On the 50th anniversary of Earthrise, a NASA astronaut describes how far we have to go

Astronomers have spent centuries pointing their telescopes toward the stars. But it wasn’t until 50 years ago that we got to look back down at ourselves from space.

Astronomers have spent centuries pointing their telescopes toward the stars. But it wasn’t until 50 years ago that we got to look back down at ourselves from space.

On Christmas Eve 1968, NASA astronaut Bill Anders took the now-famous Earthrise photograph while aboard Apollo 8. Technically, it wasn’t the first time Earthlings had seen their planet from space; that accolade went to some black-and-white robotic probes a few years before. But it was the first time that we collectively recognized how incredible, and how fragile, we were floating out there in the cosmos—a statistical marvel in the middle of the Milky Way galaxy, a happenstance of swirling gases and elemental particles.

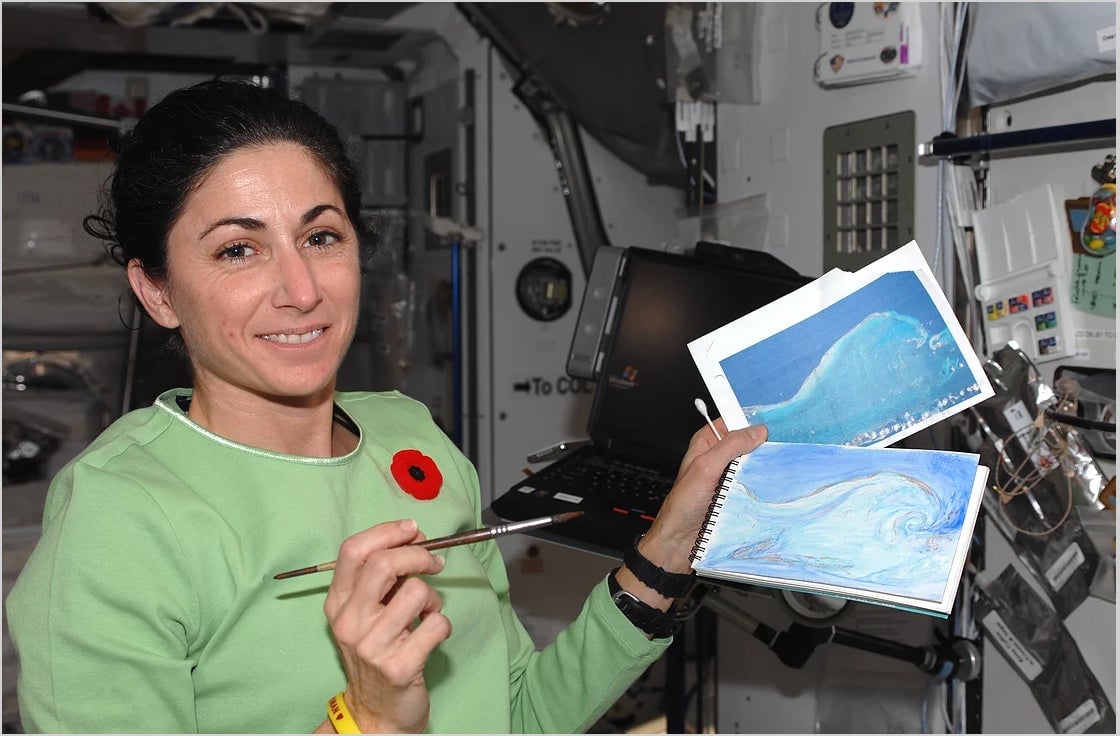

Nicole Stott was 6 years old when the photograph was taken, and nearly four decades later, she got to see the planet for herself. Stott was a NASA astronaut for 15 years, spending months at a time living on the International Space Station (ISS), gazing back on the rock she calls home. A keen painter, when she retired from spaceflight a few years ago, she began using art to promote keeping Earth habitable and hospitable. (Stott is also the first person to ever paint in space, which is a truly intergalactic claim.) Now she continues to champion these narratives through Constellation, an organization that uses interstellar stories to inspire local change.

