Polyamory is a quietly revolutionary political movement

Polyamory is no longer unusual. In areas of Brooklyn dominated by corporate-sponsored graffiti and homogenous warehouses-turned-craft-cocktail-bars, the practice of dating multiple lovers has developed into a social scene. There are regular sex parties, some listed on kink websites so attendees can add them to their Google calendars well in advance, others advertised only by word of mouth. And there are events where polyamorists get together and no one has sex: Film screenings, picnics, cocktail parties, and other PG-friendly rendezvous.

Polyamory is no longer unusual. In areas of Brooklyn dominated by corporate-sponsored graffiti and homogenous warehouses-turned-craft-cocktail-bars, the practice of dating multiple lovers has developed into a social scene. There are regular sex parties, some listed on kink websites so attendees can add them to their Google calendars well in advance, others advertised only by word of mouth. And there are events where polyamorists get together and no one has sex: Film screenings, picnics, cocktail parties, and other PG-friendly rendezvous.

“Tableaux” is one of these, a once-a-month, evening-drinks meetup at Lot 45 in Brooklyn, organized through Facebook. Attendees can choose to sketch drawings of posed models, but most people opt to stand around, mingling and talking. At the April 2018 meetup, a bearded, 20-something entrepreneur in a blue button-up tells me he’s a regular. “I love being at an event where I’ve slept with five people in the room,” he says. “It makes me feel proud.”

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Americans who rejected monogamy typically did so in an effort to throw off mainstream, normative culture and politics. But the attendees of Tableaux fit in with the rest of privileged, gentrified Brooklyn: They match the dark, tattered-glamor aesthetic of the room; wear dark-grey clothes and plenty of eyeliner; and are overwhelmingly white. In a group of more than 50, fewer than five are people of color. And, though people at the party tell me the polyamory community is ahead of the curve on gender politics, most present as cis; most queer women as femme. Sex is no more prominent here than at any other party in middle-class Brooklyn. We discuss vegan burgers and holiday destinations. Gin and tonics appear and disappear rapidly, and the abundance of iPhones and fast fashion suggests polyamorists have no problem with consumerism.

Yet many polyamorists consider the whole lifestyle to be radically transformative by virtue of its nature. Weeks before I went to Tableaux, I had coffee in Manhattan with Leon Feingold, an exceptionally tall, friendly polyamorist, eager to talk about his high IQ and his sexual philosophies. Feingold, who wore a red Hawaiian shirt and two necklaces, one featuring a Chinese star with flamed tips (designed at Burning Man in commemoration of his late wife) and the other pukka shells, said that polyamorists emphasize the importance of emotional openness and strong communication. When I asked him to be more specific about the values of polyamory, he told me the community embraces sex positivity and celebrates the full gender spectrum.

Feingold, who works as a real-estate broker and helped to establish a sex-positive, three-story, 15-bedroom apartment building in the Bushwick neighborhood of Brooklyn, believes polyamory reflects high intelligence. He told me it was illogical for me not to be polyamorous. “Why depend on just one person for all your needs?” he asked.

Polyamory is defined, very broadly, as “ethical non-monogamy:” Essentially, anyone who dates multiple people at once, where all partners know and are comfortable with this. Beyond that, the details vary. In the 1990s, when swinging was more popular, there were internet-forum debates that attempted to distinguish sex-focused swinging from relationship-oriented polyamory, but today plenty of people ignore this differentiation. Couples who are in open relationships—meaning they view each other as their primary partner but have sex with or date other people—are considered polyamorous. So too are those who refuse to have any one primary partner, but are in “non-hierarchical relationships,” meaning they view all their partners as equally important. A “triad” is a non-hierarchical relationship where all three people date each other, with equal commitments all around.

It’s difficult to know exactly how many polyamorists there are in the US. Elisabeth Sheff, an academic who researches polyamory and has written several books on the subject, says she tried to get a question about polyamory on the 2016 General Social Survey, a University of Chicago-based initiative that conducts annual nationwide surveys on social trends across the US, but the researchers in charge refused, saying that the sample would be too small for any meaningful analysis.

This, though, assumes rather than establishes that polyamory is a tiny minority. What research there is suggests otherwise: a survey of some 8,700 US single adults in 2017 found that more than one in five engaged in consensual non-monogamy at some point in their lives, while in a 2014 survey 4%-5% of Americans reported currently being polyamorous.

