This parenting trick could help curb your kid’s tech addiction

When my daughter was a preschooler in 2011, her request for technology was a simple choice between a talking cartoon dog or a Teletubbies video. But modern parenting has taken a wild turn. Games now come with complicated storylines and mysterious characters, and social media apps come with unknown risks and long-term consequences. Parents unknowingly became sole gatekeepers to this technology fortress—but that doesn’t stop our kids from finding ways across the moat.

When my daughter was a preschooler in 2011, her request for technology was a simple choice between a talking cartoon dog or a Teletubbies video. But modern parenting has taken a wild turn. Games now come with complicated storylines and mysterious characters, and social media apps come with unknown risks and long-term consequences. Parents unknowingly became sole gatekeepers to this technology fortress—but that doesn’t stop our kids from finding ways across the moat.

As a mom raising a Gen Z’er, part of my job is to set boundaries and teach her how to balance the addicting and constantly evolving virtual world with the real one. With an iPhone in hand and access to so many gaming and social networking apps, her desire to be online all the time is a challenge.

Our reality isn’t unique. A May report from the Pew Research Center found that 95% of US teens have a smartphone, and 45% of teens are online on a near-constant basis. (This data is supported by a personal analysis of our car rides, during which she once didn’t notice that I sang the same Fleetwood Mac song 14 times in a row.)

My daughter’s relationship with technology isn’t much different than my own. I spend hours reading an endless stream of Facebook posts while I lie in bed. I watch videos recommended for me, starting with a Jimmy Fallon Late Night clip at 10pm and ending on a heart-wrenching dog reunion video by midnight. After four years working for a tech startup and checking Slack on my phone all hours of the day, I decided to experiment with removing the app. But before I even opened my eyes for the next few days, I found myself mentally searching for the app to check for any messages. People of all ages, myself included, face challenges with creating boundaries for how much time they spend on their phones and the apps on them.

I needed to find a way to help my daughter learn the skills that adults like me were struggling to adopt. So at first, I did as most parents do: I set up parental controls and discussed online safety with her. We set up downtime to disable phone use between 8pm and 8am, app limits of two hours per day, and age-appropriate content and privacy restrictions. Before I did this, I sat down with my daughter and we discussed what we both felt were reasonable limits and changes. This discussion and setting up these foundational agreements helped reduce the number of times we had negative tech-centered interactions throughout the day. It brought peace of mind for the both of us.

Then one evening, my daughter asked to download an app that her friends were using in school. As we agreed, all new app downloads required my consent. Most I allowed because they were within her age rating in the app store, but the requests were becoming more frequent, and the apps were nudging past the pre-approved 9+ age rating: Popular, Hole.io, and Snapchat were just a few.

Normally, I would open up my laptop and start digging into the apps she wanted to download. What’s the age requirement? What’s the content? Who created it? What are people saying about it? How are they making money? Upon completion of my research, I’d make a decision, and my answer would get one of two responses: “cool,” or 200 more questions. I raised my daughter to be strong, vocal, and question everything—I never really thought about what I would do if it was my decision that was being questioned.

In that moment, I remembered that she’d just pulled together a 10-slide deck for my friend outlining why she would be the most qualified dog sitter to her Spanish waterdog puppy. It included a competitive analysis and a closing slide explaining her competitive advantage over an adult: her ability to fit inside the dog’s crate. She pulled together a Google presentation in one evening, delivered it to her potential client, and got the job.

