The number of people without electricity fell below 1 billion for the first time ever in 2018

This year, in October, the International Energy Agency, an OECD intergovernmental organization that is one of the most influential think tanks in the energy-policy world, announced a striking finding: Global data gathered in 2017 show that the number of people without electricity fell below 1 billion for the first time ever.

This year, in October, the International Energy Agency, an OECD intergovernmental organization that is one of the most influential think tanks in the energy-policy world, announced a striking finding: Global data gathered in 2017 show that the number of people without electricity fell below 1 billion for the first time ever.

This is no small thing.

Almost certainly, you’ve had a time recently where you’ve been set back due to lack of electrification. Your wireless headphones ran out of juice on your train or bus ride home from work, perhaps, and you had to just stare silently at the back of the head of the person in the seat in front of you for 30 minutes. Or your phone died while you were out on a long bike ride, and you had to feel your way back home, ending up spending an hour on what should have taken you 20 minutes. But these are minuscule problems compared to those faced by people with no access to electricity whatsoever. Many of the basics of life that those in wealthier parts of the world take for granted are impossible without power.

There are some obvious advantages, like being able to refrigerate your food, and gaining access to communication networks. But there are likely massive downstream impacts that are less readily apparent.

Without electricity, your day is entirely determined by the rise and fall of the sun. That may seem idyllic to those beset by sleep-stealing screens, but for those without outlets, research suggests it’s a significant barrier to advancing economically and academically. One recent World Bank study, for example, found that lack of reliable electrification was costing Pakistan $4.5 billion a year (pdf) in gross domestic product. An academic study published in 2017 found that, in Cambodia, access to rural electrification (paywall) increased average household consumption (which the researchers took to suggest an increase in household income) and helped children stay in school for longer on average.

The latter finding accords with what economist Tim Squires discovered in 2015, when, as a PhD student at Brown University, he published a paper finding that expanded access to electricity in Honduras from 1992 to 2005 (pdf) led to significant increases in school attendance and educational attainment. The reasons why are intuitive, once you see them laid out in front of you: Imagine coming home from school at 3pm then having to do your chores before dinner. Half the year—and most of the school year—the sun will have set by the time the chores are done and you won’t be able to read your homework in the dark. Kerosene, candles, and batteries are too expensive, and cheap fuel sources like firewood, charcoal, manure, and other biomasses, emit air pollutants that can be extremely unhealthy.

That brings us to another huge problem exacerbated by lack of electrification: poor health. The World Health Organization puts it succinctly: “Unreliable electricity access leads to vaccine spoilage, interruptions in the use of essential medical and diagnostic devices, and lack of even the most basic lighting and communications for maternal delivery and emergency procedures.” In other worse, an electrified world is a healthier world.

Not every study has concurred with the belief that access to electricity will heal all that ails the poorest parts of the world. One recent, rigorous study of rural Kenya, for example, found that electrification did not have “meaningful medium-run impacts on economic, health, and educational outcomes.” However, at the same time, the study did admit that its data suggested “current efforts to increase residential electrification in rural Kenya may reduce social welfare,” which couldn’t hurt a country like Kenya, which is in the bottom 20% of overall GDP per capita in the world.

