How US trade negotiators are secretly changing intellectual-property law

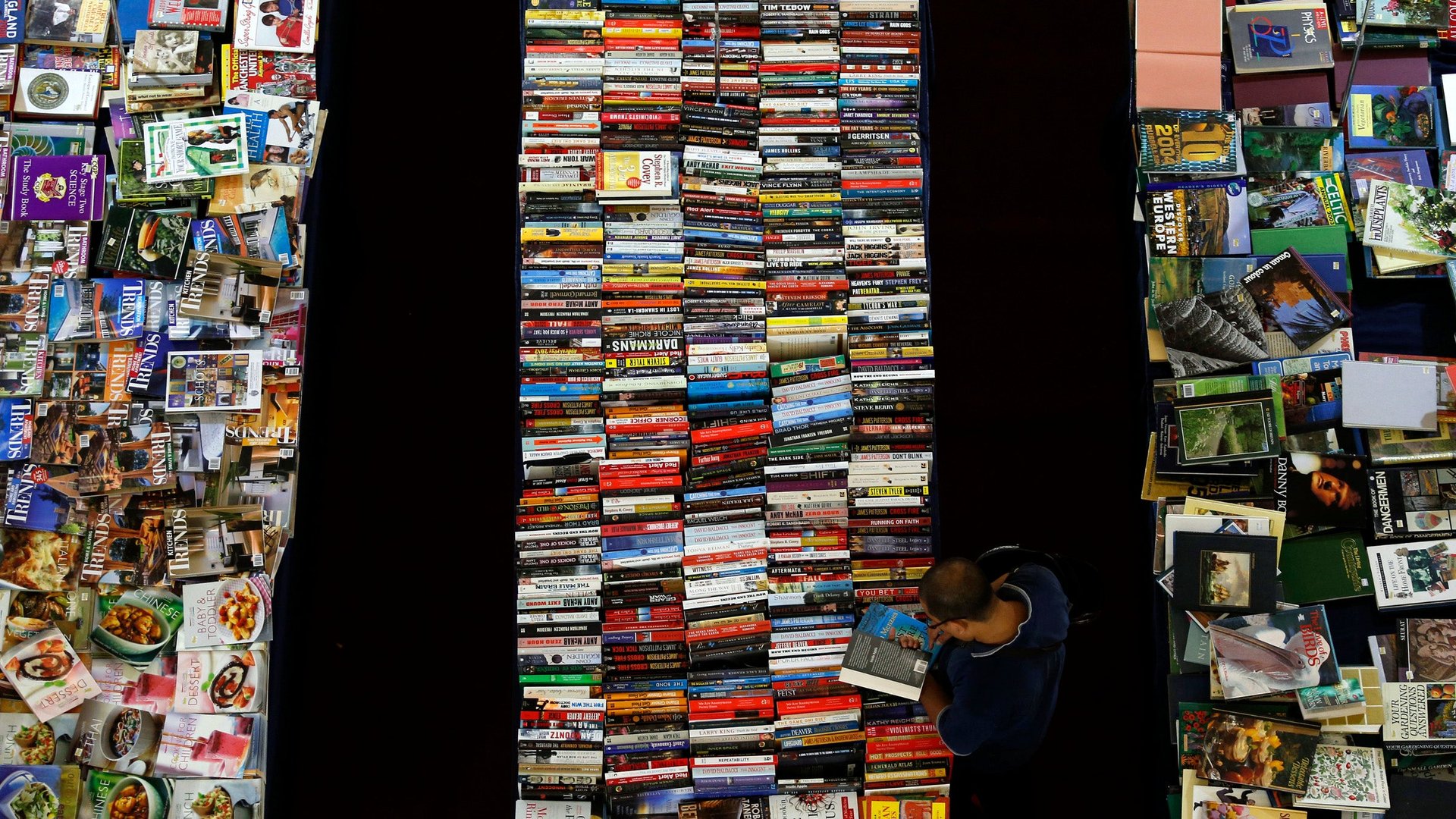

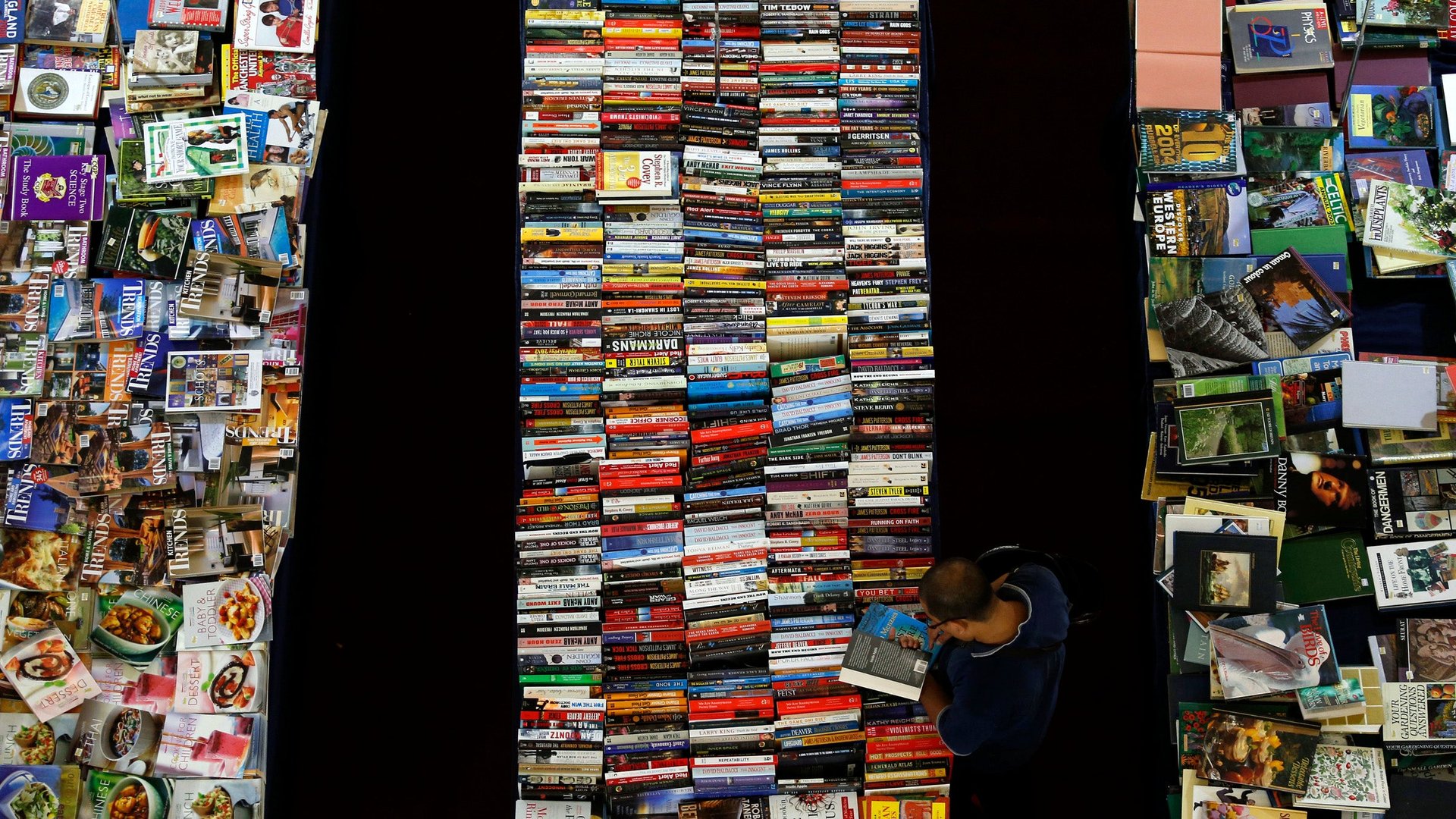

If someone buys a book in Thailand, should she be able to sell it to a used bookstore—or anyone else—in the US? The US Supreme Court says yes. But US trade negotiators say no, and they’re working to make sure the same prohibition would apply around the world.

If someone buys a book in Thailand, should she be able to sell it to a used bookstore—or anyone else—in the US? The US Supreme Court says yes. But US trade negotiators say no, and they’re working to make sure the same prohibition would apply around the world.

Public interest groups have, as we reported last month, criticized a leaked negotiating draft for the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a free-trade deal that would include Japan, Vietnam, and Australia, among others, for exporting US laws they deem overly restrictive. But that draft also shows that US negotiators are adopting positions directly contravening US law.

The supreme court ruled earlier this year in Kirtsaeng v. Wiley that a Thai student legally purchasing textbooks at home could re-sell them in the US because, the court held, the “first sale” doctrine—under which someone who owns a lawful copy of a copyrighted work has the right to sell it—also applies to works made outside the US. Margot Kaminski, a Yale law professor, pointed out in a paper last month that this ruling stands in direct opposition to an existing free-trade deal with Jordan and the position taken by US negotiators in the TPP.