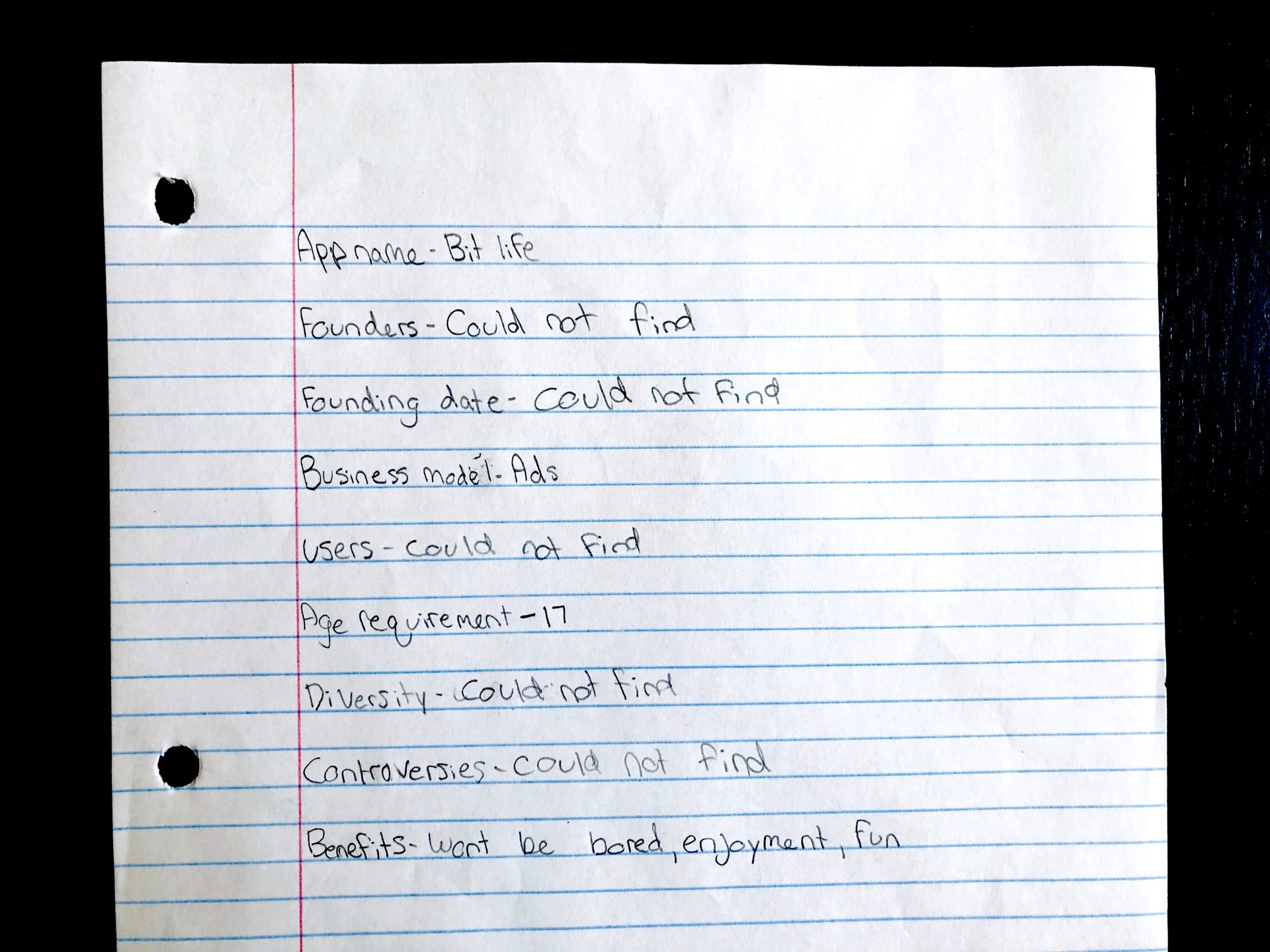

I had an idea. If she wanted to download any new apps, my daughter would take on the task of digging into her own requests. She’d create a mini report that would need to include its founders, investors, background, and how the company benefited from her use. After conducting the research, she could present her findings to me and make a case for the download, just like the puppy sitting.

Her face washed with regret. I could see her eyes counting the number of minutes this would redirect from the time she’d already allocated to Liza Koshy videos. But I could see the wheels turning. She pulled out her laptop and tiredly typed in the name of the app into the search bar, hoping for quick answers and a fast victory.

There were eyerolls and deep sighs when Google would return back little to no information. As a mom does, I rallied for her from the other side of the room. I knew she was both capable and would feel proud when it was complete, as I’ve seen her be many times before. After a few initial difficulties, she asked questions about the best places to find accurate information about founders and investors online.

This wasn’t the first time that we’d researched together. Earlier in the year, we looked up the origins of the favorite foods we consumed; we learned about the connection between beef and deforestation in the Amazon, and decided to reduce our consumption. We looked up how to minimize waste production in order to be active members of a more sustainable community. And we read about how to pull apart the sexism and racism in mainstream media, which influences young people to make false assumptions about how they’re expected to behave or how they should value their peers.

How was researching technology any different? My daughter was also a student of Girls Make Games, where she’s spent several summers learning how to code and design games. She knew how to do this. I encouraged her because I knew she was smart enough—and based on what I saw women deal with in STEM fields in my own career as a woman of color in tech, I may be the only one to ever do it.

The search broadened, and we began to look into other apps, too. She found a dark reality where all of the apps that were successful and popular among her girlfriends were founded by men. In 2018, female-founded startups raised just 2.2% of the $96.7 billion funding pool. When the list of male founder names became too boring to look at, we took breaks to listen to Ariana Grande and recap our hopes for Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Season 3.

By the end of the evening, she put some of her findings together. The brief report for one of the app requests was on one page, and on another she noted that many of the founders of the other apps she uses were men.

