends continue, a handful of giant institutional investors will one day hold voting control of virtually every large US corporation,” Bogle warns.

One outcome is that large passive investors may not be as invested in the performance of a single company as asset managers who have more riding on the performance of one company. In that scenario, they may not exert as much oversight and pressure as active investors.

Bogle says the tipping point will be when 50% of the market is invested in index funds. But there are reasons not to worry. One study, published in the prestigious Journal of Finance, argues passive funds do influence corporate governance. Sometimes big institutions are the most effective at pressuring boards to do stuff. State Street and BlackRock, two of the biggest fund providers, have frequently voted to make corporate boards more diverse and have been skeptical of executive pay and treatment of the environment. BlackRock’s Larry Fink has argued that because passive funds represent long-term investors, indexing could result in firms making more long-term decisions and become less captured by short-term interests.

It is also a big leap to worry about a 50% index market. The market for index funds may have been growing, but it is started to level off. Indexing makes sense for retail investors, like retirement accounts or everyday savers, but they only make up about 50% of the stock market. Institutional investors, the big companies that manager endowments and pension funds, continue to dominate the market and account for 70% trading volume. They still have an incentive to invest in active funds. Their chief investment officers are paid to do things that beat the market, like pick stocks or move money into alternatives assets, and they are not going anywhere anytime soon. They also sometimes have legitimate reasons to invest in active funds, such as when some institutions place restrictions on how the funds are invested, ie. not in tobacco, and active management is necessary to achieve diversification.

Peak low fee

There have been many benefits to lower fees. Investors, especially individuals saving for retirement, can get all the benefits of diversification with less cost. That means more wealth for them and less risk. But there are reasons to be concerned by low-fee and free funds, because they can lead investors to take on more risk than they realize.

Nothing in life is really free. Fidelity is willing to take a loss on the funds by not charging fees because they hope to earn fees from those same customers on their brokerage platform. But if there’s a race to the fee-bottom, we can expect other fund providers to make money the normal no-fee way, through securities lending. Funds will lend securities to speculators who want to short stocks and make it profits off the loans, and charge low or no fee to investors. Most of the time this will work, but if there’s an extreme market event and borrowers can’t return the shares, investors may not be able to sell out of the fund when they need to (which tends to be extreme market events). Investors in the fund pay no fee in exchange for taking on the risk of a big, market shattering event.

It is also important to remember that index funds only reduce idiosyncratic risk, such as one company failing, but it does not help with systematic risk, or the risk the whole market will crash. Reducing systematic risk requires investing in lower-risk assets, like a bonds, or buying insurance, like annuities. Often, you are asking someone to take risk on for you, and you must pay a fee for that because taking on a risk poses a cost to the insurer. Picking a fund with the cheapest fee is a fine strategy to select a risky portfolio, but dealing with market risk takes planning or insurance, and that will always cost something.

This article has been updated to clarify no-fee funds are new to US financial markets.