Farewell my concubine: Mo Yan’s Nobel Prize heralds masculine wave in Chinese lit

Five years ago book agent Toby Eady was giving a talk in Beijing when an audience member asked him why he consistently promoted books about the female Chinese experience—chronicles of Chinese Cinderellas, concubines’ daughters and the like. Was Eady promoting a one-sided picture of victimization to Western eyes, asked the audience member. What about the male side of the Chinese story?

Five years ago book agent Toby Eady was giving a talk in Beijing when an audience member asked him why he consistently promoted books about the female Chinese experience—chronicles of Chinese Cinderellas, concubines’ daughters and the like. Was Eady promoting a one-sided picture of victimization to Western eyes, asked the audience member. What about the male side of the Chinese story?

Eady, who nursemaided best-sellers like Jung Chang’s “Wild Swans”–dubbed China’s “Gone with the Wind,” paused a beat before retorting, “Do you know who belongs to book clubs? Women.”

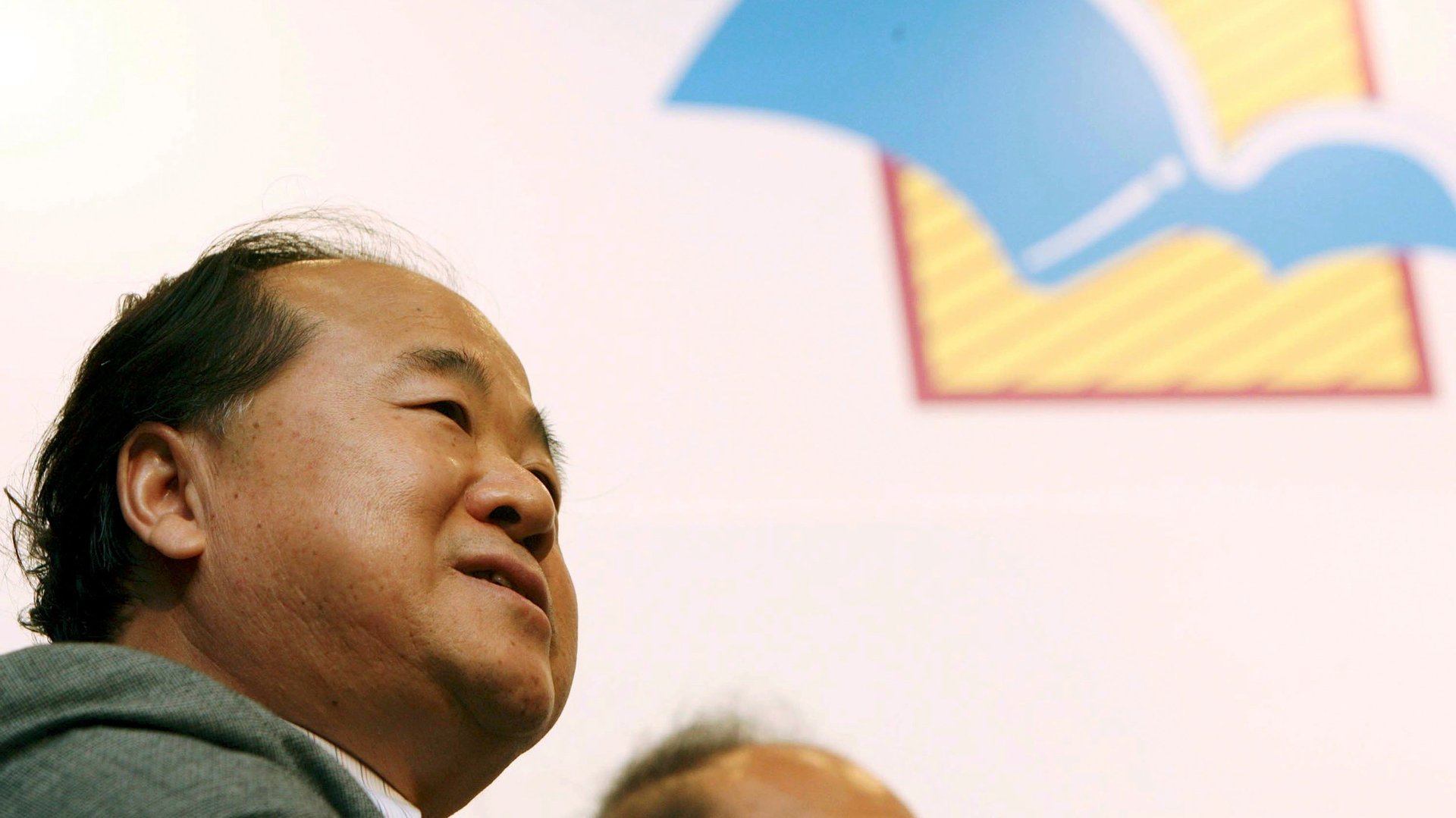

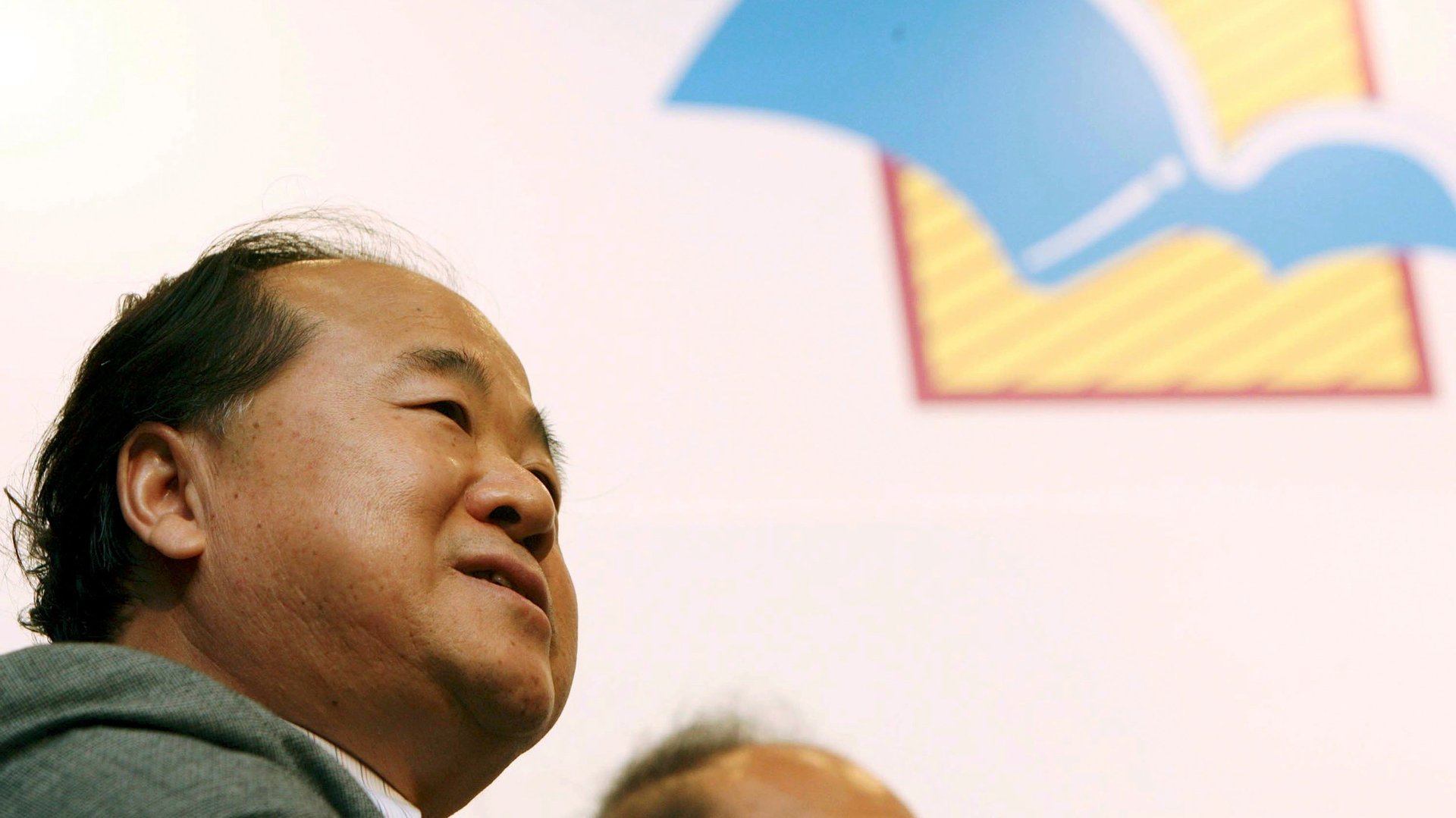

The awarding of this year’s Nobel Literature Prize to Chinese author Mo Yan marks a swing of the pendulum in how the West sees Chinese literature, highlighting the increasing number of male Chinese writers reaching a global audience.

Male Chinese writers might not be as famous as female ones, but they present the other, much-needed perspective–one that is lustier, masculine-minded and befitting a nation facing a male surplus.

