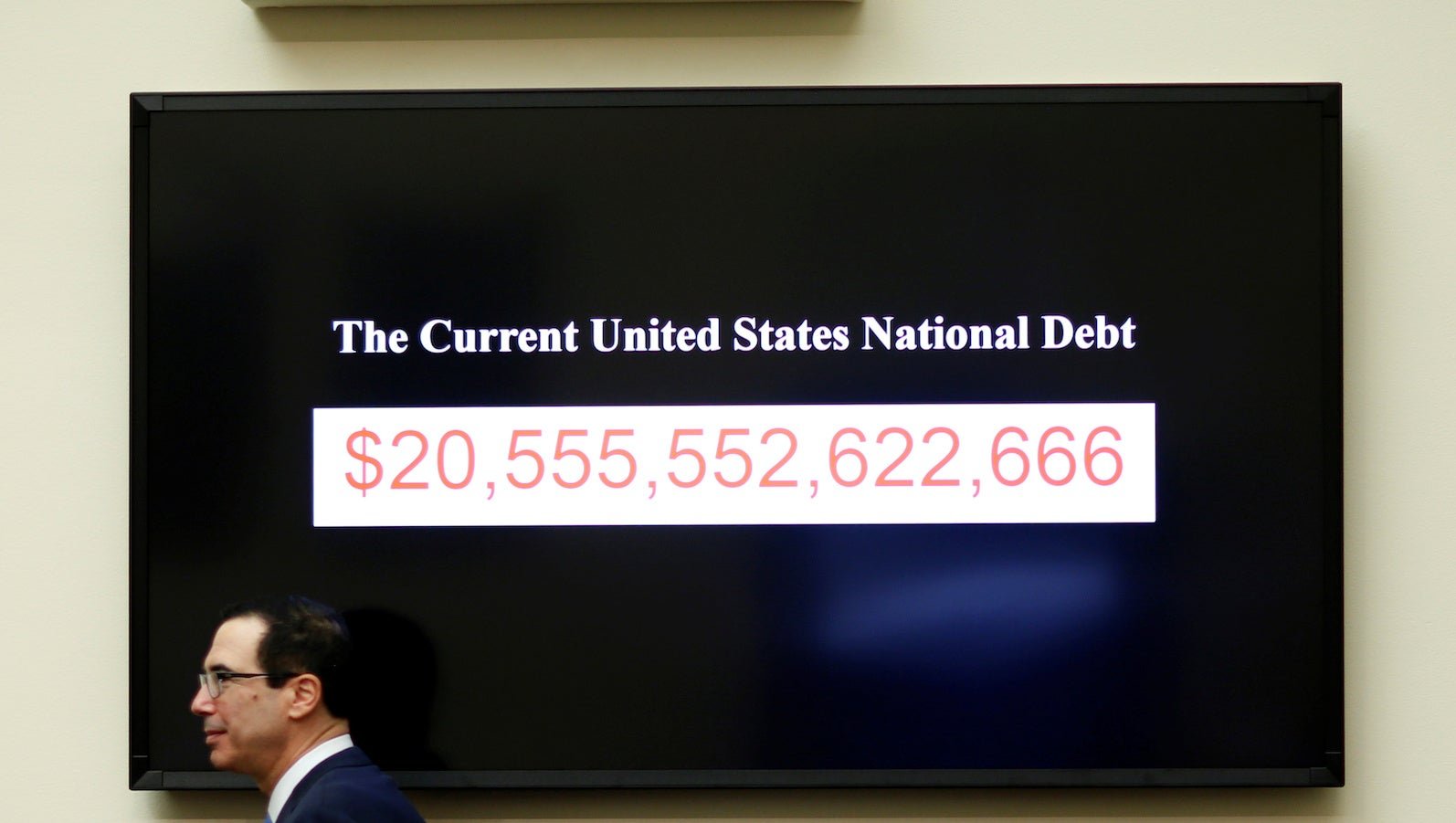

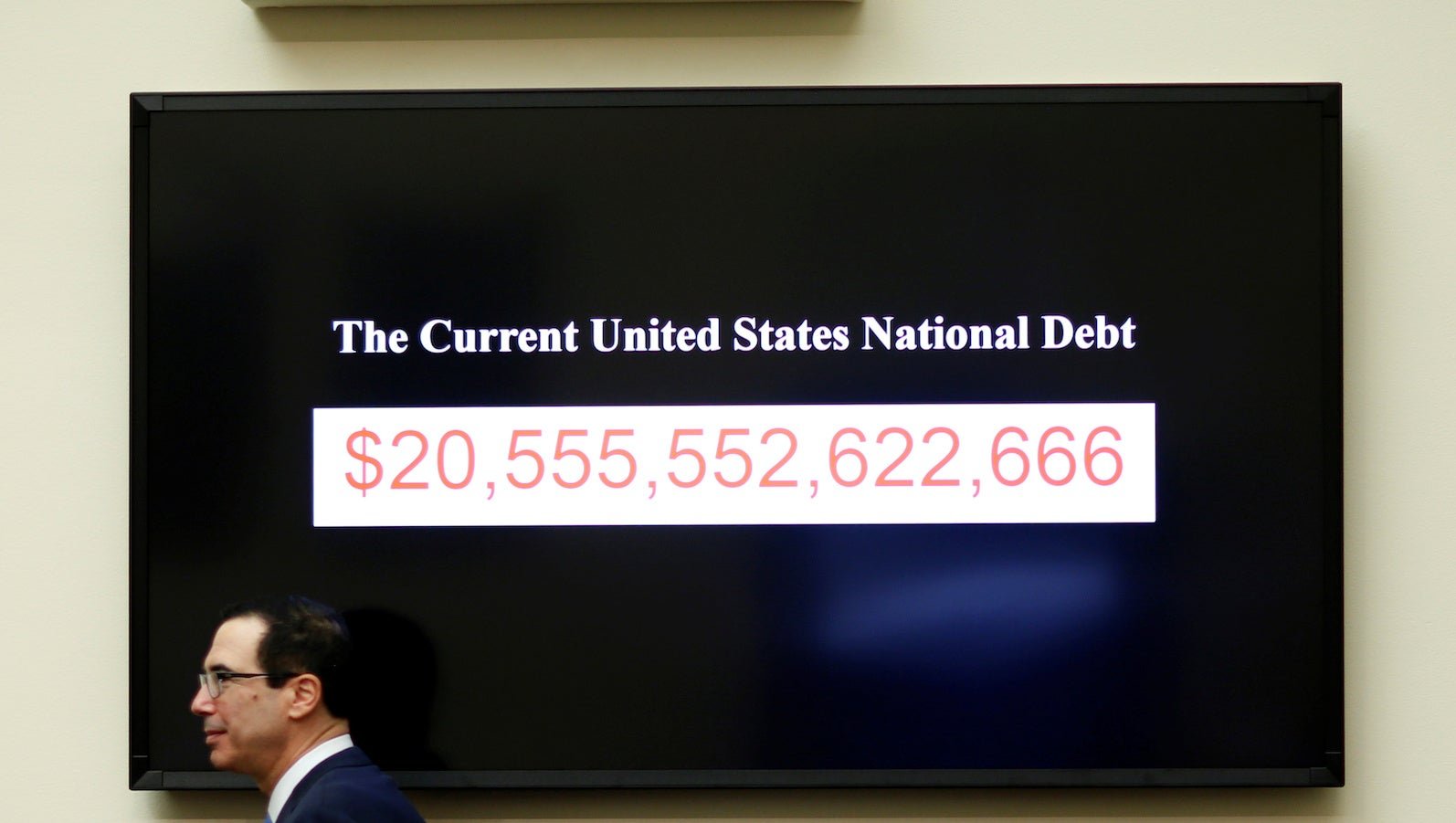

The rise of private equity has left us with a lot of worthless, dangerous debt

Private equity (PE) is booming.

Private equity (PE) is booming.

The practice of taking pools of capital (derived from pension funds and very rich people) and deploying it in funds to acquire ownership of companies—often by taking public companies private and running them better in the hopes of selling them off for a significant profit—is going from strength to strength. Private-asset managers raised a record of nearly $750 billion globally last year, according to McKinsey and Co.

That included a jump in so-called megafunds, which contain more than $5 billion. Those now account for 15% of all US private fundraising, another record, according to the consultants.

And what has that left us with it? A lot of terrible, low-quality debt.

PE firms usually like to fund their takeovers with leveraged buyouts, fueled by debt. The top 10 ratings on Moody’s credit-rating scale range from Aaa to Baa3 and are considered “investment grade,” which means from there’s an excellent-to-good chance you’ll get your money back. The bottom 11, from Ba1 to C, are junk.

According to a recent Moody’s report, 90% of the debt issued out by private equity is rated B2 or lower—the bottom seven ratings, one of which includes being in default. Why are investors tolerating all this no-good debt? Well, it may be terrible—but because it is so terrible, it pays a lot of interest.

Leon Black, founder of PE firm Apollo Global Management and a key player in Michael Milken’s Drexel Burnham Lambert—which practically invented the high-yield debt market in the 1980s—said recently at a Goldman Sachs conference, as reported by Axios: ”The credit markets, unlike the equity markets, have gone to bubble status. You have a thirst for yield that exists on a global basis. So there is true excess.”

In a world of low-interest rates, investors have been taking more risk to get more return on their investments. Black noted the amount of “covenant-less debt is more than 2007,” when the last financial crisis kicked off. Covenants are usually standard investor protections built into this kind of debt, which were removed from more deals as investors got more complacent prior to the last crisis.

As markets seesaw and interest rates return to normal, Black’s warning of another credit bubble—and the hundreds of billions of worthless debt that could come due if the bubble bursts—should feel a tad ominous.