This is the most valuable real estate on the moon

Location, location, location. It’s the dogma for every real estate agent, and it’s equally true on the moon.

Location, location, location. It’s the dogma for every real estate agent, and it’s equally true on the moon.

The discovery of water on the moon—and how that could help humanity’s exploration of space—is what’s driving efforts to return to Earth’s satellite. But water isn’t everywhere on the moon; it’s only suspected to be in a few locations where concentrations are significant. And that could set up not just a scarcity problem, but the possibility for an innocent (or not so innocent) science experiment to trigger a colonial-style scramble for resources.

The best bet for big deposits of ice are the lunar poles, which receive less sunlight than the equatorial regions. There are deep craters that are never touched by the sun’s light at all, and remote sensing suggests that is where water is concentrated. The temperatures there are nearly -400 degrees F.

How will we get that water? Ivory tower lunar prospectors have tested heated drills in the Antarctic and developed passive extraction mechanisms based on thermal tents—heat the ice, capture the vapor, and you’re in business.

Naturally, these machines require power, and the most reliable power source in space is the sun, batteries being quite heavy and nuclear power quite complicated (both politically and when it comes to safety). But you might have guessed a “permanently shadowed region” doesn’t have a lot of sun, and that is where the Peaks of Eternal Light come in.

It’s quite convenient, really: Alongside some of these dark craters, there is high ground that is always in sight of the sun. They were first hypothesized and named in the 19th century by European astronomers as “montagnes de l’éternelle lumière.”