Sheff notes that measuring identity is complex, and further sampling is needed to get a definite understanding of the frequency of polyamory across the US. But, at minimum, these surveys suggest that the number of polyamorous Americans is in the hundreds of thousands, and perhaps in the millions. Certainly, interest has ballooned from the 1960s, when polyamory was taboo.

“In the ‘60’s there were very few explicitly sex positive communities. They were underground, hard to find,” says John Ullman, a 75-year-old living in Seattle, via email. “Personal ads for swingers or proto-poly people began to appear in the Berkeley Barb, the Seattle Helix, and other underground newspapers. People had to court potential partners and it was a risk to talk about being poly.” Today, there are countless online groups and meetups, as well as polyamory events organized around specific activities and interests, such as hiking, gaming, and science fiction.

There are now some places in the US where polyamory has moved well into the mainstream. Sheff says there are neighborhoods in Seattle where more and more polyamorists groups moved to be close to each other, and several polyamorists say they consider Washington state to be polyamory-friendly. Melissa Hall, an attorney in Seattle, tells me she knows her daughter won’t be the only child of polyamorous parents when she starts school. “There is a poly meetup almost every night in the Seattle/Puget Sound area, and most other large urban areas,” writes Ullman. “Today I see people asking why there isn’t a poly group in Gresham, Oregon, or Richland, Washington, instead of why isn’t there a poly group in the Northwest.”

The lack of overt political activism in today’s polyamorous communities is quite different from earlier generations of American polyamorists. The few who openly practiced polyamory in the 1960s and 1970s typically lived on communes, and outwardly rejected capitalist ideals of a nine-to-five, conventional lifestyle. Many practiced some form of communism, pooling all their resources together and sharing everything, from food to sleeping partners. In some cases, this commitment to “equality” went so far as to undermine free choice. One famous polyamorous commune, Kerista, based in San Francisco from the 1970s to 1990s, insisted that members live according to a strict sex schedule, rotating who they slept with each night within formally organized groups, or “best-friend identity clusters” of four to 15 people.

“What’s happening now is so much more healthy, because it’s deciding for yourself,” says Jessica*, a 34-year-old who asked to use a pseudonym as she’s not yet out as polyamorous to her parents. Jessica, who has a wide smile and the slightly scruffy look of a Brooklyn resident too distractedly happy to worry about preening, describes polyamorous politics as a mixture of socialism—a respect for a non-hierarchical society that values collective, community decision-making—and a libertarian belief that everyone should be free to make their own decisions without government interference. For example, Jessica and other polyamorists I speak with say there’s very little discussion about the right for polyamorous marriage, because few in today’s poly community believe government recognition of a union is a worthwhile goal.

However, while they may not be organizing as a collective around specific issues, many polyamorists today believe the act of dating multiple people is inherently political, since monogamy, they note, is inextricably linked with both economics and politics.

In the late 1960s, feminists made the groundbreaking argument that the personal is political: How we interact in private, and in our intimate relationships, has political implications, and therefore the tenor of those interactions should be examined in the public sphere. The way a husband treats his wife, for example, does not just characterize one individual relationship, but reflects widespread societal norms that determine both male and female career opportunities and expectations at home. Feminists, then, must bring a political lens to their personal relationships, and publicly examine the power structures that influence those private decisions. The people we choose to have sex with, and how we treat our romantic partners, are not just personal choices, but political acts.

Polyamory is radical politics from that perspective. Today’s polyamorists may not be rejecting conventional jobs or bourgeois consumption, but they are shifting fundamental structures of society simply by relating to each other differently.

Perhaps contemporary polyamorists’ embracement of and engagement with mainstream life allows them to surreptitiously change what it means to be “normal.” Progressive changes to gender roles, economic opportunities, and the definition of family, follow as consequences. For example, instead of one person (usually the woman) taking on the housework and the other (usually the man) doing paid labor all day, as in a traditional monogamous economic structure, multiple people living together in a polyamorous relationship can choose to work part time and still have the resources to live comfortably. If you’re okay with multiple roommates, even the most expensive neighborhoods become far more affordable.

Jessica, like many living in Brooklyn, could not afford her apartment on her income alone. Monogamists benefit from the financial advantages of being in a relationship, but they don’t have the same freedom as Jessica: They have to keep their one partner if they want to maintain their lifestyle. Polyamorists, though, are able to split the rent while still dating freely.