Kaminski argues that trade negotiators have become captured by private sector-advisers and the secrecy around the international deal-making process. Lobbying by business groups is of course commonplace; financial firms and energy companies expend a lot of effort to influence regulators who write the rules that enforce laws. In the case of international intellectual property law, the music and movie industries, among others, push trade negotiators toward positions that will benefit them. But while environmental groups and labor unions are part of official trade advisory groups, there are no public-interest advisors on intellectual property issues.

Advisers to US trade negotiators filed briefs with the Supreme Court opposing the Kirtsaeng decision, and pushed the USTR toward their view, rather than the more balanced language used in the actual statutes. Part of the problem, Kaminski says, is that basic freedom-of-information rules don’t apply to the US Trade Representative and its advisors, keeping the public in the dark and limiting its input. The US Trade Representative declined to comment on the contradiction between the Supreme Court decision and trade negotiations.

Whatever agreement comes out of the TPP will have to be approved by the US Congress, where it will face opposition from information freedom advocates. If they win, negotiators will have to amend the trade deal. But if not, and Congress approves a trade deal that violates domestic law, the US will be vulnerable to trade sanctions—which, Kaminski fears, could lead it to change the law to overturn the Supreme Court decision.

That means more delays and confusion around harmonizing a global approach to intellectual property—exactly what the TPP is supposed to fix.