Suicide rates are falling almost everywhere in the developed world but South Korea

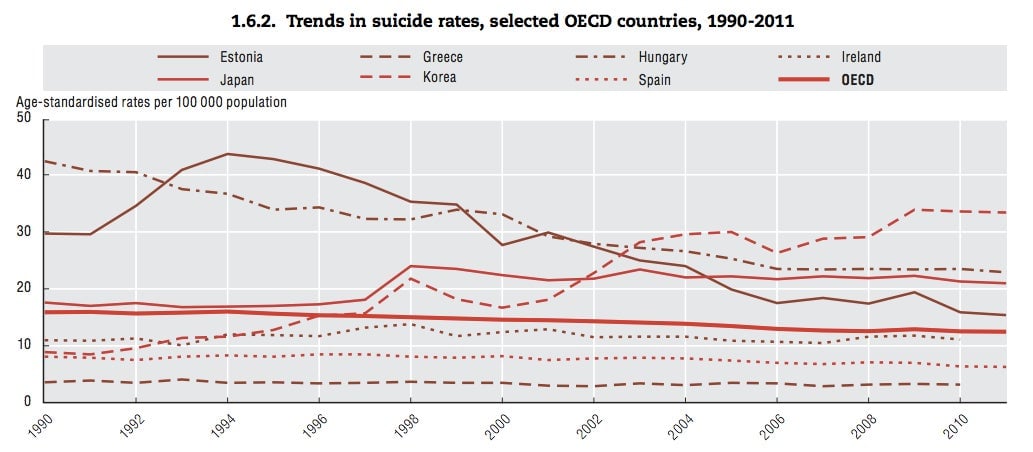

Last month, the South Korean government released some encouraging news. For the first time in six years, suicide rates had fallen in the country that’s long been known as the suicide capital of the developed world. There were 28 self-inflicted deaths per 100,000 people in 2012, an 11% decline from the year before.

Last month, the South Korean government released some encouraging news. For the first time in six years, suicide rates had fallen in the country that’s long been known as the suicide capital of the developed world. There were 28 self-inflicted deaths per 100,000 people in 2012, an 11% decline from the year before.

