US hospitals are now required by law to post prices online. Good luck finding them

Thanks to new US law, we now know the standard price for a cotton ball at the New York Presbyterian Hospital is $1.15. The list price for a skull X-ray at Orlando Health is $695 and NYU Langone’s average charge for a heart transplant is $1,698,831.13.

Thanks to new US law, we now know the standard price for a cotton ball at the New York Presbyterian Hospital is $1.15. The list price for a skull X-ray at Orlando Health is $695 and NYU Langone’s average charge for a heart transplant is $1,698,831.13.

Under the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ price-transparency law that took effect on Jan. 1, all hospitals operating in the US are required “to make public a list of their standard charges via the Internet in a machine readable format, and to update this information at least annually, or more often as appropriate.” The landmark legislation expands on a previous requirement that required hospitals to present their standard price lists, or “chargemaster,” upon request.

The new requirement is intended to address the country’s notoriously complex and shadowy healthcare-billing practices, explains CMS administrator Seema Verma. Being able to access a menu of prices will, in theory, allow patients to compare prices across health institutions, which is something Americans haven’t been able to do without a lot of time and effort.

“If patients don’t know the cost of care and can’t compare prices across providers they cannot seek out the highest quality services at the lowest cost, as they do in any other industry,” Verma explained at a Jan. 10 press briefing. She noted that it’s not unusual to see a 50% to 70% price discrepancy for health services between two providers within the same region. “Unlocking price information is essential to enabling patients to become active consumers.”

“If you’re buying a car or pretty much anything else, you’re able to do some research,” Verma explained in an interview with HealthITAnalytics last year. “You’re able to know what the quality is. You’re able to make comparisons. Why shouldn’t we be able to do that in healthcare? Every healthcare consumer wants that.” Following Verma’s logic, uninsured residents of San Antonio, Texas can now decide whether to get a flu shot from Baptist Medical Center for $53.70 or Methodist Hospital for $86.67.

It turns out, it’s not that simple.

The agony of finding the price list

The spirit behind the US government’s push for price transparency is commendable, but the ambiguity of the actual law foils its best intentions.

For one, because CMS vaguely requires that standard prices be published “on the internet,” they are often very difficult to find. Quartz surveyed the websites of 115 of the largest US hospitals, which together account for 20% of all Medicare and Medicaid funding to hospitals. After spending an inordinate amount of time clicking through pages, we eventually found the lists of 105 hospitals. (Direct links to all of these can be found at the bottom of this article.)

In addition, we were eventually able to track down the price lists for six hospitals who hadn’t seemed to make them directly accessible from links on their website by using Google. In general, performing a Google search often provided a shortcut to the rates, but not always. CMS gives hospitals total leeway on the format and the categorization of the lists. We searched for the name of each hospital, along with the terms “price list,” “standard charges,” “standard prices,” and/or “chargemaster” (as well as using the alternative spellings/phrasings “charge master” or “charge description master”).

We called or emailed the remaining four to ask where their lists were. Going through the phone trunkline or public mailbox resulted in excruciating wait times and no definitive answers. We got the quickest response by contacting the hospitals’ media departments—a service not available to most consumers. An agent at the billing department at the University of Minnesota Medical Center initially told Quartz a price list wasn’t posted on the website, and offered a custom quote instead. After publication, Eric Schubert, Director of Communications and Public Engagement for Fairview Health Services, which operates UMMC, contacted Quartz and directed us to its price list. The three others—Hackensack University Medical Center in New Jersey, Lehigh Valley Hospital in Pennsylvania, and Washington Hospital Center in DC, did not reply to inquiries as of writing.

Even among those hospitals that are technically compliant with the new rule, the vast majority don’t make it especially easy for the average person to find their pricing information. We found that most price lists are buried under many sub-menus or at the very bottom of a long page scroll. Nearly 75% of hospital websites in our study required three or more clicks to find the information.

But some lists require hundreds of clicks to find a particular item. Kentucky’s Norton Hospital price index has 1,560 pages, with three separate pages dedicated to “treatment rooms.”

