What China’s forced military training for students is like

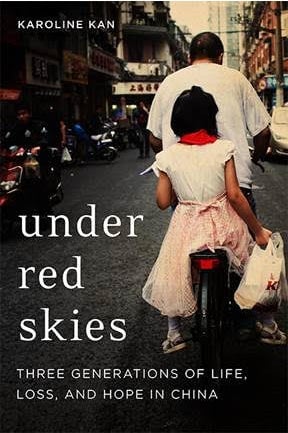

Karoline Kan attempts to weave together a narrative of her generation in her book, Under Red Skies, the first English-language memoir from a Chinese millennial published in the US.

Karoline Kan attempts to weave together a narrative of her generation in her book, Under Red Skies, the first English-language memoir from a Chinese millennial published in the US.

Kan, who was born in 1989 as an illegal second child under China’s one-child policy, says it’s the stories of ordinary Chinese like herself that showcase the real China. Here, she details the experience of junxun, mandatory military training for college freshmen, shortly after starting university in Beijing. Though gruelling, the experience prompted her to learn more about June 4, or the Tiananmen Square protests and massacre, an event that defined the year of her birth that was missing from the history books.

Two weeks after my arrival, [my political counselor-adviser] Guan Xin said I had to start junxun, a form of military training all college freshmen in China must complete. It was supposed to give us a tougher mind-set. Junxun lasted anywhere from two weeks to a month. It had been instated after the Tiananmen Square incident on June 4, when the government sent soldiers to clear people out from the square, during which many students were killed.

Discussion of the June Fourth Incident was prohibited.

[…]

We arrived at what seemed to be the middle of nowhere, in a forest of poplar trees and dark green mountains in the distance, and parked in front of a small compound. Hanging on the front wall was a large red banner: “Welcome, Soldiers from Beijing International Studies University.”

The ceremony started with the raising of the national flag to the music of the national anthem. Our president and the director of the military base gave speeches but I hardly paid attention. My mind was consumed by the twenty or so uniformed men and women who stood beside the stage—I wondered what their roles would be.

We were divided into thirty groups, with men and women separate. I was put in team fourteen, with another forty girls. The jiaoguan, or drill instructors, went around to locate their teams. Our jiaoguan, Liu Lihu, had a round baby face. We were told to address him as “Sir Liu.” He had been a real soldier and had just finished his two years of service…

We got up at 5:30 a.m. and went to bed at 10 p.m. In the morning, we’d run for thirty minutes and then do thirty minutes of junlvquan, or stretching. We were taught to march in military two-steps, moving our legs in unison upon the jiaoguan’s instruction, “one-two-one.” One was left foot, and two was right foot.

We had the same breakfast every day: rice porridge, pickled cabbage, seaweed and peanuts, spicy and salty tofu, and a boiled egg, and had to stand, ten students to a table, to eat. If we weren’t quiet enough while we waited to be served, a jiaoguan could make us squat under the table until the others finished eating. No one was allowed to touch their chopsticks without the jiaoguan’s permission. For lunch and dinner, the formation that marched the most sharply in unison and chanted the patriotic marching songs the loudest was allowed into the canteen first. If our jiaoguan believed we were not trying hard enough, he would delay mealtime… One day a girl standing next to me started scooping more than her share into her own bowl, and it became a full-on scramble. I wasn’t quick enough to get much beyond the only things left: dry and tasteless rice and steamed buns. From that day on, I forgot about being polite.

[…]

I didn’t understand the jiaoguans’ agenda or their rules. We were not soldiers. Yet every morning we had two hours of “military theory lessons” in the canteen. The dining tables were moved to a corner, and we sat on the floor. A wooden desk was put in the middle of the room for guest speakers from the Party School of the Central Committee, who droned on and on in an almost robotic fashion about Chinese military defense systems, wars, and geopolitics. Most of us ended up falling asleep during their lectures.

In the first few days, Sir Liu would yell at the napping students and take them out to stand in the sun as punishment, but soon this stopped being effective. There were too many napping students, and he couldn’t keep interrupting the guest speaker.

Some speakers read the materials plainly and left, but others relished the opportunity to teach us young spoiled kids a real lesson.

Years ago, when politics was thrust upon me in school, I felt a need to respect it enough to try to care. I wanted to know what I should think and desire, and I was grateful to have the government there to tell me. My friends and classmates felt the same, but growing up with a mothering government all your life, there is only one thing to do: grow tired of it. I was not interested in learning how to be a Chinese soldier, and I was growing annoyed with being their student. When you are forced to love something, it loses all its charm.

“Do you know why this class is important?” one speaker, Professor Chen, asked.

Professor Chen looked fiftysomething and had a thin, solemn face. His voice was resonant and deep, and he sat very straight. He was decorated with more medals than any other speaker. “You think the idea of war is far off, don’t you?” He paused for a few seconds. “No! We’re very close to war—more than you think. There is a global bully—called the USA—and don’t you forget it!”

[…]

I was so drowsy I just wanted his speech to end, but he went on. “Corruption is not a product of the socialist system. Russia has a so-called elected president, but corruption is still rampant. India has a democracy, but it’s all chaos. Don’t be naive like those students in 1989 who believed Western democracy would bring about a perfect world.”

Suddenly I perked up, surprised that he mentioned the 1989 incident. Now I wanted him to say more. “Lies!” he said, but didn’t elaborate.

I had heard people refer to the 1989 protest and the June Fourth Tiananmen Massacre; as I mentioned earlier, the protest lasted for more than a month but what makes June Fourth so memorable are the killings.

Although subjects like the Cultural Revolution and the Great Leap Forward were still sensitive, people were relatively eager to talk about them. The 1989 student riot seemed to be the most sensitive story, because my family just shrugged away any questions I had about it.

“You are the generation of 1989,” a family friend once said to me. I wanted him to go on, but he didn’t. “You’ll understand when you get older.”

[…]

But as I’ve grown older, I realize my personal connection with 1989 goes far beyond just the year I was born. Lying in my bunk bed in the Changping military base, I realized that I was no longer a typical Chinese student. I wanted more than to be told when to pee, what to drink, and when to feel that I wanted social change.

This following excerpt was adapted from Karoline Kan’s book Under Red Skies, publishing March 12 from Hachette Books. All rights reserved.