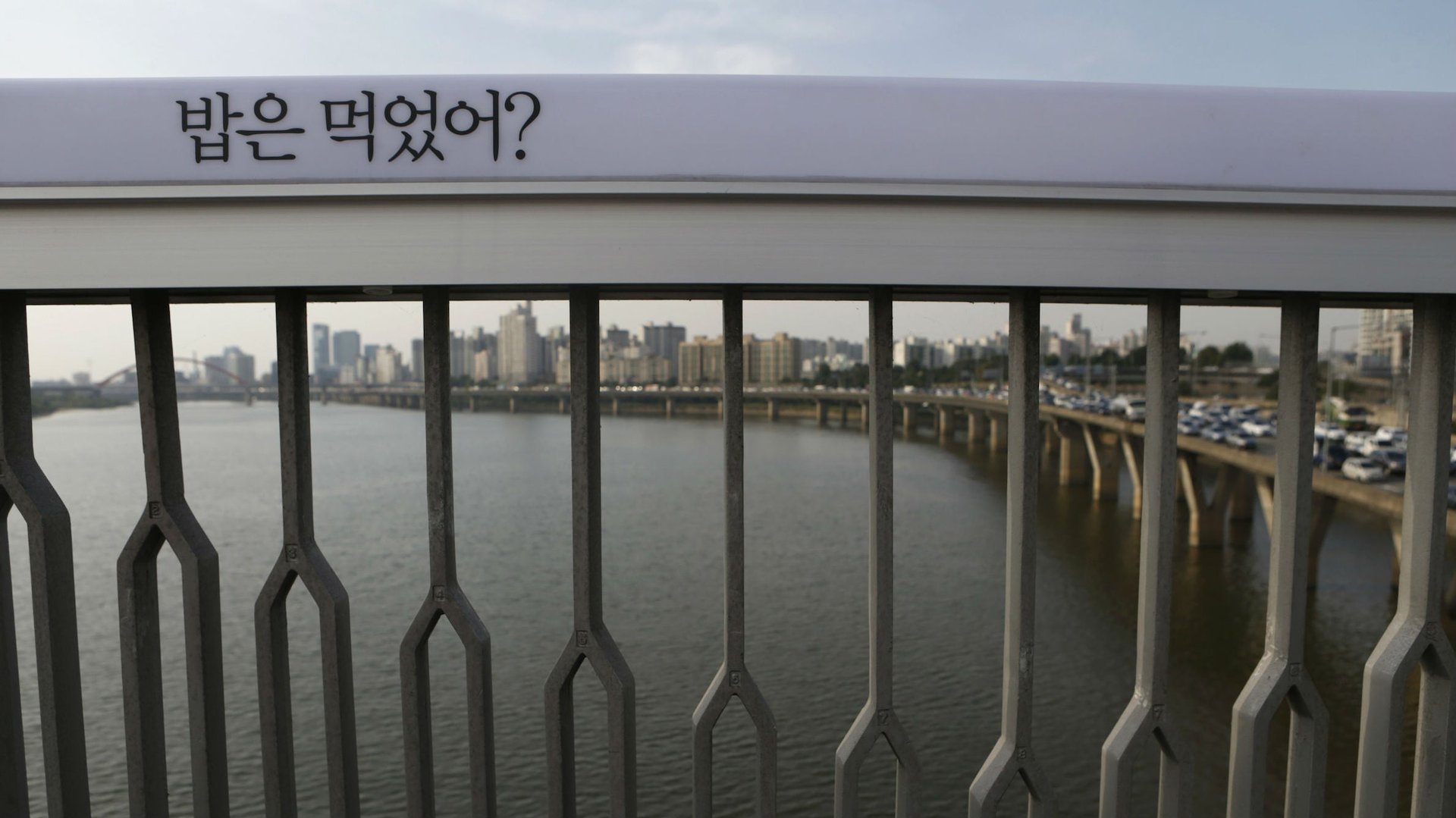

Still, that’s the highest rate of any developed country and more than twice that of the US or the average of the 34 OECD countries. What’s more, a new report this week from the OECD paints a bleaker picture. Over the past two decades South Korea’s suicide rate, while experiencing occasional dips, has trended upwards. Meanwhile, most developed countries are seeing their rates fall.

Fitting in with the traditional theory that suicides increase during hard economic times, suicides in South Korea—as well as Japan—increased in the mid and late 1990s, around the same time as the Asian financial crisis. But while these deaths leveled off in Japan at the turn of the century, Korea’s rate rose even as its economy recovered. It’s now Asia’s third largest economy, but suicides are costing the country as much as 4.9 trillion won (paywall) or $4.6 billion a year, according to the ministry of health.

What’s the problem? Some academics blame the country’s growing wealth inequality; a welfare system that’s left an expanding population of elderly people (among whom suicide rates are three to four times as high as the national average) with few savings; the notoriously competitive education system; or Korea’s culture of heavy drinking. Seeking help for mental health still carries a heavy social stigma—one reason why Korea’s consumption of anti-depressants was the lowest among OECD countries in 2011.

Another problem is that suicide has been a subject of fascination and sensationalism over the past several years. Korean media breathlessly reported the 2008 and 2009 suicides of a popular actress, Choi Jin-sil, as well as former president Roh Moo-Hyun. There were 1,700 suicides in the month following Choi’s suicide, 700 more than in a normal month, officials said. Researchers say graphic images and descriptions of the deaths, more prevalent in Asian media than elsewhere, contribute to a kind of glorification of suicide.