Ahead of the 50th anniversary of the Earthrise photograph on Dec. 24, we spoke to Stott about how the world (and the universe) has changed since then. In this lightly edited and condensed interview, Stott takes us on a journey beyond the thin blue line of our atmosphere—and then brings us catapulting back to the realities of the planet we must share and protect together.

Back in 1968, what do you think the public thought when they first saw the Earthrise photograph?

My impression of the image is this undeniable reality check of “Oh my gosh—we live on a planet.” It’s seriously simple stuff. The same thing that happened when I flew in space myself: I knew what to expect, but suddenly [Earth] was in my face in a way that I had never seen before. And not just as a planet hanging there by itself. There is a strange interaction between this planetary body we know as our home, rising up above the horizon of some other planetary body in space.

Even now, I look at that and I’m like, “That is the who and where we are.” We live on a planet; we’re all Earthlings. The only border that matters is that thin blue line that blankets us all. That’s undeniable when you look at that image. It’s that kind of connection we want to make as human beings back to ourselves.

It happens to us all on the space station. All of a sudden you’re like, “Wow, I didn’t think I was coming here to figure out that I live on a planet.” The Apollo 8 astronauts expressed it the best: “We came all this way to explore the Moon, and the most important thing is that we discovered the Earth.”

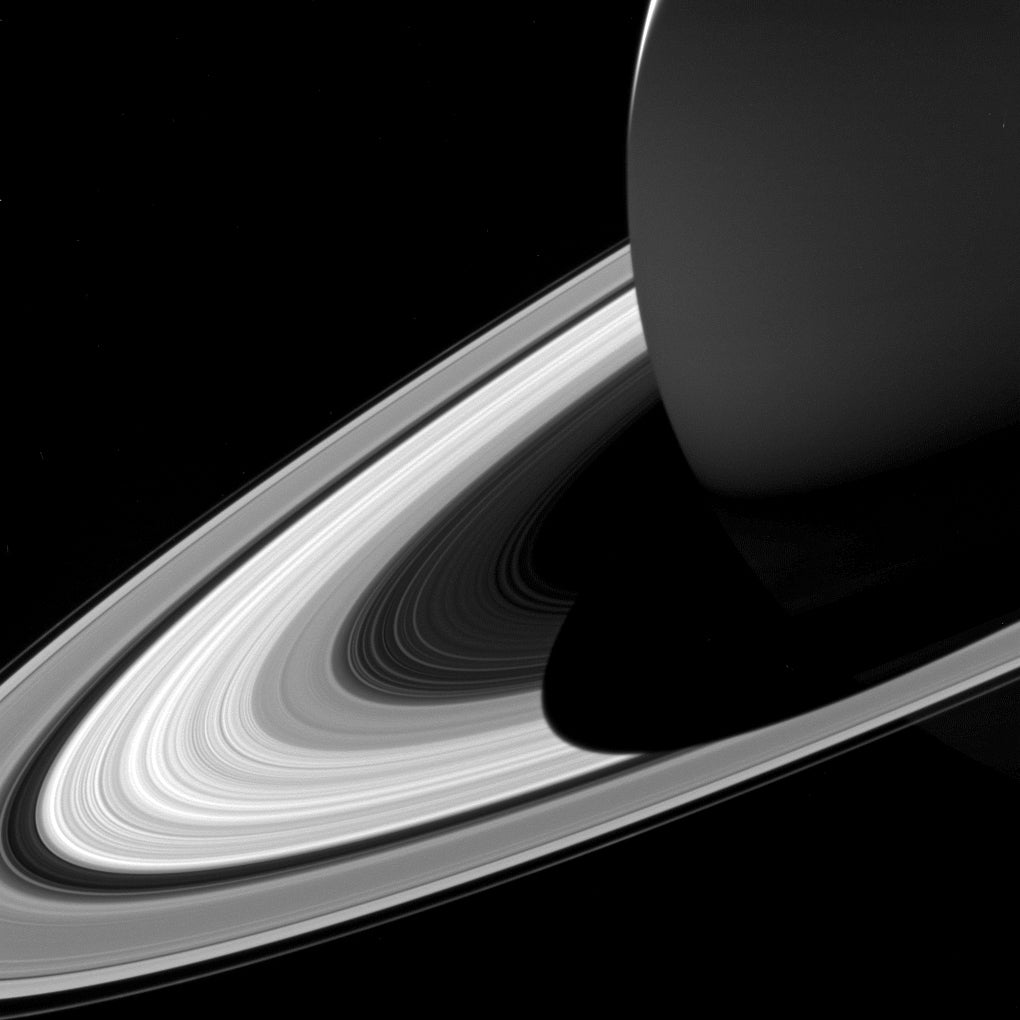

That’s why all of this is so important. There is a relationship between space and us. And we can define that so easily through the Earthrise image. It’s a very human thing. Ultimately, whether we’re going to Saturn or we’re going back to the Moon or onto Mars or wherever else, it really ends up being about improving life here on Earth.

That’s exactly what [fellow former NASA astronaut] Ron Garan said when I interviewed him last year. He said that as soon as he looked back on Earth from space, instead of being wowed by the universe, he realized how beautiful Earth was. “What am I doing up here when there is an amazing, beautiful planet down there?” So now he’s doing environmental work to help save Earth rather than decamping to Mars.

Ronnie and I are really close friends—he and his wife are my son’s godparents! We talk about this stuff a lot. I’ve come to conclusion that maybe the way we talk about the planet needs to change a little bit. We need to think about it more like a space ship. We need to start treating and operating it in a way that’s similar to what we do so peacefully and successfully on the space station. That could be such a wonderful guide for us.