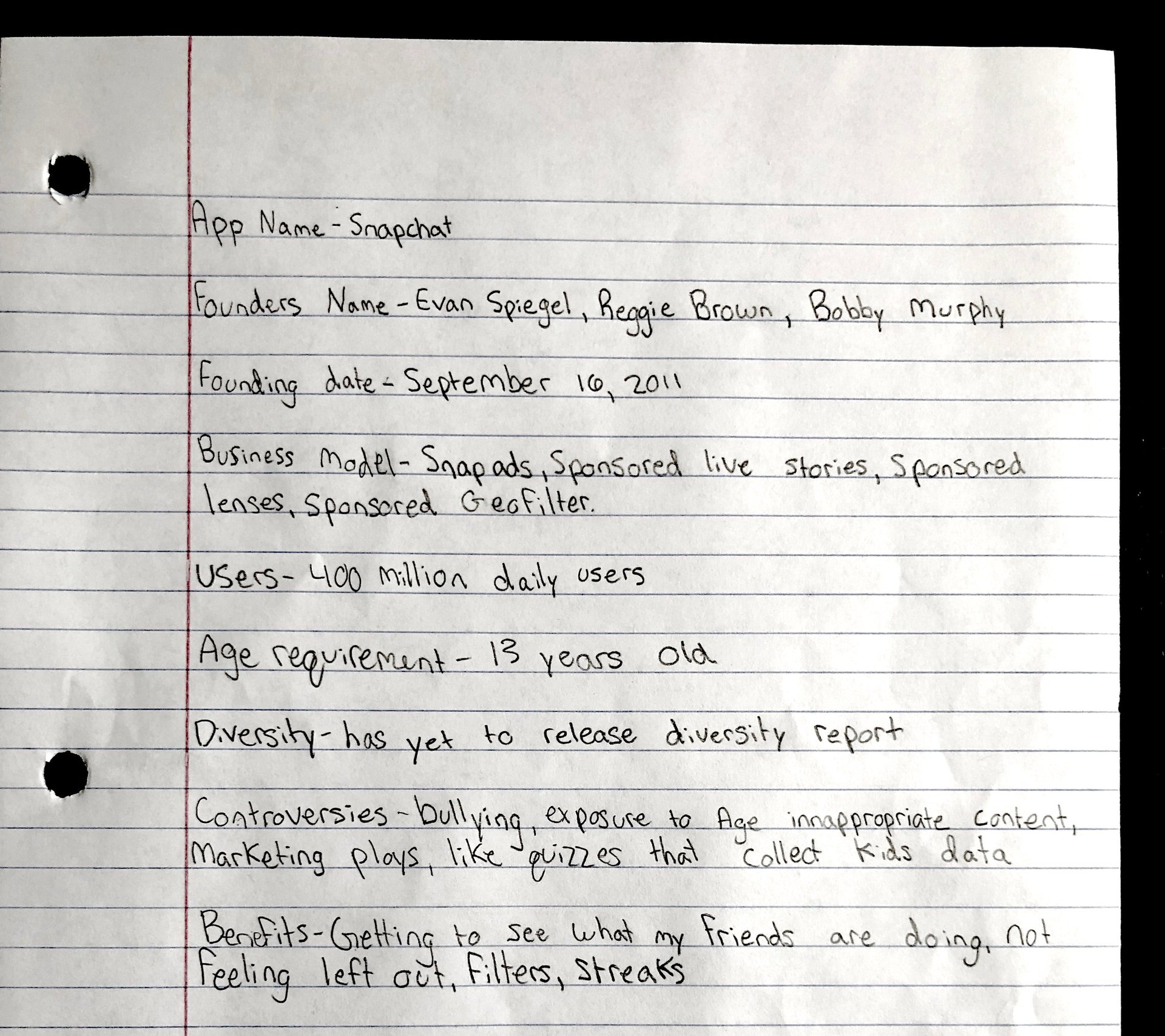

By comparison, here’s one that we created for Snapchat.

This prompted deeper discussion about the mystery behind new apps, as well as who gets to build technology for people like her. She pointed out that up until the iPhone, which made accessing games easier for everyone, boys were introduced to technology through videos games, and their consumption and excitement for it was seen as the norm. Meanwhile, girls—who grow up to become women founders, if they make it—are seen as the exception, not the norm. This is especially true for girls of color, like my daughter, who are underrepresented in this industry.

At the end of her research, my daughter said she was uncomfortable with the mystery behind the app. She decided it was a no—but negotiated whether she could increase the time she spends on apps she feels are “better” than others, such as Headspace or Netflix. I’m proud I’m teaching her to negotiate, even if it means I’m giving up my position as gatekeeper.

It’s tough raising kids in a world where our parental roles are undervalued, and information isn’t as easy to access as we think. I’m not always going to be around when she needs to make a tough decision, and there aren’t enough Ariana Grande songs with answers. I feel it’s my role to teach research and informed decision-making skills to my daughter, to make her conscious and intentional.

I think it’s already working. When the editor of this piece reached out to ask me to write about this experience, I proposed the idea to my daughter. “How do you spell Quartz?” she asked, reaching for her laptop. “I’ll research them for us first.”