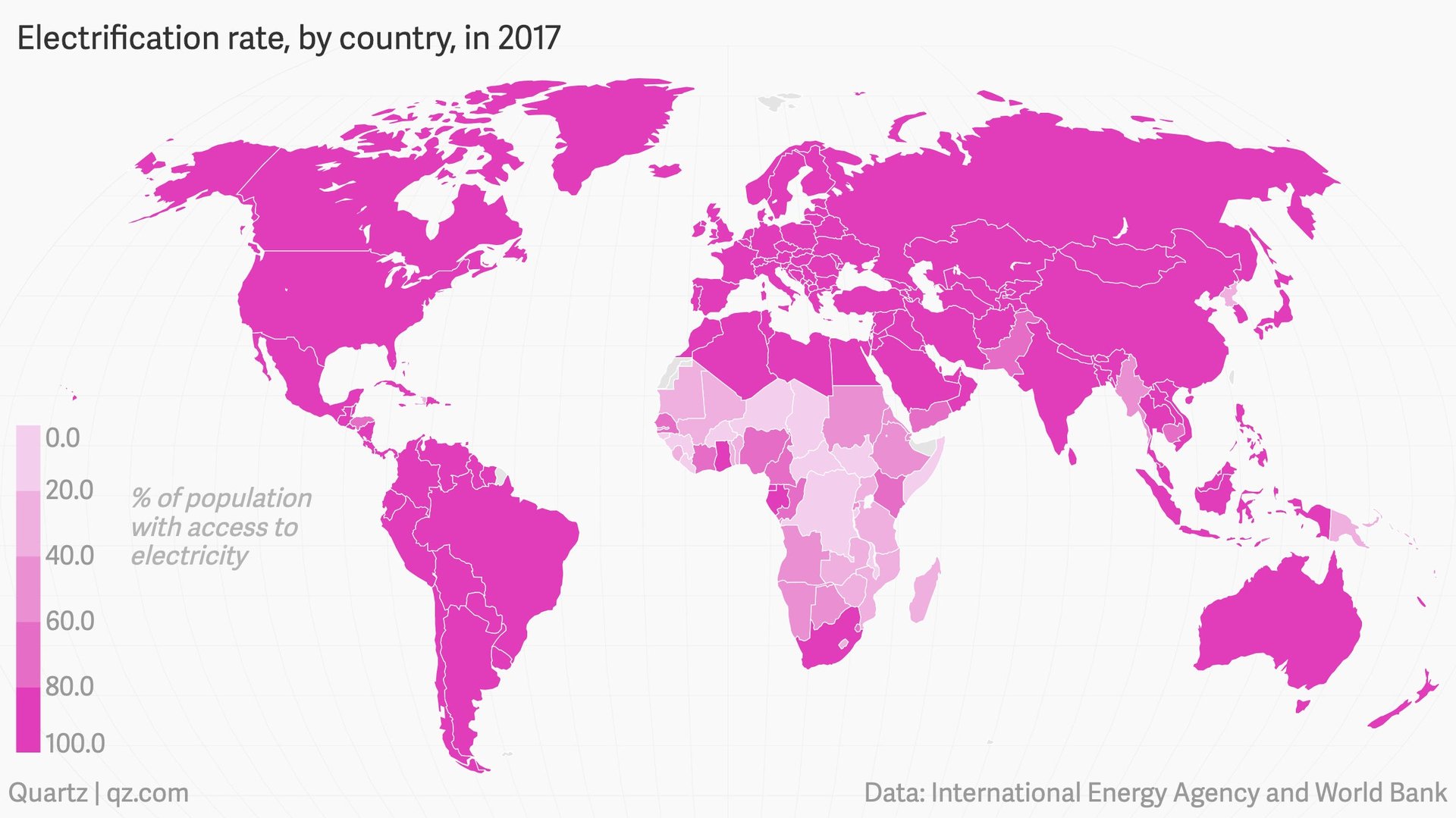

There were 7.55 billion people alive in 2017, and 87% of them had access to electricity. The remaining 1 billion people without electricity access tend to live in the poorest countries on the planet. According to the International Energy Agency, some 600,000 of them live in sub-Saharan Africa:

The good news is that, especially with the costs of renewable energy plummeting, it’s entirely possible to bring energy to nearly the entire world. There are dozens of examples over the last two decades to emulate. Laos and Nepal, for example, went from having nearly no electricity in the year 2000 to both being over 90% electrified in 2017. India and Indonesia, two of the world’s most populous countries, went from about 55% electrified in 2005 to 87% and 95%, respectively, in 2017. And it took Kenya just 10 years to raise the share of its population who had access to electricity from 18% in 2007 to 73% in 2017.