The ISS is a purpose-built machine for space, but it’s all about mimicking what Earth does for us naturally. We establish this closed-loop system where we have to do things very deliberately so we can breathe clean air, have clean drinking water, and generate our electricity. It’s about [creating] a life-support system, and about keeping the humans beings that live there alive.

That’s what Earth does for us, too. But we don’t think about the way we have to operate here [on Earth] collectively as crew mates. We need to start thinking about how we can protect this closed-loop system that keeps us alive.

I think people might relate to that better than “save the planet.” Because what we need to save about the planet is the things that keep us alive. The planet has survived a lot worse than us before.

We’re giving it a good attempt to screw it up, though.

Yeah, and if we continue on this not-very-productive path, I honestly believe we’ll be the ones gone, not it. It will survive us. We’ve been a blip so far in the history of Earth. It’s up to us to choose how we work together and how we operate these systems.

So we should treat our time on Earth with the same level of care and consideration as you guys have to on the ISS, whether that’s conserving drinking water or not wasting energy. We don’t give Earth that same consideration, do we?

No, we don’t think about it that way. I like to equate the thin blue line of the atmosphere to the thin metal hull of the space station. We are totally aware and deliberate about making sure that the metal hull is protected, but we don’t think as much about the thin blue line surrounding our spaceship Earth. It’s crazy. We are doing everything we can to avoid a hole in the side of our spaceship, where all the air will go spewing out into the deadly vacuum of space. And if we’re not careful, that’s the kind of thing we’re doing down here on Earth.

If I think if I heard more media campaigns threatening the “deadly vacuum of space,” I might consider plastic straws differently.

I know! It’s a matter of how we communicate with each other about things, isn’t it? And sadly there is a selfish motivation. If it’s my butt that’s going to be saved, then I’ll do this thing—but if it’s the planet’s butt, then not so much.

I was out at a conference recently where Jo Huxster did this really great job talking about how we should communicate about climate change. She put up a slide of a polar bear on this tiny little piece of ice, out in the middle of the ocean… except it had a big X through it. She said it’s not because she doesn’t love polar bears—but putting the polar bear on the floating piece of ice that’s so far away from anyone you’re trying to communicate with is not going to be the way to get them to maturely respond to what’s going on. It’s got to relate to them.