To understand the significance of the masculine swing, imagine if the outside world’s perception of, say, America, were shaped primarily by reading writers like Edith Wharton, Emily Dickinson, Toni Morrison, and Betty Friedan. No Hemingway, no F. Scott Fitzgerald, no Louis L’Amour, no Raymond Chandler. What a strange America this would be.

Mo Yan and his cohorts write salacious stories. Graphic. Scatological. The obsessions are making money, having sex, with possessing rather than being possessed.

Take this passage from Mo Yan’s Red Sorghum, a full throttle yarn about a family’s struggles during the Japanese invasion. Granddad Yu is heartbroken after grandson Douguan’s testicle is bitten off by one of the packs of dogs made feral by starvation. Douguan’s childhood friend Beauty is encouraged to indulge in some sex play to see whether his parts are in working order:

“Timidly, she held it in her sweaty hand and felt it gradually get warmer and thicker. It began to throb, just like her heart.”

Granddad, elated to see a continuation of the family line, runs out, uttering perhaps the most memorable line in the book: “Single stalk garlic is the hottest!”

These stories offer another perspective on Chinese obsessions—in this case, family lineage. (Anyone wondering whether this lineage business is just highly colored fiction need only scan last week’s news about Hong Kong billionaire Cecil Chao, who put out $65 million to a successful suitor for his lesbian daughter’s hand. Talk about Matrimony on A Bounty.)

There is, of course, more to male Chinese writing than Rabelaisian humor and power-crazed protagonists. A particular favorite of mine is the Inspector Chen series, written by Anthony Award winner Qiu Xialong. The books detail the adventures of Shanghai poet-policeman Chen Cao and are set in the early 1990s, when China is beginning its rapid economic climb.

These are gentle stories, filled with melancholy and mouth-wateringly good descriptions of food. Endemic government corruption means Chen rarely gets his man, even if he solves the case, and his peregrinations bring to mind Donna Leon’s Inspector Brunetti, or Alexander McCall Smith’s Precious Ramotswe.

For too long, Western perceptions of Chinese have been essentially a female one, brought about to a large extent by the hugely successful writings of writers ranging from Han Suyin to the two Amys, Tan and Chua, who, though American, draw hugely on their Chinese roots for their stories. They have offered vivid, touching, and loving portraits of dysfunctional families, of the immigrant experience, of female empowerment. Stories that need a woman’s touch.

In “The Good Women of China,” journalist Xinran Xue describes a visit to a remote part of China where women walk with a strange swagger. She discovers it is because the women live in a dry region with little forestation, and are forced to use sharp-edged leaves to staunch menstrual bleeding. I doubt a male writer would have spotted that telling detail.

Of course, these are stories that need to be told. But the surge of stories with tropes of infanticide, abortion and rape reinforce Western perceptions of the Chinese experience as being overwhelmingly feminine. As victims or objects of desire.

Women’s stories, no matter how vital, don’t necessarily square with all that’s going on in China today, which is facing a surplus of males following three decades of a government-mandated population planning policy—popularly referred to as the one-child policy– that reinforced Chinese families’ cultural preference for sons. By some estimates, there are now roughly about 120 men for every 100 women now, and the numbers are much more skewed in rural areas.

In 2009, I visited such a gender-imbalanced village in central China while reporting for the Wall Street Journal. Three of the village men had been the target of bridal scams. Due to female scarcity, bridal prices—like a male dowry and called cai li in Chinese—had shot up to as much as several years’ farming income. These men and their families had borrowed heavily to pay the bride prices, only to see the women decamp with the money.

The story had potential tragicomic overtones. I had visions of women sprinting across rice fields, veils rippling in the wind. Villages filled with horny, dejected men.

But the reality was a bit more grim, The village, called Xin ‘An, or New Peace, is mostly filled with old people and children. Few people can make a living farming the family plot, so the youth leave for city jobs. The few remaining men intend to marry only to dump their wives back in the village, as caretakers and bearers of children. However, many women—having tasted the delights of financial independence and city living—weren’t biting. I could see why. Xin’ An’s bucolic charms were few. The village had just one shop, and it sold things like detergent and fertilizer. No lipstick, no face cream.

New Peace Village was undergoing a subtle shift in its way of thinking. One of the duped grooms’ fathers worried about scraping together enough cai li for his other, still unmarried sons. “Wish I had daughters,” he said ruefully, upending centuries of ingrained teaching.

Mo is not the first Chinese author to get the Nobel nod. Gao Xingjian (currently a French national, but born in China) won in 2000 for his travelogue Soul Mountain, a far less accessible piece of work. Mo’s win is yet another small step that helps direct the world’s attention to the writings of Chinese men. Their kind of sinewy prose reflects the more aggressive aspirations of today’s China, increasingly intent on promoting its worldview and place in the world