A Norwegian Air 737 has been stuck in Iran for more than a month

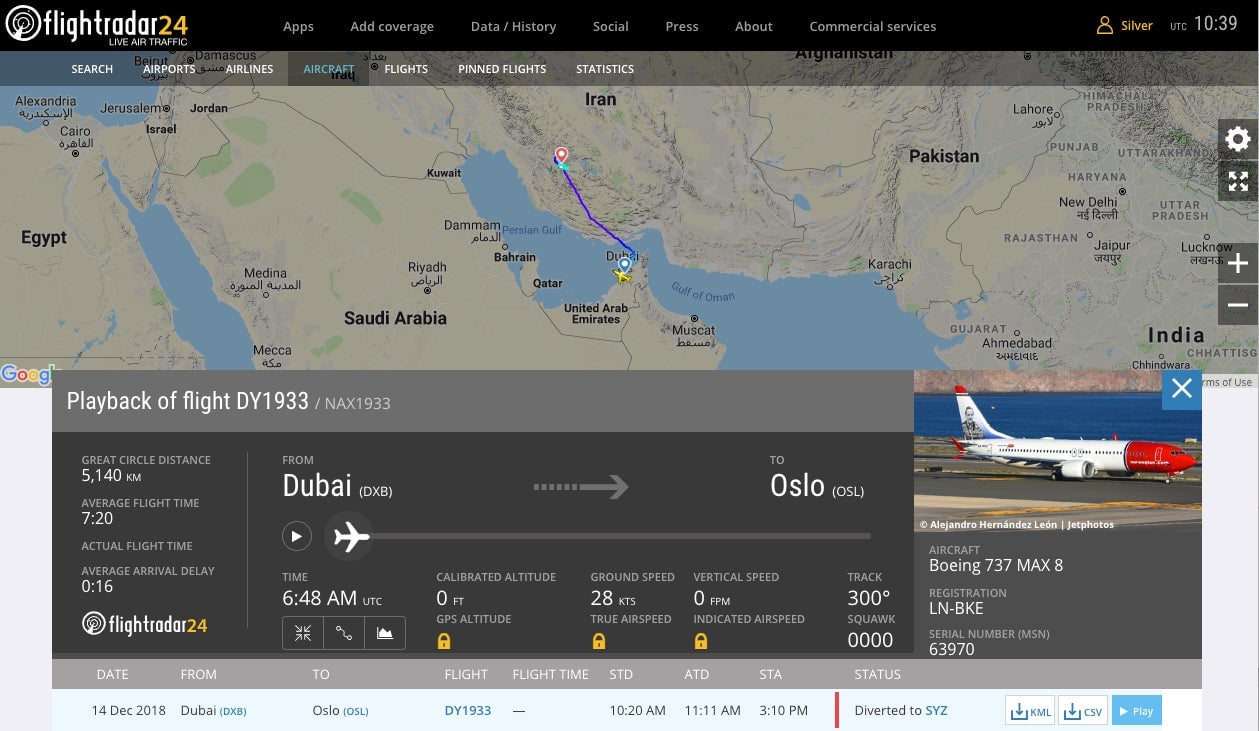

On Dec. 14, technical issues forced a Norwegian Air flight from Dubai to make an unscheduled landing at Shiraz International Airport in the south of Iran. No one was hurt. But the diversion launched a logistical and diplomatic quagmire that has left the aircraft, which had only been in operation for two months, grounded in Iran ever since.

On Dec. 14, technical issues forced a Norwegian Air flight from Dubai to make an unscheduled landing at Shiraz International Airport in the south of Iran. No one was hurt. But the diversion launched a logistical and diplomatic quagmire that has left the aircraft, which had only been in operation for two months, grounded in Iran ever since.

The incident is illustrative of the impact US sanctions on Iran can have on multinational companies. After the passengers and crew on board were transported to their intended destination, Oslo, the next day, the plane needed to be repaired. Its technical issues meant the Boeing 737 MAX 8 aircraft couldn’t fly, even briefly, to an airfield in another country. And like most western airlines, Norwegian Air does not operate out of any airports in Iran, so it needed to import parts from elsewhere.

That has proved difficult.

Economic sanctions imposed by the Trump administration last year place restrictions on Norwegian’s repair job. Any aircraft part needed for the repair that comprises more than 10% components or technology of US origin requires a special license from the US government to import into Iran. (Boeing, which manufactures the 737 MAX, is an American company).

As a lawyer specializing in trade issues told the New York Times (paywall), that license is tough to get—even if there wasn’t a US government shut-down currently ravaging the commercial aviation sector.

A spokesperson for Norwegian Air told Quartz that the company doesn’t have a timeline for when the aircraft might be back in action, adding: “Unfortunately the paperwork necessary to service the plane has taken longer than usual, partly due to fact that we have had to familiarize ourselves with Iranian regulations.”

Separately, US sanctions have also led to a shortage of new aircraft to replace national carrier IranAir’s aging fleet, as Boeing and Airbus are currently prevented by the US Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control from selling aircrafts to Iran.

Norwegian Air has had a tough year when it comes to aircraft shortages, having to previously “wet-lease” several aircraft while its fleet of Boeing 787 Dreamliners, which service its long haul routes, were repaired to fix industry-wide issues with the Rolls Royce-manufactured engine. In perhaps the only silver lining of a tough situation, January is a slow month for commercial aviation, and the company has signaled it can work around the shortages.