Often, polyamorists can pool their resources among many. Rather than being locked into a relationship to fund their apartment, they have the freedom to live with various partners, or move from one to another. Chaele, another Brooklyn resident who I first met at Tableaux and who asks to be only identified for her first name, recounts the story of a polyamorous friend who recently lost her housing soon after becoming pregnant, but was able to live comfortably with friends and lovers for several months before finding a new place of her own.

Polyamory also shifts the sexist narrative around sex itself. “At a really deep level, even though I hope we’re moving beyond this in some way, there’s still the idea that dating is like work for women and recreation for men,” Moira Weigel, who’s written a book on the history of dating, previously told Quartz. “Sex is a kind of work women do to get attention or affection, and men are the ones who have that to give.” The pervasive stereotype is that women are more eager for long-term monogamous relationships than men, and so, men pursue women for casual sex, while women seek a partner. In contrast, those I spoke to in the polyamory dating scene said both men and women are expected to enjoy sex for its own sake, without judgement, and that the “ghosting” and callous behavior so widespread in monogamous dating is practically unheard of in the polyamorous world.

Polyamory also has the power to transform traditional heterosexual family dynamics, and dismantle the gender norms demanded by that family structure.

Elise* is 14 years old and lives in Springfield, Virginia, not too far south of Washington, DC, with her mom, her mother’s boyfriend, and her mother’s boyfriend’s wife. There’s also her half-sister, two step-brothers, a roommate, and large dog in the house, as well as a “cave” room where the adults’ various partners occasionally stay the night. To Elise (who asked to be identified by a pseudonym), the most remarkable thing about her home is the pool.

“When I was in preschool, I came home one day and was like, ‘Mom, did you know that some people stop dating after they get married?’” Elise tells me when I visit her home in March. She’s naturally upbeat, wearing a blue t-shirt emblazoned with flying cats, and highlighter-pink hair held back with a bandana. She switches easily between the quintessentially teenage modes of self-deprecation and flippancy, the latter of which she applies to the many adults in the house: “Do you know how much money I can mooch off these people?” she asks me wryly.

The house is large, with sleek hardwood flooring, a dining room that easily seats 12, and a modern kitchen. The family knows combining parenting with polyamory is controversial but laughs at the suggestion that there’s anything unhealthy about their arrangement. “Our joke is always ‘won’t somebody think about the children?’” says Elise’s mother, Jill. “People say that all the time to disparage non-traditional relationships. But our kids have this house full of folks who are interested and engaged with them.”

Neither Jill nor her boyfriend Eric’s wife, Tamara Pincus, attempt to fulfill a parenting role to each other’s children; they treat them as they would the children of any friend, having amiable conversations but never offering discipline or motherly guidance. Jill, Eric (both of whom asked to be identified by first name only), and Tamara all have several other partners outside the house and a wide circle of polyamorous friends. Tamara works as a therapist specializing in polyamorous relationships, and runs a regular meeting group for polyamorists living nearby. Between 15 and 30 people from Springfield and the surrounding neighborhoods come each time, she says, and the conversations are focused on personal matters—how to deal with jealousy among participants in polyamorous relationships, for example—rather than broader political visions or activism.

“I don’t feel like our particular household is on some great political journey,” says Jill. If anything, “it’s a survival strategy.” Together, they can support each other and afford to live in a large, detached house with marble kitchen countertops and glossy wooden floors. “A lot of people are struggling financially,” she says. “A lot of people are lonely. This can really help people support each other.”

There are still sexist hang ups within polyamory. Though men and women are equally encouraged to enjoy sex, certain expectations differ widely; nearly every polyamorous woman I met identified as queer, whereas the men were mainly straight. And polyamory is certainly not a perfect preventative of societal sexism; I met several polyamorous men who mansplained or talked over their women partners.

Then there are the insincere polyamorists, typically men, who pressure their partners into polyamory simply because they’re interested in sleeping with others. These relationships are often identifiable by “one-penis policies,” meaning that both members of a heterosexual partnership are only allowed to date women. Such policies are looked down on by the polyamorous community and considered a sign that someone hasn’t embraced a truly free and emotionally open approach to polyamory.

Polyamory also struggles with racial diversity. There are growing numbers of regional and national polyamory groups and events in the US, such as Poly Dallas and Black & Poly, with predominantly black attendees. And Feingold, the Brooklyn landlord, presents polyamory as widely diverse both in terms of race and class. “You meet millionaires and people on food stamps,” he told me. Later, by email, he added that Open Love NY, the community he founded, “has worked over the last decade to improve intersectionality, diversity, and awareness, and has actively and intentionally increased representation of and input from underprivileged populations within our community.”