In many instances, the price list is published on illogical pages. Most hospital sites have a “billing” section, but, for example, the Methodist Hospital in San Antonio decided to put its standard rates on the legal page while Indiana University Health has placed it under the Frequently Asked Questions section of its website. Baptist Hospital in Miami published their chargemaster as fine print. Using small, nearly illegible type on websites is particularly dubious because there is no real reason not to use easily readable formatting, giving there are no space limitations (unlike print publications, for example)—especially when the information is meant for people who need medical care. There are often additional barriers. At least five hospitals required the user’s email, and sometimes name, in order to access the data.

Most of these tactics can be categorized as inadequate user experience (UX) design practices. While good UX seeks to improve someone’s experience, poor UX, sometimes called “dark UX,” can misdirect, frustrate, or confuse users. Though it’s impossible to say whether the dark UX in these cases was intentional or not, “the intention of the business is pretty well-reflected on its website,” explains Khoi Vinh, Adobe principal designer and host of Wireframe, an illuminating podcast that tackles usability matters. “Generally, if a business wants something to be found, they’ll make sure it’s easily findable. The more clicks required, the less likely that people will go through them.” Upon reviewing some websites included in our survey, Vinh suggested that some hospitals may not want the information to be found or, perhaps, they didn’t consider the information important enough to highlight.

