What’s a moon rock worth, anyway?

In a November auction, an anonymous buyer purchased approximately 0.2 grams of soil from the surface of the moon for $855,000.

In a November auction, an anonymous buyer purchased approximately 0.2 grams of soil from the surface of the moon for $855,000.

At $4.28 million per gram, the lunar regolith carries a higher price than any mineral on earth, despite it likely being composed of such commonplace elements as oxygen, iron, silica and calcium.

Yet very few people expecting to do business on the moon are counting on bringing back moon rocks to sell here on earth at auction; they’ll bring it back for scientists to examine.

Does that mean the intrepid moon rock purchaser made a terrible investment, buying a commodity that is about to become much more prevalent? Not so, according to Cassandra Hatton, a vice president at Sotheby’s who organized the auction of space memorabilia that included the lunar samples.

“I think of the rocks that we sold as being parallel to say a first edition of a book,” Hatton told Quartz. “The first edition of Newton’s Principia is worth maybe $350,000. You can get a paperback translation of Newton’s Principia for maybe $20. The accessibility of those paperbacks has in no way diminished the value of the first edition.”

In other words, these rocks aren’t just valuable because of where they came from, but for why and when. Finding valuations for artifiacts like these isn’t easy—one of Hatton’s articles for Sotheby’s websites is called “When Science Becomes Art.”

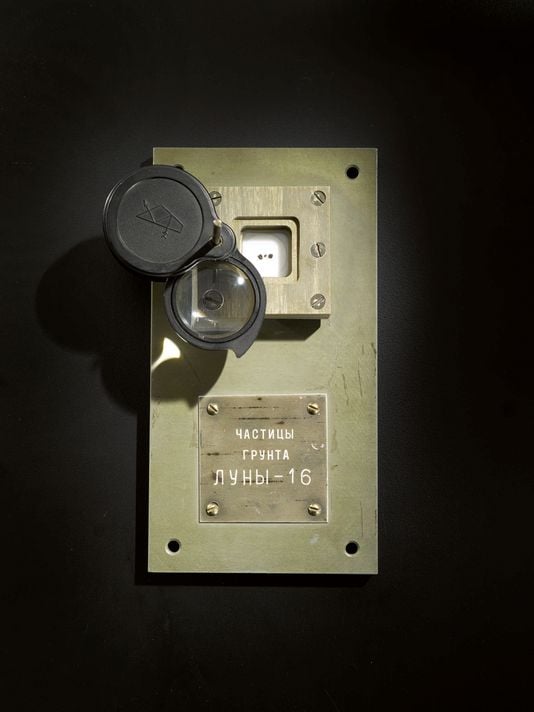

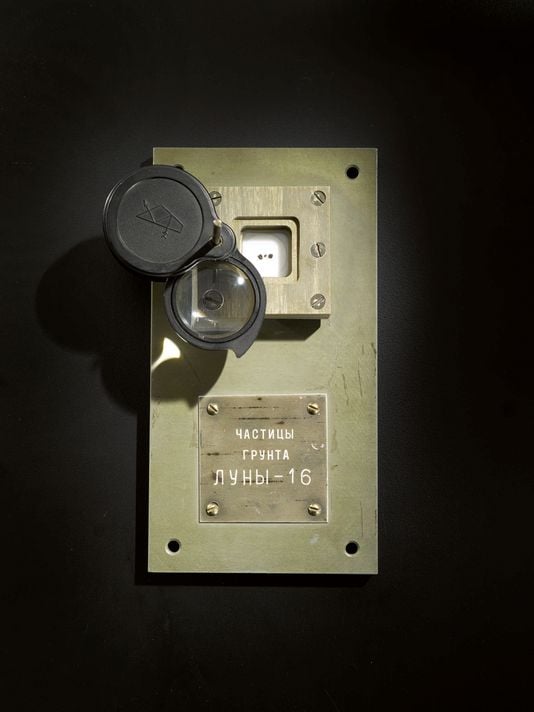

When it was time to set a starting price for the lunar sample sold last month, Hatton did have one advantage: Her auction house had conduced the only previous sale of a moon rock, this one, in 1993.

Following the end of the Cold War, Sotheby’s held an auction of artifacts related to Soviet space exploration. This sample was consigned to the auction house by Nina Koroleva, the widow of the former director of the Soviet space program, Sergei Korolev. Because it was given to Koroleva by the Soviet government, as far as Sotheby’s knows, it was the only human-returned moon rock that has ever legally come into private hands.

On earth, scientists estimate there are about 60 kilograms (132 lbs) of lunar rocks that arrived as meteorites, chipped off the moon by the impact of an asteroid or comet and flung to earth. Those rocks can be legally sold. But things are different with the samples returned by scientific missions to the moon.

The 382 kilograms (842 lbs.) of moon rocks returned to earth by astronauts during the Apollo program are all officially the property of the US government, and cannot be sold. That hasn’t stopped some of the rocks from slipping into private hands, because the US handed out samples as goodwill gifts to US state governors and foreign nations.

But the US still maintains legal claims on the rocks, and there are ongoing efforts to track them all down. Former NASA investigator turned life-long moon rock hunter Joseph Gutheinz said this year that all but two—New York’s and Delaware’s—of the fifty lunar samples given out to state governments have been identified; for example, in 2010, moon rocks gifted to Colorado were discovered in the home of an 88 year-old former governor.

The 135 samples doled out to foreign countries are proving harder to track. Malta’s was stolen, and Cyprus didn’t even receive its sample—apparently, it was pocketed by the son of a US diplomat. Two different samples given to Spain were kept by the families of the strong-men then ruling the country, Francisco Franco and then Luis Carrero Blanco.

The Soviets brought back 300 grams of lunar samples using robotic landers. Most are thought to be retained by the Russian government, with the exception of the Koroleva sample. When Sotheby’s first auctioned it off 26 years ago, it sold for $442,500, or about $2.2 million per gram.

That gave Hatton some place to start her 2018 appraisal of the sample, which the auction house predicted would sell for a price between $700,000 and $1 million.

There is another method to valuing moon rocks: A group of NASA interns stole a safe full of moon rocks from the US space agency in 2002. They were quickly caught, and in the course of their prosecution, the government established the cost of the theft by arguing that taxpayers ‘paid’ $50,800 per gram to obtain the samples during the Apollo program, a little over $300,000 in 2018 dollars.

Of course, US law would forbid anyone paying that price for the Apollo samples. That’s one reason why the recent Sotheby’s auction produced a higher value. In 2017, Hatton curated the $1.7 million sale of a lunar sample retrieval bag used by Neil Armstrong that wound up on the market, complete with some lunar dust still inside.

“The bag itself is valuable because it was a significant artifact from the Apollo 11 mission, and the presence of moon dust in the bag proved to us that it went to the moon,” she said. “Whereas the moon rocks that we just sold, the value primarily derived from the fact that they were taken from the moon—they are lunar material.”

But, she cautions, “you don’t know what some of these things are worth until you offer them at auction and see what buyers are willing to pay.”