Michael Rios has been a prominent member of the polyamorous community since the 1960s, and doesn’t consider racial diversity an issue. “There’s no problem,” he says. “If you said, ‘Find me 50 people of color who are polyamorous,’ I’d say sure, give me an hour.” He adds that “neurological diversity”—welcoming those with ADHD, autism, or Tourette’s, for example—is far more of an issue. “Most of our conflict problems aren’t because of race. That’s an artificial one,” he insists. “If you have a partner who has Asperger’s, you’ve got some learning to do and they’ve got some learning to do. I’ve had lovers of color and it didn’t frankly come up in any way shape or form.”

But many polyamorists say the community is still predominantly middle-class and white, and there remains a distinct lack of events that are racially diverse. Kevin Patterson recently published a book, Love’s Not Color Blind, on how the polyamory community needs to address its white hegemony

Chaele tells me the racial prejudice that exists in polyamorous communities reflects the wider world. “We don’t live in a vacuum utopia,” she says. “White people get centered in everything.” The major polyamory groups are predominantly white, she says, and there are smaller offshoots for those who feel uncomfortable identifying as a minority. Though Chaele is involved in majority-white polyamory groups, she says she occasionally wants to surround herself with other African American polyamorists. “It’s very hard to trust and want to be in predominantly white spaces sometimes,” she says.

The majority-white demographics can be perpetuated by attitudes towards race within the community. Just as elsewhere in dating, Chaele says, black people experience both polyamorists who aren’t interested in them because of their race, and others who fetishize it. One woman at Tableaux told me there’s a strong overlap between the polyamorous and kink communities, and that she gets lots of requests for racist sex play. “Either some kind of slavery thing or white people being owned by a slave,” she says. “It’s a gross thing that I don’t get down with, but am asked about all the time.”

There are various theories about the cause of polyamory’s racial divide. Some of those I interviewed suggest it’s far easier to be polyamorous if you’re white and wealthy. Those already marginalized and persecuted due to their race or economic standing would understandably be less likely to take part in a relationship that’s viewed as transgressive. Others believe it’s because the polyamory community in the US was largely built by white founders, who reached out to others like them and didn’t try to be more inclusive.