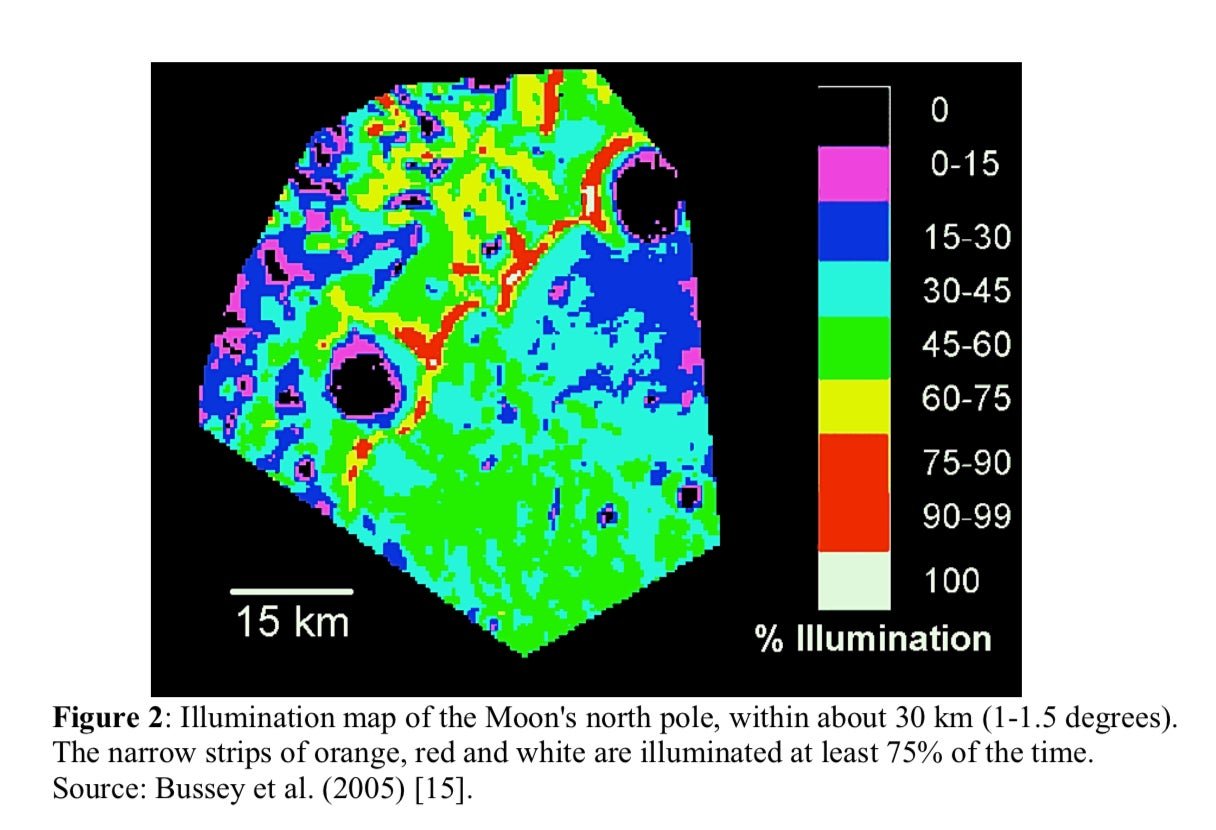

Recent sophisticated efforts to map the moon have established these peaks are quite real near the lunar north pole, and available at the south pole. A solar panel raised just 10 meters off the surface would collect the sun’s light more than 90% of the time. But there is not much of this land, effectively slivers of territory along ridges and crater rims.

The promise of a constant power source right next to a vital resource. What could be better? Actually, there is something that could be better: a legal regime that gave us any clarity about how this real estate can be occupied.

Space law is based on 20th century treaties that did not contemplate the growing ability of not just governments but also private corporations to act beyond the Earth. In particular, there is no mechanism by which anyone can claim property rights over an astronomical body or some sub-set of it, because they are for humanity writ large.

Potential space conflicts are addressed through the idea of non-interference: If someone is doing something on the moon (or elsewhere), another party can’t come mess with their activity. This idea allowed the US government to grant some rights to potential space miners in 2015. While they couldn’t claim land on the moon or an entire asteroid, a company that extracted a resource from one of those places could say they owned it.

Contemplating the intersection of scientific discovery, technological advancement, and legal conundrum, an astrophysicist, ethicist, and political scientist—Harvard-Smithsonian’s Martin Elvis, King’s College’s Tony Milligan, and the Missouri University of Science and Technology’s Alanna Krolikowskic—came to a startling conclusion in a 2016 paper:

“Effectively a single wire could co-opt one of the most valuable pieces of territory on the Moon into something approaching real-estate, giving the occupant a good deal of leverage even if their primary objective was not scientific enquiry.”

It works like this: There are legitimate scientific experiments to be conducted on energy the sun emits as radio waves longer than ten meters, which are difficult to detect on earth due to interference. But one of these thin ridges of permanent sunlight would be a perfect place to set up a long, skinny antenna to constantly monitor the sun’s long-wavelength emissions.

And due to the way we interpret space law, the presence of such a radio telescope would prohibit any visits, robotic or human, that might interfere with its sensitive measurements. And while this is a thought experiment, it won’t be for long. The ability to erect such a telescope is within the reach not just of governments but also some of the private companies developing lunar transportation services.

With geopolitical prestige deeply intertwined with space exploration—and the possibility that geopolitical power might hinge on space success—any such effort to occupy this valuable real estate will be looked upon with skepticism.

The authors, referencing everything from Japan’s insistence that its whale hunting is for scientific purposes (an international tribunal ruled otherwise) to the 1848 California gold rush, worry that the moon could become “an ungoverned space where the mighty and quick prevail at the expense of the weak and slow.”

Their hope, however, is that international actors will fear instability even as they seek advantage. This may lead them to find common standards to ensure that the costs of scientific exploration—in this case, effectively claiming prime real estate—be proportional to their results, offering “a basis for the articulation of grievances against those who conduct their scientific activities as a pretext to occupy valuable lunar features.”

If a lunar Festivus seems far-fetched, just remember that wherever humans go, they have brought their political problems with them. And should the moon become a site of controversy and disagreement, that will serve as an indicator of how successful current efforts to the return to the moon have been.

“If we end up in a position where we are having disputes over who owns what part of the moon according to the Outer Space Treaty, NASA and others have done something very good,” NASA administrator James Bridenstine told Quartz in December 2018.