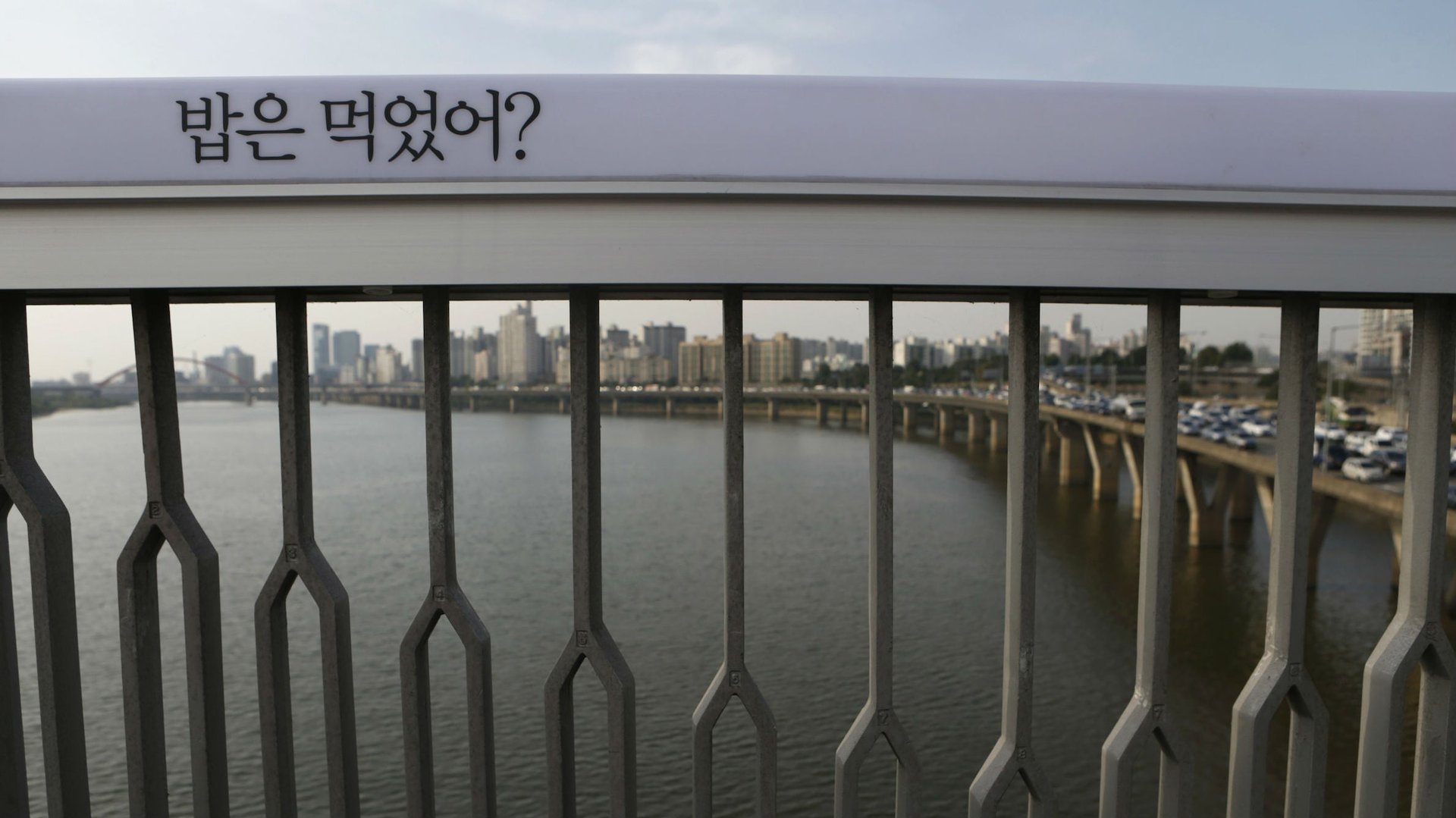

That’s slowly changing. South Korea has issued national guidelines to media. Troubled residents can call a 24-hour suicide hotline. Authorities also banned the sale of a lethal pesticide used for almost a quarter of all suicides between 2006 and 2010. Last year, signs were installed along a bridge in Seoul, where many have jumped to their death, carrying messages like “The best part of your life is yet to come.” Hopefully more South Koreans will start to believe that soon.