It also gives you the sense of the polar bear being beyond lost at that stage. If you can’t save that polar bear and things are too far gone, some people will question, “What’s the point in even trying?”

I don’t think that’s where we’re at yet. People before us, like Buckminster Fuller, really did think of Earth as a spaceship. We need to put together an operating manual for all of us. All of us need to be crew members, not passengers—and even worse than that, you shouldn’t be a tourist. We shouldn’t think of ourselves as tourists on the planet.

It’s up to us. I know Ronnie likes to say, “There is no us or them. It’s all about we.” Going back to Earthrise, that is one thing you cannot deny. There is no other side of the planet. But when you look at a polar bear sitting on a little floaty piece of ice, you may feel sad for the polar bear, but he’s so far away that you don’t think he impacts you; it’s difficult to make the connection between how plastic straws ultimately impact the polar bear—or you.

Whether it’s Earthrise or the polar bear, these kinds of images can express concepts to people in a visual way. You’re an artist yourself. What role does art and photography play in helping us express science concepts?

Art is this universal communicator. When I was thinking about retiring from NASA, we all want to find our unique way to communicate the space-flight experience. To me, art made the most sense. I can share something that people already love, and then the backstory can come from it.

We’ve been using art as a way to communicate science forever. Like astronomical imagery. Even if the scientists don’t think they’re being artistic, when they do a full colored image of the ones and zeros that are coming back from the Hubble space telescope, that’s so they can get their brain wrapped around it, too—they can understand which gases make up that nebula by making them different colors. Then the rest of us think it’s just an amazingly stunning, beautiful picture of this thing out in the universe.

I think human beings are attracted to that kind of visual, maybe even audible experience: to become attached to something, and consider it important. You cannot deny the beauty of the Earthrise image. But the ultimate thing about it is that it’s us. And we just hadn’t seen ourselves that way through any human eyes before. There is real power in that.

If we could photograph something in 2018 that we’d be looking back in 50 years’ time with the same awe we do with Earthrise, what would it be? Or, as you said, what might we hear, like how we could represent the discovery of gravitational waves through sound?

That’s pretty cool. But I think there’s just something about those Cassini images—they always come to mind for me. About how far off in our own solar system we are. We haven’t gotten people there yet—and maybe in 50 years, we will have. But to look back at these early days of this kind of exploration, where we can see ourselves in images like that? Even if it’s a tiny dot of light, you know it’s us. We’re over the horizon of this ring of Saturn versus over the horizon of the Moon, but it’s still us.

What about something that we haven’t captured yet? Like a galaxy you love, or the inside of a black hole. What would you like to photograph that no one has ever seen?

As a kid, I have this memory of sitting on my bedroom floor with this National Geographic magazine that was about space. It was a really cool issue. At the very center of this one they had this full four-page foldout that was of the observable universe. It was this really beautiful drawing, and I remember looking for us. Where’s Earth in this picture?

But it was this oval-shaped drawing on a piece of white paper. The oval had this very stark edge. And I remember looking it and thinking “… what’s all this white stuff?” The white on the border, on the paper. I remember thinking that the white stuff rolled right onto the carpet and across my bedroom floor. And I’m looking out the window, thinking how far this thing goes. Is the white stuff just what we haven’t discovered yet? Is the white stuff heaven? What is it?

It was mind boggling to me, and it still is. It was one of those things where I was thought, “We know what we think we know about who we are.” And what is all this white stuff? Is that what infinity is? We have this concept of infinity—but really what does that really mean?

So the picture I would like to see is the oval in the grander scheme of the universe.

I don’t know about you, but I don’t have many really vivid memories like that. That’s one of them that stands out. It just absolutely stands out. I still think about it to this day. Who knows if we’ll ever know what the white stuff is. And maybe that’s okay.

To celebrate the Earthrise anniversary, Stott, Garan and other Constellation astronauts will be leading a launch event on Dec 21 at the Kennedy Space Center—the location where Apollo 8 was first launched from. For tickets and to learn more, click here.