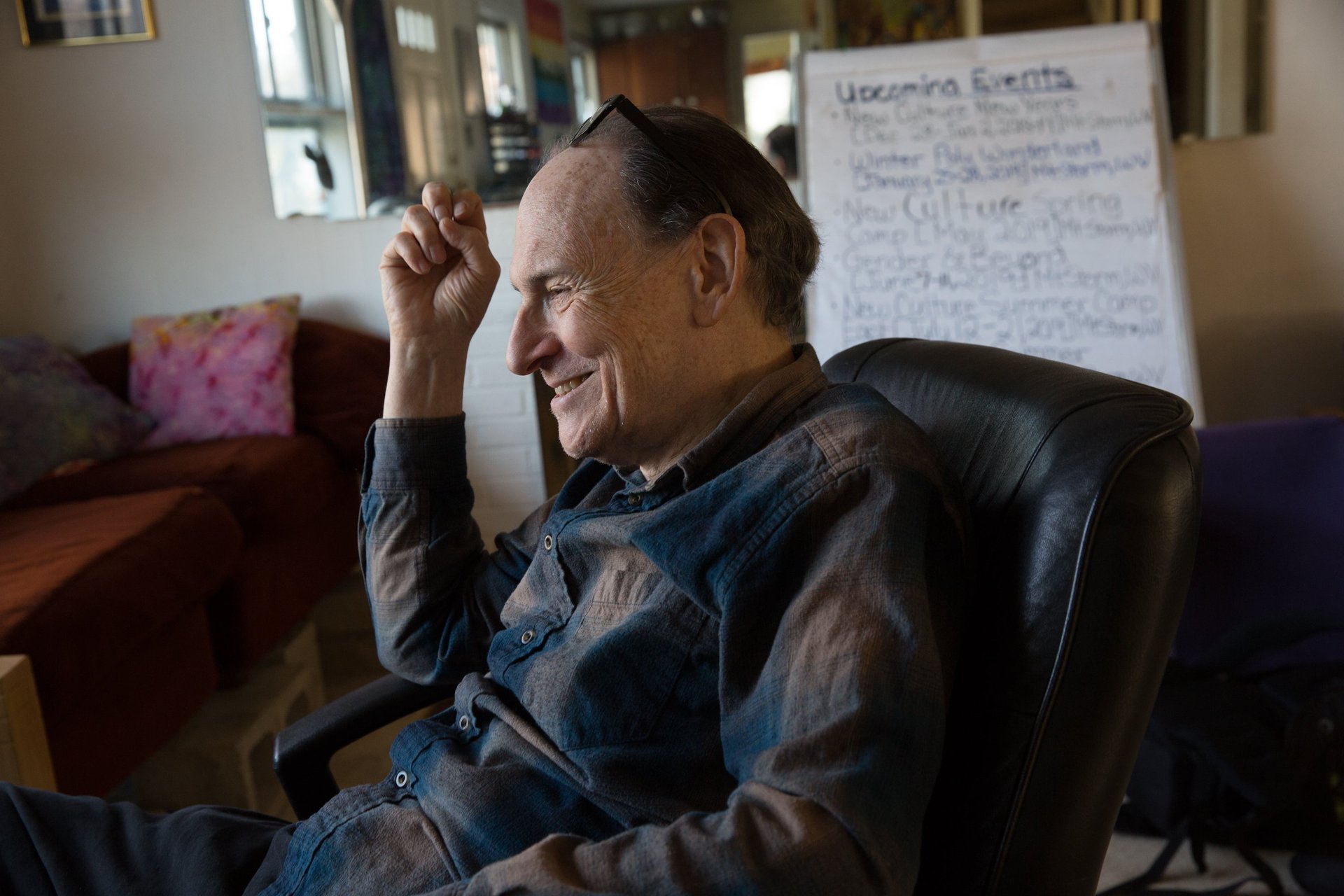

Rios, now 70, is one of those early founders. He helped run a polyamorous commune that moved throughout DC, Maryland, and Pennsylvania in the 1960s and 1970s, and today leads a co-living space in Arlington, Virginia, predominantly filled with polyamorous people. He’s tanned and sinewy, with a tendency to lean forward slightly and touch people on the shoulder as he talks to them. He originally wanted to be a Roman Catholic priest, but later decided that polyamory was a better fit. “If you’re Christian you’re supposed to love everybody,” Rios says. “How does monogamy fit into that?”

The polyamorous commune Rios helped form in the 1960s lasted for several decades before winding down in the early 1990s after members drifted away. He continued to believe in communal living, though, and in 2001 founded his current polyamory-friendly community. He’s running things a bit differently this time. For example, in his current co-living space, members aren’t forced to share their assets, and everyone can have their own private possessions. In fact, the community—called “Chrysalis”—resides in two houses next door to each other, both owned by Rios; all residents pay him rent. There are usually about 10 community members at any time, and they are free to earn money and accumulate their own private wealth, and to come and go as they please.

Some polyamorists outside the community say the hierarchical structure seems antithetical to polyamorous principles, but Chrysalis residents present their home life as idyllic. When I visit at the end of March 2018, the house is warm and slightly messy, like the lovingly disheveled home of college students. In my afternoon there, I rarely see two people talking without also stroking each other, or kissing, or sharing a lingering hug.

Rios says polyamorists today are far less politically zealous than in his younger years. “When I started off, anyone who was polyamorous was making a radical social statement,” he says. “These days, you get a lot of people who are in it because they want a more open sexuality. These people are not necessarily liberal, or feminist, or anything.” Many do, however, care about diversity.

When I visited, the house was majority white (five Caucasian and three Jewish), though one resident is African American, one South Asian, and one Latinx. Several younger members told me they’d like their community to become more diverse, and Rios later mentions in an email he’s planning to host an event organized by people of color. Chrysalis was once entirely made up of those in their 40s and older, but has been steadily getting younger since September 2016. That’s when Indigo Dawn, now 27, became the first 20-something to join. Two other current members in their 20s said they came to Chrysalis in part because they were attracted, both romantically and sexually to Indigo. In total, there are now four 20-somethings living full time in Chrysalis, and two who spend around half their time there.

Indigo, who identifies as a “non-binary demigirl” (meaning someone who partially, but not wholly, identifies as female, and prefers to use the pronoun “they”), is a simultaneously disconcerting and captivating presence. When they’re not talking, their blue eyes have a vacant, glassy look and their face is utterly blank, almost as though they’re switched off. They seem wary when I ask for an interview. But, after each question I ask, Indigo pauses, smiles, breathes deeply as though in serene meditation, and then speaks with great emotion and intensity.