Unless you’re a machine, good luck reading the prices

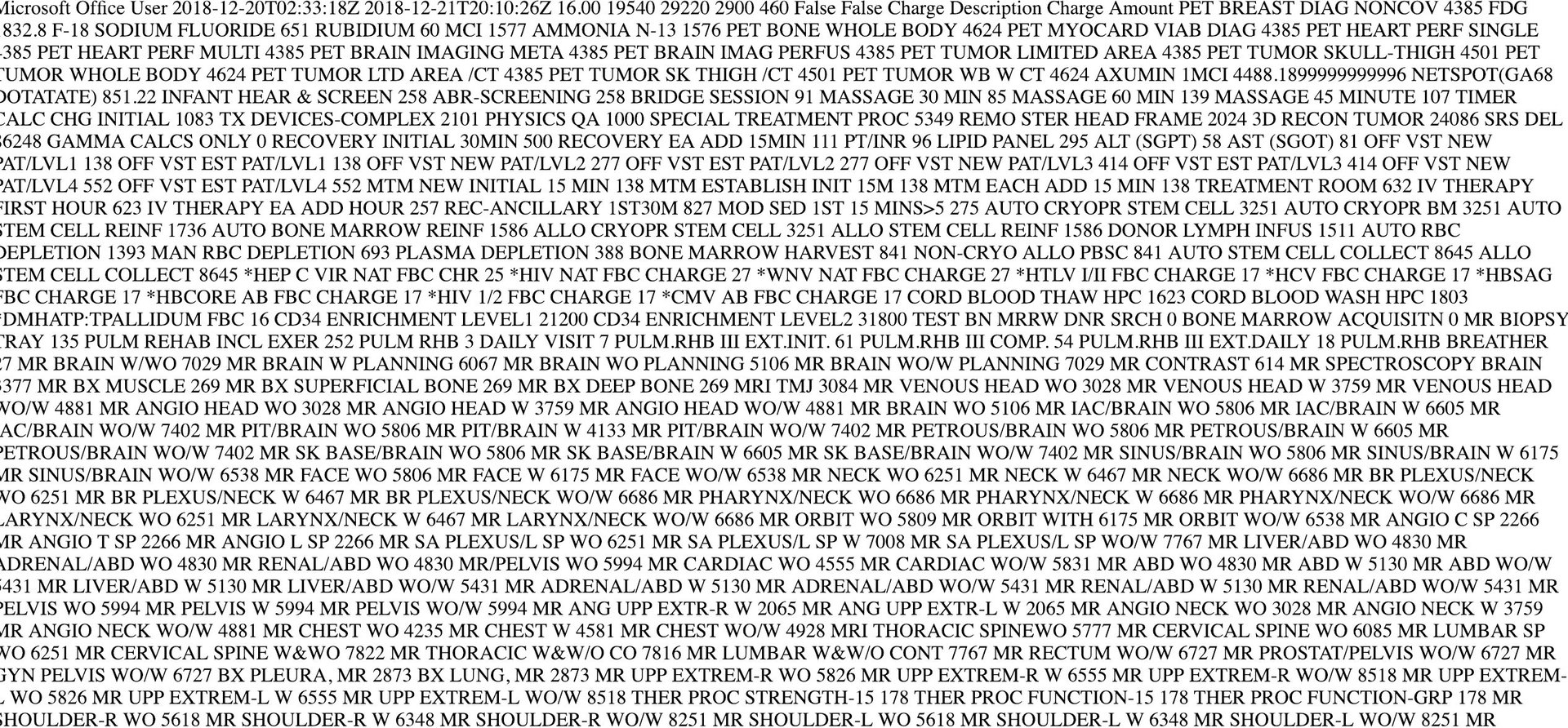

After locating the list, there’s the matter of understanding it. To comply with the law, many hospitals published their entire chargemaster, a list that contains thousands of items—from a cotton ball to an organ transplant—written in terms and codes unintelligible to most consumers. A chargemaster is essentially an internal document that hospitals send insurance companies to negotiate the amount they’re going to receive. The prices listed are typically higher than what most patients actually see on their medical bills, unless they’re uninsured.

The majority of hospital administrators say that CMS’s new law actually makes things more confusing for consumers. Jenni Alvey, senior vice president and chief financial officer of Indiana University Health argues that putting the price transparency burden on hospitals is misguided. “This data is not as useful to patients as it can be in understanding their healthcare costs,” she says. “To further help patients, the Medicare requirements should involve health insurance companies so that they also have a role in price transparency efforts for consumers,” she says in a statement emailed to Quartz.

A spokesperson for Baycare Hospitals echoes Alvey’s concerns: “We much prefer that folks call us or use the online estimator tool. That way, our team is able to talk to them about their specific circumstance and specific insurance.” she says. “Unfortunately, in the US healthcare system, everybody pays something different [even for the same procedure].”

Another problem is the format of the price lists.

The law calls for the data to be published in “a machine readable format” that can be easily imported and aggregated. Reader-friendly PDFs, for instance are not compliant, but Excel spreadsheets and, even worse, markup languages like XML, are. Despite what Verma, the CMS administrator, says about the goal of increasing patients’ ability to make patient-oriented price comparisons, the raw pricing data is meant for algorithms, not humans. In the Jan. 10 press briefing, Velma expressed hope that third-party companies might get involved to help translate the data in consumer-friendly formats.

“I’ve been following this, and I’m completely shocked,” says Emily Ryan, a Washington, DC-based UX advocate. “In some ways this is actually harmful to patients because you’re now giving them false information. In this age of fake news, we have to be very careful as UX and content stewards on what we put out there.” She says that false expectations about pricing can even compromise a hospital’s credibility. “Once we lose trust, it’s very hard to get it back.”

“[Healthcare] is one of the most sacred areas we design in and we have to be very careful,” says Ryan. She adds that any efforts to improve transparency goes beyond publishing prices. It must also include translating the medical jargon to plain, user-friendly language.

CMS needs a UX design bootcamp

Perhaps the most vexing aspects of the hospital-price transparency law is that there are no penalties for non-compliance. CMS also has no mechanism to monitor how and if every US hospital has published their rates. CMS says they’re soliciting ideas from the public on how to enforce the law. Verma declined to comment to Quartz’s query about the timeline on when this might happen.

With any luck, CMS will invite a UX design expert on its advisory panels. Clearer empathy for how users parse information will strengthen agency-wide efforts to promote transparency in prices and quality of care.

“There are many, many interesting opportunities for design to improve the scenario,” suggests Vinh.” The fact that data is being made available, potentially someone can come along and create a meta price index that’s truly usable,” he says. (Start-up idea!)

“It’s crazy that we have this enormous healthcare system, and it’s so complex and you’re expected to negotiate it on your own with no help,” says Vinh.

This article has been updated with additional information from the University of Minnesota Medical Center.