“I think I’m changing the world,” says Indigo. “I’m creating long- and short-term community in which people can know their truest selves, and can get closer and closer to that core of self.” As Indigo talks, their gestures are like dance moves; they circle their hands over each other as they say “closer and closer,” miming the meaning.

Before joining Chrysalis, Indigo worked at Teach for America in Atlanta, and was in a monogamous relationship. “I had this emptiness. I thought, ‘Is this all life is?’ It isn’t enough,” they say. Chrysalis gave Indigo purpose.

Rios and his partner Sarah Taub have been running the Center For a New Culture (CFNC), a non-profit focused on teaching people the skills to create more intimate, loving relationships, since 2004. Today, Indigo and others in Chrysalis develop polyamory-friendly “New Culture” events in Virginia that are open to the wider public, such as evening workshops on personal growth and how to have drama-free relationships, and several-day-long sessions called “New Culture Camps.” For example, one three-day event, Winter Poly Wonderland, is described as “not just a party, or a conference” and offers workshops on intimacy building and relationship skills, as well as “hugs and cuddle piles” and dance sessions.

“New Culture is our baby,” says Indigo, bringing their hands together to form a cup and gazing at the invisible “baby” resting there. There are now also formal or informal New Culture groups in Oregon, Hawaii, North Carolina, California, Washington state, and Canada.

Indigo says they are in a “deep, long-term, loving, sexual relationship” with another Chrysalis resident, Dawson. They add that their other relationships within the house are intimate, but not necessarily sexual. (Ahead of our talk, Indigo and another housemate were lying on a bed, cuddling and kissing.) Indigo believes the culture of acceptance within their polyamory community is innately transformative, and describes the community’s philosophy as one of “abundance and freedom.” “It shows people you don’t have to hide your needs,” they say. “You don’t have to limit yourself to be so small that you’re just a cog in the broader system.”

The values of abundance and freedom, though, can come into conflict. To be free, after all, you have to be free to reject people and experiences you don’t want. This means that you can’t have sex with everyone, love everyone, or express yourself emotionally to anyone you want: If they don’t want to hug or talk to you then, polyamorists believe that the only right way to respond is with acceptance. Those who have been polyamorous a long time know the practice isn’t simply about love and sex, but independence and autonomy.

In this way, polyamory can encourage greater independence than traditional monogamous relationships. “I’m working towards having a completely loving relationship with myself,” Houston Ward, another Chrysalis housemate, tells me. “My true companion in life is myself.”

Cultivating this approach can be extremely challenging. Sarah Taub, Rios’s longtime partner, has long, grey hair, and her attitude suggests a time-tested tolerance for the many unsatisfactory and irritating details of being alive. She’s 50 years old, has been with Rios now for 17 years, and has weathered various stages in their relationship. When another of Rios’s partners, Jonica, moved in, for example, Rios pulled away from Taub. For five years, Taub struggled to accept the change. It was, “a painful period,” she tells me.

But Taub excuses Rios for drifting away, acknowledging that she often snapped at him in the period before he met Jonica. “That can be super hard for anyone,” she says. She learned to meditate and appreciate being by herself. And she bears no ill will towards Rios; after all, she has also dated people who wanted to be with her more than she wanted to be with them. After five years, Taub says she eventually she came to appreciate Jonica’s presence in the house, and to feel happier.

Taub points out that polyamory within the broader US culture is going through a process similar to Chrysalis’s adjustments as it grew. “The people who were initially into polyamory were really amazing, interesting, weird, iconoclastic—willing to go against all cultural norms for reasons both healthy and unhealthy,” she says. There can be something of a “culture clash,” she says, between those who were polyamorous back when it was more transgressive, and the younger, more mainstream polyamorists who are making the movement their own, seeking to improve it where they see fit, and gradually embracing more and more people and perspectives. These dynamics and politics are typical of any large movement. “First there are the pioneers and then there are the settlers,” says Taub. “We’re in the settler phase now.”

Chrysalis is that rare community that combines both pioneers and settlers under one roof. For the most part, polyamorists are more likely to group together based on demographics, finding compatriots in, for example, suburban Virginia, progressive Seattle neighborhoods, and trendy Brooklyn bars. They’ve gone from oddity to humdrum normality and, though the community has largely abandoned some of the overt political ideals of polyamorous pioneers, polyamory’s new settlers are still, subtly but perceptibly, creating change. Polyamory today is not an overtly political movement. But it is still radical—quietly, personally, and apolitically.

This story has been updated with additional comments from Leon Feingold clarifying his position on diversity in the polyamorous community.